During devastating epidemics, particularly the plague outbreaks that ravaged Europe in the Middle Ages, a specialized physician known as a “plague doctor” emerged. These doctors were public health officials contracted by towns and cities to care for plague victims. Their role was crucial in managing outbreaks, offering a glimmer of hope amidst widespread fear and death, even if their methods now seem archaic. These weren’t always highly trained medical professionals in the modern sense; often, they were simply individuals willing to confront the disease when many others, including established doctors, fled.

Plague doctors operated under a contract, often with municipalities, which defined their duties, compensation, and operational boundaries. A key aspect of their contract was the obligation to treat all plague sufferers, regardless of their ability to pay, ensuring care even in the poorest and most afflicted neighborhoods. This commitment set them apart during times when even general physicians were hesitant to treat plague patients due to the high risk of infection. The dire circumstances of plague outbreaks meant that experienced doctors often left, creating a void filled by those with less experience, or sometimes, those with no formal medical training at all, but with a willingness to serve.

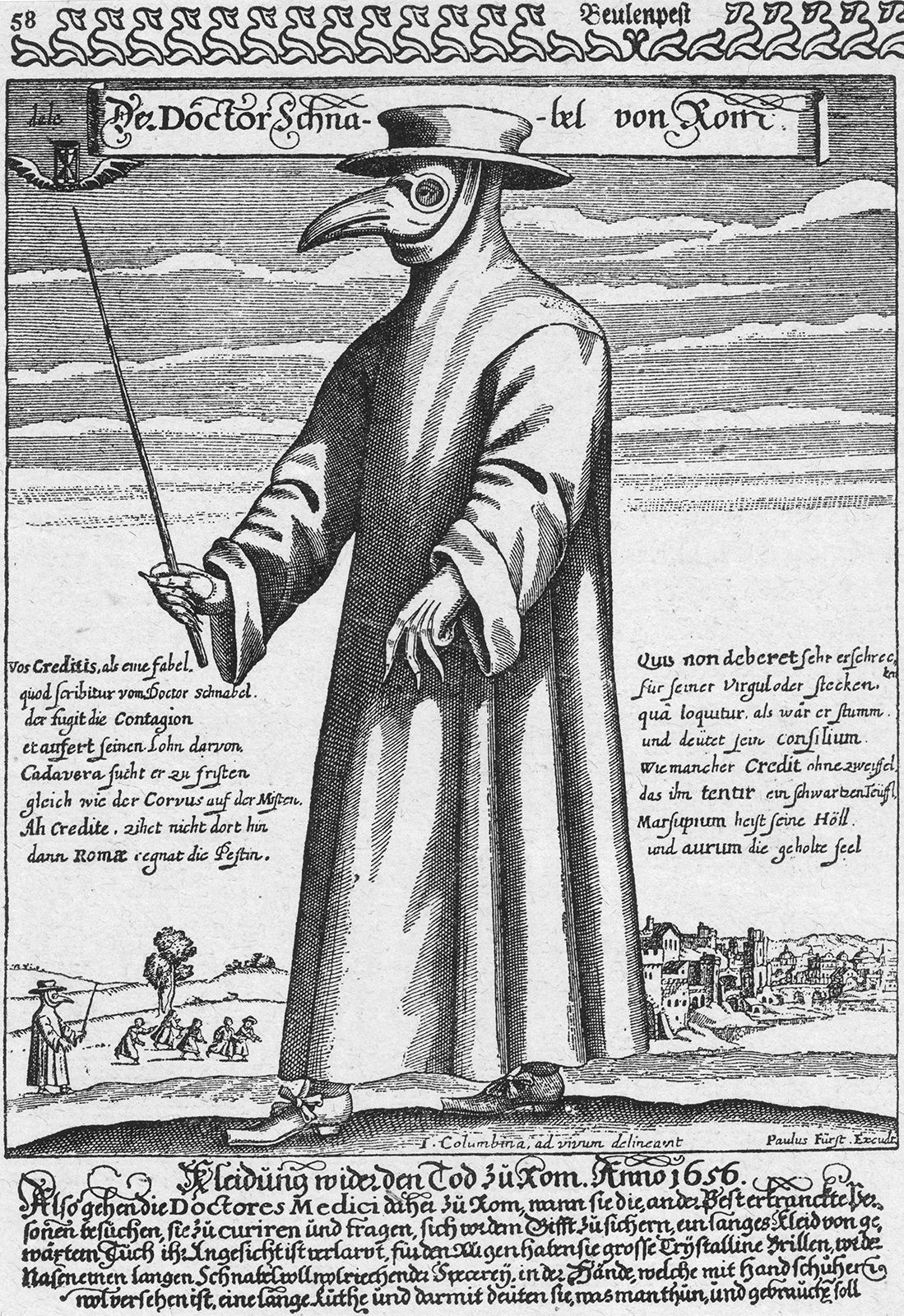

Protective clothing of a plague doctor, circa 1656

Protective clothing of a plague doctor, circa 1656

Beyond treating the sick, plague doctors performed a range of vital public health functions. They meticulously recorded the number of plague cases and fatalities, providing crucial data for understanding the epidemic’s progression. They were often called upon to witness wills, especially for those who feared imminent death, ensuring legal and orderly transitions of property. In some instances, plague doctors conducted autopsies to further understand the disease and its effects on the body, contributing to the limited medical knowledge of the time. Many also kept journals and detailed casebooks, attempting to document observations and treatments, hoping to contribute to the development of more effective future strategies against the plague.

