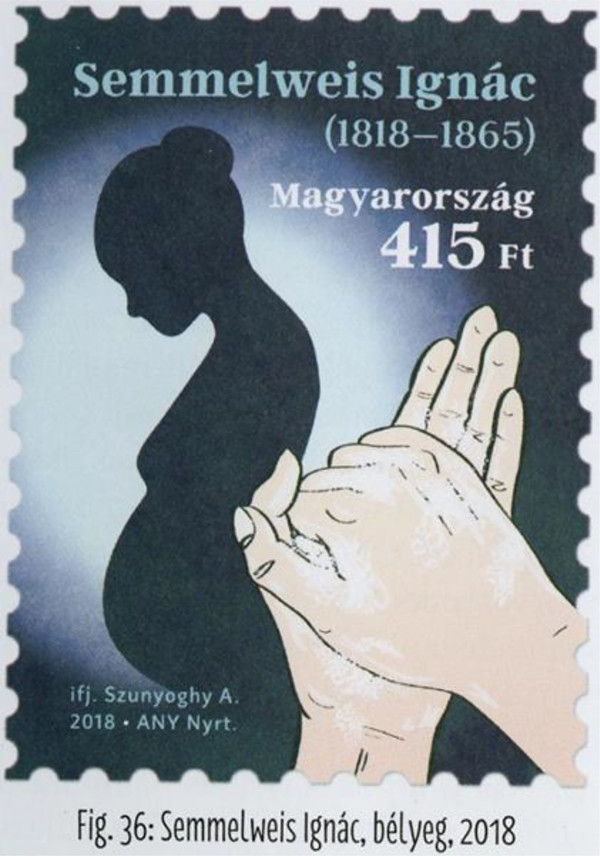

Semmelweis University and the Hungarian Medical Weekly commemorated the bicentennial of Ignaz Philip Semmelweis’s birth (1818–1865) in Budapest, celebrating the life and groundbreaking contributions of a physician who revolutionized medical practice. The 2018 event on June 30th included the minting of a commemorative coin bearing Semmelweis’s profile and an image of handwashing (FIGURE 1), the issue of a commemorative stamp (FIGURE 2), the publication of a biography (FIGURE 3)1, and the unveiling of a sculpture in his honor (FIGURE 4). The global medical community, including publications like the American Journal of Obstetrics & Gynecology, joined in recognizing Doctor Ignaz Semmelweis, a pivotal figure in the history of medicine and a true champion for maternal health.

Honoring Semmelweis: A Bicentennial Celebration in Budapest

The bicentennial celebration underscored the enduring impact of Doctor Ignaz Semmelweis. The commemorative coin, designed by industrial artist Gábor Kereszthury and minted by the Hungarian National Bank, serves as a lasting symbol of Semmelweis’s legacy. One side features his profile, a dignified representation of the man, while the other depicts two hands being washed, a clear visual reminder of his life-saving discovery. This coin, minted in 2018, encapsulates the core of Semmelweis’s contribution to medicine: the simple yet profound act of hand disinfection.

Figure 1. Commemorative coin featuring Semmelweis’ profile and hand disinfection.

Similarly, the Hungarian Post issued a commemorative stamp, designed by graphic artist András Szunyoghy Jr., on June 30, 2018, at Semmelweis University. This stamp further disseminated the recognition of Doctor Ignaz Semmelweis to a wider audience, embedding his image and story into the national consciousness.

Figure 2

Figure 2

Figure 2. Commemorative Semmelweis stamp.

