Jonas Salk, or Doctor Salk as he became known to millions, was a name synonymous with hope during the terrifying polio epidemics of the mid-20th century. Born on October 28, 1914, in New York City, to Russian-Jewish immigrant parents, Daniel and Dora Salk, Jonas was the first in his family to pursue higher education, a testament to his ambition and intellect. He graduated from the New York University School of Medicine in 1939, embarking on a career dedicated to understanding and combating disease.

Salk’s initial focus was not polio, but influenza. During a research fellowship at the University of Michigan in 1942, and later as assistant professor of epidemiology, he began his journey into vaccine development. Crucially, he reconnected with his mentor, Thomas Francis, Jr., a leading figure in epidemiology at Michigan’s School of Public Health. Francis imparted invaluable knowledge and methodologies in vaccine creation, setting the stage for Salk’s future groundbreaking work.

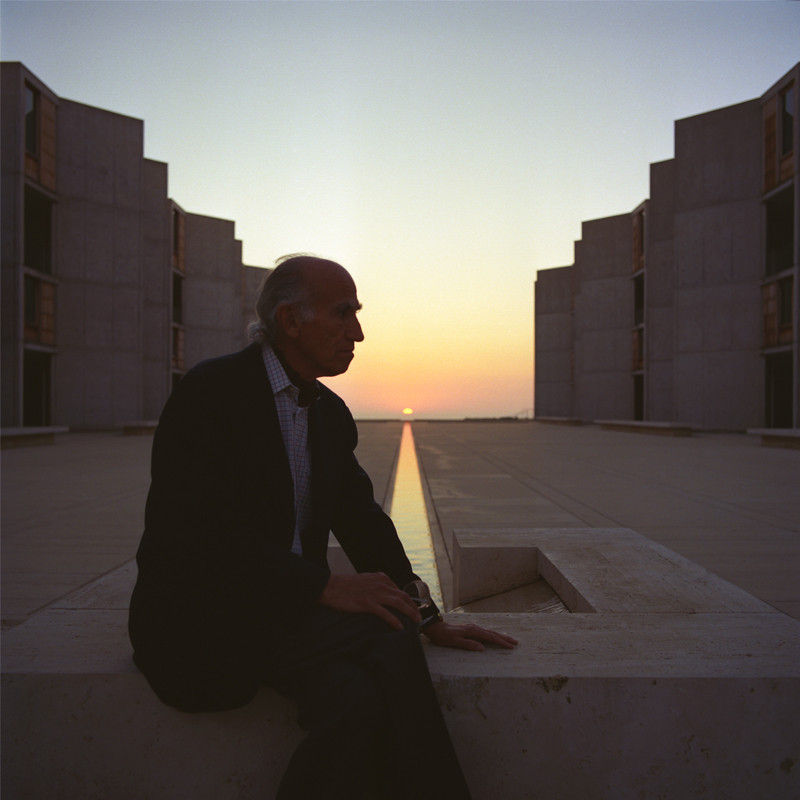

Doctor Jonas Salk in his later years, pictured at the Salk Institute, a renowned biological research center he founded. Salk is celebrated for developing the polio vaccine.

Doctor Jonas Salk in his later years, pictured at the Salk Institute, a renowned biological research center he founded. Salk is celebrated for developing the polio vaccine.

In 1947, Doctor Salk’s career took a pivotal turn when he was appointed director of the Virus Research Laboratory at the University of Pittsburgh School of Medicine. Supported by funding from the National Foundation for Infantile Paralysis (now the March of Dimes), he set his sights on a seemingly insurmountable challenge: poliomyelitis. Polio was a devastating disease, particularly for children, causing paralysis and even death, and fear of outbreaks gripped communities worldwide.

Against prevailing scientific thought, Doctor Salk championed the use of a “killed” polio virus vaccine. The accepted wisdom favored live, attenuated viruses, but Salk believed a deactivated virus could safely trigger immunity without the risk of infection. To prove his theory, he took a bold step, administering his experimental vaccine to volunteers, including himself, his family, and his research team. The results were overwhelmingly positive: all developed polio antibodies with no adverse reactions, demonstrating the vaccine’s potential safety and efficacy.

The year 1954 marked a historic undertaking: a massive national field trial involving over a million children, known as the Polio Pioneers. The nation held its breath, and on April 12, 1955, the announcement came – Doctor Salk’s polio vaccine was safe and effective. The impact was immediate and transformative. In the years preceding widespread vaccination, the United States averaged over 45,000 polio cases annually. By 1962, this number plummeted to just 910. Doctor Salk was hailed as a hero, a medical miracle worker who had liberated a generation from fear.

Remarkably, Doctor Salk never patented his polio vaccine. He believed it was a gift to humanity and should be accessible to all, foregoing personal financial gain for the greater good of public health. This selfless act further cemented his legacy as not just a brilliant scientist, but a deeply humanitarian figure.

Doctor Salk’s contributions extended beyond the polio vaccine. In 1963, he founded the Salk Institute for Biological Studies in La Jolla, California, a world-renowned research institution born from his vision and supported by a substantial grant from the National Science Foundation and the March of Dimes. The Salk Institute became a beacon of scientific discovery, attracting leading researchers from diverse fields.

In his later years, Doctor Salk dedicated his efforts to another global health crisis: AIDS, tirelessly seeking a vaccine until his death on June 23, 1995, at the age of 80 in La Jolla. His enduring philosophy, immortalized at the Salk Institute, serves as an inspiration to scientists and dreamers alike: “Hope lies in dreams, in imagination and in the courage of those who dare to make dreams into reality.” Doctor Salk’s life and work remain a powerful testament to the transformative impact of scientific dedication and human compassion.