Introduction

In the demanding world of healthcare, a physician’s time stands as an invaluable asset. How these dedicated professionals allocate their working hours profoundly influences the quality of patient care, the overall cost-effectiveness of healthcare systems, patient experiences, and, crucially, physician well-being, job satisfaction, and the maintenance of professional standards.[1-3] In recent years, the escalating amount of time physicians dedicate to electronic health records (EHRs) has sparked considerable interest and concern about physician time management. Yet, concrete data on precisely how physicians spend their time remains surprisingly limited.[2, 4, 5]

This study embarked on an innovative approach, leveraging ecological momentary assessment (EMA), to gain a detailed understanding of physician time allocation. Beyond just quantifying time, the research aimed to assess the practicality of EMA for broader, large-scale investigations into physician time utilization in the future.[6] Think of it as trying to understand the daily schedule of “Time Doctors” – those who are experts in managing health over time – by observing their activities in real-time.

Methods: Capturing Moments in a Physician’s Day

Ecological Momentary Assessment: A Real-Time Lens

Ecological momentary assessment (EMA) represents a cutting-edge technique increasingly utilized in healthcare research, although its application to the study of physician time has been novel until now.[6, 7] EMA’s strength lies in its ability to capture physicians’ self-reported activities as they happen, minimizing the recall bias inherent in retrospective surveys and avoiding the potential behavioral changes that might occur when physicians are observed directly (as in traditional time-and-motion studies). When EMA protocols employ random sampling and achieve high compliance rates, as seen in this study, the collected data points offer an unbiased snapshot of time use during the monitored period.[6-8]

For this study, we developed and rigorously pilot-tested a user-friendly Android smartphone application. This app served as our “time tracker.” Participating physicians selected days when they would be engaged in outpatient care – days focused on patient consultations rather than surgery, for example – and specified their expected working hours. Throughout these workdays, the app would send random “beeps” at unpredictable intervals. Upon receiving a beep, physicians were prompted to quickly select the activity they were engaged in at that precise moment from a pre-defined list. To ensure timely responses, physicians had an 8-minute window to respond to each beep, with a gentle reminder beep at the 6-minute mark. Missed responses were recorded as unanswered, but compliance was remarkably high (more details in Appendix Sections 1 and 3 of the original paper).

Defining Activities: What Do “Time Doctors” Actually Do?

Drawing upon existing literature and preliminary pilot testing with physicians, we curated a comprehensive list of 14 distinct activities (see Table 1) that physicians commonly undertake during their office hours.

Table 1: A Detailed Look at Physician Work Activities

| Activity | Description | Category |

|---|---|---|

| Interacting with a patient and/or family | Engaging in conversations with patients and/or their families; conducting physical examinations; performing medical procedures | Patient Care |

| Electronic Health Record input | Dictating or directly entering progress notes into patient medical records; coding diagnoses and billing codes; electronically signing records | EHR Input |

| Reviewing/planning | Scrutinizing patient medical records and test results; formulating treatment plans for patients; researching clinical guidelines or relevant medical literature | Patient Care |

| Communication about patients with: | ||

| Patient and/or family | Communicating via phone, email, secure patient portals, or letters, concerning patient care | Patient Care |

| Staff at office, hospital, or nursing home | ||

| Other healthcare providers | ||

| Insurance company, not prior authorization | ||

| Prior authorization | Navigating the process of obtaining prior authorization for medications, tests, procedures, medical devices, referrals, etc. | Administrative Work |

| Pharmacy | Ordering or refilling patient prescriptions. (Note: Time spent on prior authorization should be categorized under “prior authorization”) | Administrative Work |

| Workers’ Compensation | Reviewing patient cases and medical records; preparing required reports | Administrative Work |

| Teaching/supervising | Educating and supervising medical students, residents, or fellows | Teaching/Supervising |

| Administrative tasks/meetings | Attending meetings or undertaking other general administrative duties | Administrative Work |

| Personal time | Breaks for meals, personal phone calls or emails, informal conversations with office staff unrelated to patient care | Personal Time |

| Other | Any work-related activity not encompassed by the provided categories | Other |

List of the 14 activities physicians could select from in the app. Descriptions were concise within the app. Categories were used for analysis.