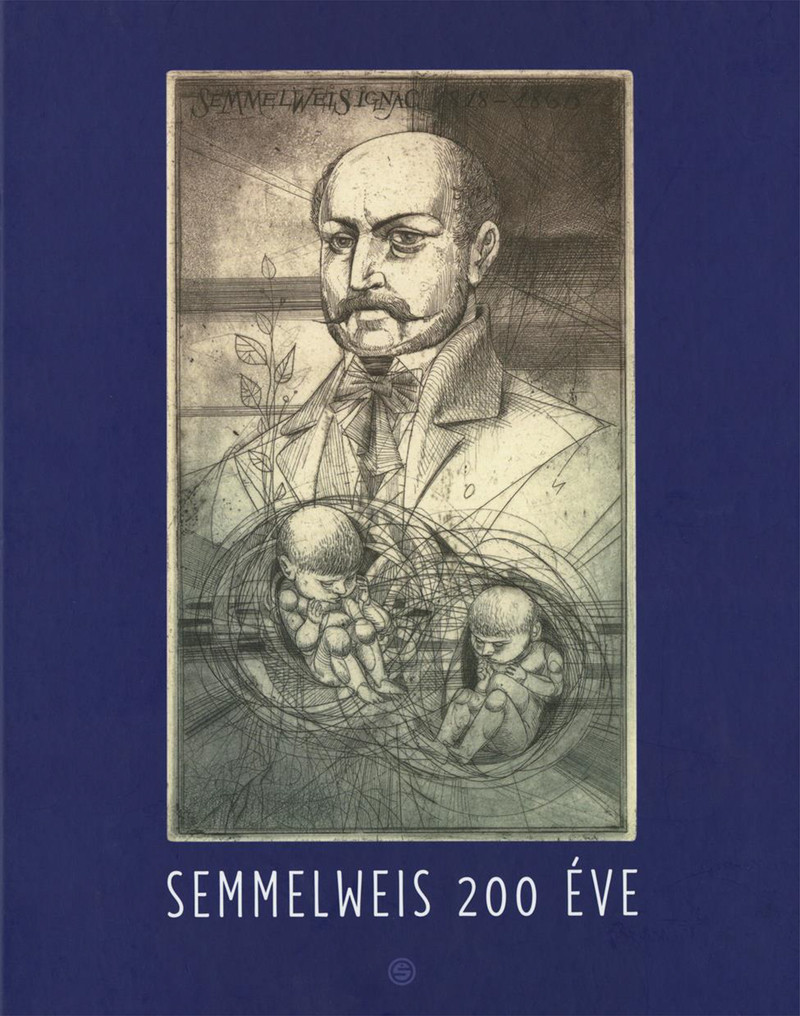

A newly published book, edited by Dr. László Rosivall and released by the Semmelweis University Publishing House, delves into the life and work of Doctor Ignaz Semmelweis, offering a comprehensive account of his struggles and triumphs. This biography serves as an important resource for those seeking to understand the depth of Semmelweis’s contributions and the context in which he worked.

Figure 3

Figure 3

Figure 3. Book celebrating Semmelweis’ life and the 200th anniversary of his birth.

The unveiling of István Madarassy’s sculpture, “In Blessed Condition – Visitation Memory of Semmelweis,” provided a poignant and artistic tribute. Based on a medieval painting depicting the meeting of St. Mary and St. Elizabeth, the sculpture is displayed in the Hall of the Second Department of Obstetrics and Gynecology at Semmelweis University. This artwork serves as a constant reminder within the medical institution of Semmelweis’s dedication to maternal well-being.

Figure 4

Figure 4

Figure 4. In Blessed Condition – Visitation Memory of Semmelweis.

Ignaz Semmelweis: Unraveling the Mystery of Childbed Fever

Born in Budapest on July 1, 1818, Ignaz Semmelweis initially pursued law before switching to medicine, graduating as a physician from the University of Vienna in 1844. His early life in a German-speaking merchant community and education in Catholic schools laid the foundation for a man who would challenge established medical norms. However, it was his appointment as First Assistant at the Vienna General Hospital in 1846 that set the stage for his groundbreaking discovery.