The treatments administered by plague doctors were rooted in the medical understanding of the Middle Ages, which was significantly different from modern medicine. Facing a disease they didn’t fully comprehend, their methods were largely ineffective against the plague itself. Common practices included bloodletting and draining fluids from buboes, the characteristic swellings caused by bubonic plague. They also prescribed medicines intended to induce vomiting or urination, all based on the prevailing theory of balancing the body’s humors – the four bodily fluids believed to influence health and temperament. These treatments, while well-intentioned within the context of contemporary medical science, offered little to no actual benefit to plague victims.

Perhaps the most enduring and recognizable aspect of the plague doctor is their distinctive and somewhat unsettling attire. The iconic plague doctor costume, which became standardized in the 17th century, consisted of a long, ankle-length coat typically waxed for protection, paired with leggings connected to boots, gloves, and a wide-brimmed hat. The most striking feature was the beaked mask. These masks had glass or crystal eyepieces to protect the eyes and a long beak. Plague doctors also carried a wand or staff, used to examine patients and give instructions without making direct contact, maintaining what they believed to be a safe distance from infection. Attributed to Charles de Lorme, a physician to French royalty in the early 17th century, this costume became a symbol of the plague doctor. Ironically, this grim figure and their peculiar outfit became fodder for macabre humor and appeared in caricatures and jokes, turning the plague doctor into a readily identifiable, if unwelcome, symbol of death and disease. The costume’s striking appearance also led to its adoption in theatrical traditions like the Italian commedia dell’arte and as a popular choice for Venetian Carnival costumes, experiencing a modern resurgence during the COVID-19 pandemic.

The beak of the plague doctor mask wasn’t merely for show; it served a purpose based on the miasma theory of disease. This theory, dominant at the time, posited that diseases were spread through foul-smelling air, or “miasma.” To combat this, the beak was filled with aromatic items such as lavender, mint, and other herbs and flowers, or substances like myrrh, camphor, and vinegar-soaked sponges. Some doctors even used theriac, a complex mixture believed to be a universal antidote. While the miasma theory was incorrect, the plague doctor’s costume, in practice, offered a degree of protection. The full-body covering could shield against infected fleas and potentially reduce exposure to bodily fluids and respiratory droplets, offering unintentional protection against the very diseases they were battling.