Interestingly, physicians frequently reported multitasking (32.1% of the time), engaging in two or more activities simultaneously when prompted. To account for this, we expanded our analysis to include combinations of activities (Appendix Table A1 in the original paper). This allowed us to distinguish between time spent on single activities (like “interacting with a patient”) and time spent multitasking (e.g., “interacting with a patient” while also “EHR input”). All activities and activity combinations were then categorized into six broader groups: Patient Care, EHR Input, Administrative Work, Teaching/Supervising, Personal Time, and Other (Appendix Table A1).

A crucial distinction was made in how we categorized EHR-related activities. “EHR Input” was specifically defined as the act of “dictating or entering notes, coding, and signing records.” “Reviewing/Planning,” on the other hand, encompassed “reviewing records, planning care, and researching guidelines.” When EHR Input was reported as the sole activity, it was categorized as EHR Input, not Patient Care. This decision reflects the ongoing concerns about the extensive time spent on EHR documentation, often perceived as burdensome data entry.[3, 9] Conversely, “Reviewing/Planning,” even as a single activity, was classified as Patient Care because it is typically a proactive, clinically driven task, often occurring independently of direct EHR use. However, EHR Input was included within Patient Care when it occurred in combination with other patient-facing activities, such as “Interacting with a patient and/or family + EHR input.”

Participants: A Diverse Group of “Time Doctors”

Using the CarePrecise Physician Database, a national registry, we initially randomly selected 435 physicians across three specialties: orthopedics, non-interventional cardiology, and general internal medicine (excluding hospital-based physicians). We reached out through multiple channels – mail, phone, and email when possible.

Interested physicians completed a brief online survey to confirm their eligibility and provide demographic and practice information. Eligibility criteria included working at least 20 hours per week in patient care and owning an Android phone (or willingness to use a loaner Android phone, as the app was Android-compatible). Participating physicians received a $200 gift card as appreciation.

The initial response rate was low (8.3%, resulting in 10 physicians from 10 practices). To broaden our sample, we recruited an additional 53 physicians, including family medicine practitioners, from a convenience sample of practices. This expanded our study to 18 more practices across the United States. Two physicians were later excluded because they reported spending less than 50% of their beeped time in the office/hospital. The final participant group consisted of 61 physicians from 28 practices in 16 states (Appendix text and Fig. A1 in the original article provide further details). Recruitment and data collection spanned from January 2017 to May 2018.

Data Analysis: Making Sense of Time Allocation

After excluding time spent on “Personal Time,” we analyzed the proportion of work time physicians dedicated to each activity category. This analysis was conducted across the entire physician group, broken down by specialty, and by practice ownership model. We also identified the most frequent sub-activities within each category. These proportions were calculated by dividing the number of beeps for each activity category by the total number of beeps, excluding personal time beeps. Statistical differences between groups were assessed using chi-square tests or t tests, as appropriate for pairwise comparisons.

Results: A Snapshot of a Physician’s Workday

Our final sample comprised 61 physicians from 16 states and 28 practices: 29 primary care physicians (internal or family medicine), 14 non-interventional cardiologists, and 18 orthopedists (Table 2). The average physician age was 46.6 years, with 61.0% being men. A majority (67.2%) worked in hospital-owned practices, while 32.8% were in independent practices. All participants reported using EHRs. Physicians received an average of 9.2 beeps per workday and responded to an impressive 94.1% (531 out of 564) of these prompts.

Table 2: Characteristics of Participating Physicians and Their Practices

| Characteristic | Total (n = 61) | Primary care (n = 29) | Cardiology (n = 14) | Orthopedics (n = 18) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sex (% male) | 61% | 48%* | 53% | 78% |

| Age in years (x̅ ± sd) | 46.6 ± 11.9 | 48.6 ± 12.1 | 45.5 ± 12.0 | 44.1 ± 11.5 |