At the time, childbed fever, or puerperal fever, was a scourge of maternity clinics across Europe. Mortality rates were alarmingly high, often exceeding 10%. In the First Division of the Vienna Maternity Clinic, where medical students were trained, the rate hovered around 9%, significantly higher than the 3% in the Second Division, where only midwives practiced. This stark difference, despite numerous investigations, remained unexplained. Doctor Ignaz Semmelweis, witnessing firsthand the devastating impact of childbed fever, became determined to find the cause and prevent further tragedies.

Driven by a relentless pursuit of answers, Semmelweis personally conducted autopsies on women who succumbed to childbed fever. This direct engagement with the disease’s pathology, combined with meticulous observation, proved crucial to his breakthrough. He immersed himself in the hospital’s detailed statistics, which, remarkably, had been collected monthly since 1784, tracking deliveries and childbed fever deaths in both divisions. This wealth of data, essentially a historical randomized study, provided Semmelweis with the raw material for his epidemiological investigation.

The Serendipitous Clue: Jakob Kolletschka’s Death

Semmelweis meticulously examined the differences between the two maternity divisions, systematically eliminating potential causes of the mortality disparity. He considered and discarded various theories, some ascribing the higher rates in the First Division to factors like the supposed embarrassment of women being examined by male physicians. By October 1846, his initial assistantship ended, but upon his reappointment in March 1847, a tragic event provided the pivotal clue.

The death of Jakob Kolletschka, a friend and forensic pathologist, proved to be Semmelweis’s moment of insight. Kolletschka died from sepsis after a student accidentally punctured his finger with a scalpel during an autopsy. Examining Kolletschka’s autopsy report, Doctor Ignaz Semmelweis recognized a striking similarity to the findings in women who died from childbed fever. The only difference was the absence of genital involvement in Kolletschka.

This observation led Semmelweis to a revolutionary inference: if Kolletschka died from a process akin to childbed fever, then the cause of death in mothers must be the same as the cause of Kolletschka’s death. This was a radical departure from prevailing medical thought, which attributed childbed fever to a multitude of factors, some estimating as many as thirty different causes. Semmelweis posited a single, unified cause.

“Cadaveric Particles” and the Birth of Hand Disinfection

Doctor Ignaz Semmelweis concluded that a substance he termed “cadaveric particles” was the culprit. These particles, originating from decaying organic matter from cadavers, were introduced into Kolletschka’s bloodstream via the scalpel wound. Similarly, he reasoned, these particles were being transmitted to women during childbirth via the hands of doctors and medical students who performed autopsies and then examined patients in the First Division. Handwashing with soap and water, the common practice at the time, was insufficient to remove these infectious agents, as evidenced by the persistent odor on the hands after washing.

The crucial difference between the two divisions became clear: medical students and physicians in the First Division were involved in autopsies, while midwives in the Second Division were not. This meant that patients in the First Division were far more likely to be examined by individuals whose hands were contaminated with “cadaveric particles.” Semmelweis had solved the mystery.

Chlorine Handwashing: A Dramatic Reduction in Mortality

Driven by his discovery, Doctor Ignaz Semmelweis sought a more effective method of hand disinfection. After experimenting with various solutions, he found that a chlorine solution was most effective in removing the lingering odor associated with cadaveric matter. In May 1847, he persuaded his chief to implement mandatory chlorine handwashing for all personnel before entering the labor ward in the First Division. Once inside, staff could use soap and water between patient examinations, but chlorine disinfection was required upon entry.

The results were nothing short of dramatic. In the three months following the introduction of chlorine handwashing (June to August 1847), the maternal mortality rate in the First Division plummeted from 7.8% to a mere 1.8%. However, this initial success was followed by a concerning spike in October and November, with mortality rates rising again.

Undeterred, Semmelweis investigated these resurgences. He traced the October spike to a patient with a purulent uterine carcinoma. This led him to refine his protocol, mandating chlorine handwashing not only upon entering the ward but also between each patient examination. The November spike was linked to a patient with a purulent knee infection. From these cases, Semmelweis realized that any source of “decaying animal organic matter,” not just cadavers, could transmit infection. He also recognized a small percentage of cases, about 1%, he termed “autoinfection,” arising from birth trauma or retained placenta, which were not preventable by handwashing.