| Practice size | ||||

| 1–15 physicians | 26.2% | 31.0% | 14.3% | 27.8% |

| 16–100 physicians | 32.8% | 31.0% | 35.7% | 33.3% |

| > 100 physicians | 41.0% | 38.0% | 50.0% | 38.9% |

| Practice ownership? | ||||

| Hospital/hospital system | 67.2% | 75.8% | 71.4% | 50.0% |

| Independent physician | 32.8% | 24.2% | 28.6% | 50.0% |

| EHR time use in years (x̅, range) | 5.6, 1–15 | 6.9, 1–15* | 5.7, 1–12 | 3.3, 1–8 |

| Use scribe for EHR? | ||||

| Not at all | 85.2% | 93.2%* | 100%* | 61.1% |

| Occasionally | 9.8% | 3.4% | 0% | 27.8% |

| Often | 0% | 0% | 0% | 0% |

| Almost always | 5.0% | 3.4% | 0% | 11.1% |

Online survey responses from 61 physicians at study enrollment. EHR = electronic health record. p < 0.05 for statistically significant pairwise comparisons.*

During their office days, physicians spent approximately 10% of their time on personal activities (e.g., meals, personal calls). This “personal time” – representing 52 out of 531 total beeps – was excluded from further analysis to focus solely on work-related activities. As illustrated in Figure 1, after removing personal time, physicians allocated 66.5% of their time to Patient Care, 20.7% solely to EHR Input (separate from patient care), 7.7% to Administrative Work, and 5% to other activities (including Teaching/Supervising and Other miscellaneous tasks).

Figure 1: Physician Work Time Allocation by Specialty

Physician work time distribution by medical specialty, excluding personal time (10.0%). “Patient Care” encompasses direct patient interaction, care planning, and patient-related communication. “EHR Input” is time spent on electronic health records without concurrent patient care. “Administrative Work” includes tasks like meetings, insurance communication, and prior authorizations. “Other” includes teaching and miscellaneous activities. No statistically significant differences were found between specialties (chi-squared tests).

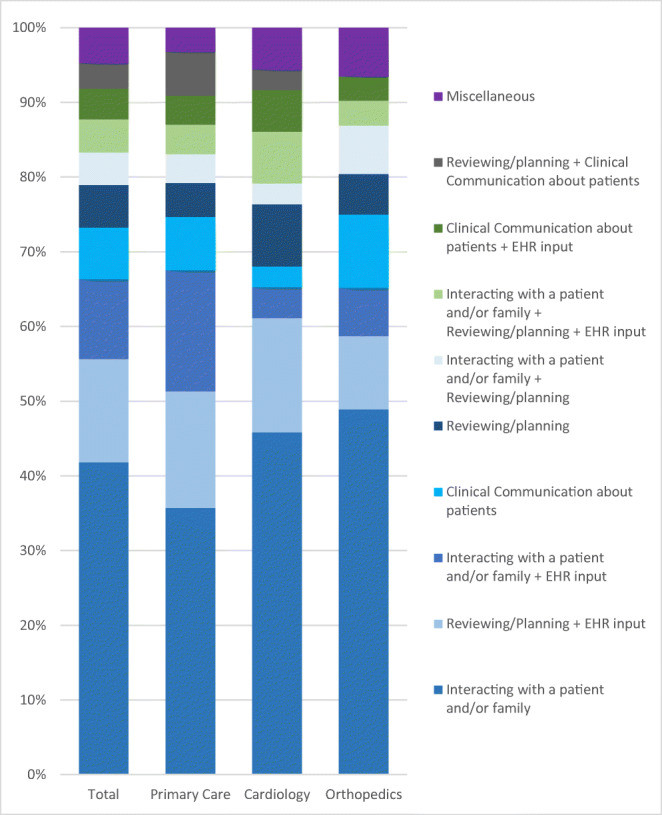

Of the 66.5% of time dedicated to Patient Care, 41.8% was spent exclusively in direct interaction with patients (Figure 2). An additional 24.5% involved patient interaction combined with EHR input, or reviewing/planning patient care alongside EHR use.