By 1848, with his refined handwashing protocols fully implemented, the maternal mortality rate in the First Division fell to an astonishing 1.27%, even lower than the rate in the midwives-led Second Division (1.33%). Doctor Ignaz Semmelweis had proven the efficacy of his hand disinfection method.

Resistance and Gradual Acceptance

Despite the compelling results, Semmelweis’s findings were initially met with skepticism and resistance from the medical establishment. His preliminary results were published in editorials in the Journal of the Medical Society of Vienna in December 1847 and April 1848, inviting confirmation or refutation from European maternity clinics. Semmelweis and his colleagues also sent letters to prominent obstetricians across Europe. However, the responses were largely negative.

Objections were raised on various grounds, and numerous reasons were subsequently offered for rejecting Semmelweis’s doctrine. However, the primary obstacle was the paradigm shift his theory demanded. Accepting Semmelweis’s idea meant acknowledging that a disease like childbed fever could have a single, preventable cause – external contamination. This was a radical departure from the prevailing miasma theory and complex causal models of disease. The medical world was not yet ready to embrace the concept of invisible infectious agents. Widespread acceptance would have to wait for the development of the Germ Theory of Disease and the eventual understanding of bacteria as the true culprits of infection.

Return to Budapest and Continued Advocacy

Semmelweis’s contract in Vienna was not renewed, and facing professional limitations, he returned to Budapest in 1850. Hungary was in a period of political turmoil following its defeat in the war of independence against Austria. Despite the challenging environment, Semmelweis accepted an unpaid position as Head of Obstetrics and Gynecology at St. Rókus Hospital.

During his six years at St. Rókus Hospital (1851–1857), Doctor Ignaz Semmelweis replicated his success. The overall maternal mortality rate from childbed fever at the hospital was a remarkable 0.85%, in stark contrast to the 10% to 15% rates prevailing in Prague and Vienna during the same period. His consistent results further validated his handwashing doctrine.

In 1855, Semmelweis was appointed Professor of Theoretical and Practical Midwifery at the University of Pest. He succeeded Professor Birly, a staunch opponent of handwashing who believed childbed fever originated in the bowel and advocated for purgatives. The University’s Maternal Clinic was in poor condition, and childbed fever was rampant. Semmelweis faced constant administrative battles for basic necessities like clean linens. Nevertheless, he persevered and successfully relocated the clinic to a new facility. Despite the challenges, Semmelweis reduced maternal mortality from childbed fever to 0.39% in his first year as professor, and maintained a rate below 1% in subsequent years.

Publication of “The Etiology, Concept and Prophylaxis of Childbed Fever”

Thanks to the encouragement of Lajos Markusovszky, a fellow Hungarian medical icon and founder of Orvosi Hetilap (Hungarian Medical Weekly), Doctor Ignaz Semmelweis finally published his findings on childbed fever in 1857. He further elaborated on his doctrine in subsequent publications, clarifying his views and distinguishing them from the “contagionist” theories prevalent in England. He emphasized his belief that every case of childbed fever, without exception (excluding autoinfection), was caused by decaying animal organic matter.

In 1859, Semmelweis began writing his seminal work, The Etiology, Concept and Prophylaxis of Childbed Fever (Die Ätiologie, der Begriff und die Prophylaxis des Kindbettfiebers), which was published in German in 1860. This book meticulously detailed his research, observations, and conclusions, representing the culmination of years of dedicated work.

Eventual Recognition and Tragic End

Despite sending copies of his book to leading obstetricians across Europe, initial responses remained largely negative. Prominent figures like Rudolf Virchow and Friedrich Scanzoni von Lichtenfels continued to oppose his doctrine, holding onto alternative theories about the causes of childbed fever.

However, over time, Semmelweis’s ideas gradually gained traction. Even those who initially resisted his doctrine began to adopt prophylactic hand disinfection, albeit often without acknowledging Semmelweis’s contribution. By 1864, even Virchow publicly recognized the merit of Semmelweis’s work. Scanzoni, a particularly vehement critic, conceded in the 1867 edition of his textbook that childbed fever was almost unanimously considered an infectious disease and acknowledged Semmelweis’s significant service to lying-in women.

Tragically, Doctor Ignaz Semmelweis did not live to witness the full triumph of his doctrine. He died in an asylum in 1865 at the age of 47. Recent historical evidence suggests his death may have been hastened by injuries sustained during his confinement, leading to sepsis. The underlying cause of his mental health decline remains a subject of debate, but his brilliance, originality, and unwavering commitment to his patients are undeniable. Ignaz Semmelweis’s legacy endures as a testament to the power of observation, perseverance, and the profound impact of a simple yet life-saving practice: hand hygiene.

Acknowledgment:

This work was supported, in part, by the Perinatology Research Branch, Division of Intramural Research, Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development (NICHD), National Institutes of Health (NIH), Department of Health and Human Services (NICHD/NIH); and, in part, with Federal funds from NICHD, NIH under Contract No. HSN275201300006C.

Footnotes

Disclosure: The authors report no conflicts of interest.

Contributor Information

Nicholas Kadar, 11 Jackson Court, Cranbury, NJ.

Roberto Romero, Perinatology Research Branch, Division of Obstetrics and Maternal-Fetal Medicine, Division of Intramural Research, Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development, National Institutes of Health, Bethesda, MD and Detroit, MI; Department of Obstetrics and Gynecology, University of Michigan, Ann Arbor, MI; Department of Epidemiology and Biostatistics, Michigan State University, East Lansing, MI; Center for Molecular Medicine and Genetics, Wayne State University, Detroit, MI.

Zoltán Papp, Department of Obstetrics and Gynecology, Semmelweis University, Budapest, Hungary; Maternity Private Department, Kútvölgyi Clinical Block, Semmelweis University, Budapest, Hungary.

References

[1] Rosivall L, editor. Semmelweis Ignác, az anyák megmentője [Ignaz Semmelweis, the savior of mothers]. Budapest: Semmelweis University Publishing House; 2018.

[2] Carter KC, Selwyn BJ. Childbed fever redux: Semmelweis and Snow. J Hist Med Allied Sci. 1994 Oct;49(4):550-77.

[3] Koch R. Investigations into the etiology of traumatic infective diseases. In: Brock TD, editor. Robert Koch, Essays of Robert Koch. Washington, D.C.: ASM Press; 1987. pp. 65–113. Originally published in German, Leipzig, 1878

[4] Nuland SB. The doctors’ plague: germs, childbed fever, and the strange story of Ignac Semmelweis. New York: W.W. Norton & Company; 2003.

[5] Semmelweis IP. The etiology, concept and prophylaxis of childbed fever. Budapest: Royal University of Hungary; 1952.

[6] Semmelweis IP. Die Aetiologie, der Begriff und die Prophylaxis des Kindbettfiebers. Wien: Verlag von C.A. Zamarski; 1861.

[7] Benedek I, Kapronczay K. Ignaz Philipp Semmelweis (1818-1865). Wien Klin Wochenschr. 2018 Sep;130(17-18):665-670.

[8] Markusovszky L. [The address of the editor]. Orvosi Hetil. 1857;1:3–6. Hungarian.

[9] Scanzoni FV. Lehrbuch der Geburtshilfe. 4th ed. Wien: Verlag von Carl Gerold’s Sohn; 1867.

[10] Best M, Neuhauser D. Ignaz Semmelweis and handwashing: then and now. Qual Saf Health Care. 2004 Oct;13(5):390-1.

[11] Youngs LA. Ignaz Semmelweis: triumph over adversity. ANZJOG. 2005 Dec;45(6):543-6.