Figure 2: Breakdown of Activities Within Patient Care Time

Activities reported for the 66.5% of beeps categorized as Patient Care

Activities reported for the 66.5% of beeps categorized as Patient Care

Analysis of the 66.5% of physician time categorized as Patient Care. Shows the distribution of activities within this category, excluding personal time. “Clinical Communication” includes patient and healthcare team communication. Only the nine most frequent activity combinations are detailed; remaining combinations are grouped as “Miscellaneous.” No statistical tests were performed due to small category sizes.

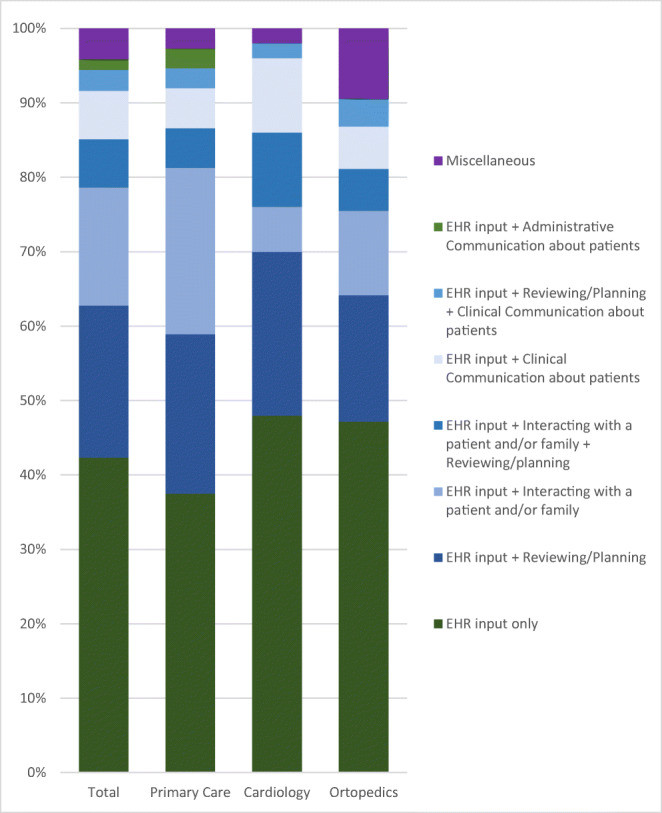

Physicians devoted 44.9% of their total work time (excluding personal time) to EHR-related activities (Figure 3). This included 20.7% solely on EHR Input, 23.6% on multitasking involving both EHR input and patient care (e.g., EHR input during patient encounters), and 0.6% on EHR input combined with teaching. While 42.3% of EHR time was spent on EHR input as a standalone activity, a larger 57.7% was spent in combination with other tasks, with patient care being the primary concurrent activity (52.6% of total EHR time).

Figure 3: Activities Associated with Electronic Health Record (EHR) Use

Activities reported for the 45.0% of beeps for which EHR use was indicated

Activities reported for the 45.0% of beeps for which EHR use was indicated

Analysis of the 45.0% of physician time involving EHR use. Shows activities performed when EHR input was indicated, excluding personal time. “Clinical Communication” is patient and healthcare team communication. “Administrative Communication” is communication with insurance, pharmacies, etc. The seven most frequent activity combinations are detailed; remaining are “Miscellaneous.” No statistical tests due to small category sizes.

No statistically significant differences in time allocation were observed across the three specialties (Figure 1). However, practice ownership significantly impacted time use (Figure 4). Physicians in physician-owned practices spent a greater proportion of their time on Patient Care (78.2%), compared to those in hospital-owned practices (61.6%, p < 0.05). Conversely, physicians in hospital-owned practices spent more time on EHR Input (23.2% vs. 14.8%, p < 0.05) and Administrative Work (11.7% vs. 4.9%, p < 0.05).

Figure 4: Physician Work Time Allocation by Practice Ownership

Physician work time by practice ownership model, excluding personal time. Categories are defined as in Figure 1. Statistically significant differences (chi-squared tests) were found between physician-owned and hospital-owned practices in time allocated to Patient Care, EHR Input, and Administrative Work (p < 0.05).

Discussion: Interpreting the Time Landscape for Physicians

Our findings reveal that physicians across various specialties dedicate the majority of their work time to patient care-related activities (66.5%), as opposed to EHR Input alone or Administrative Work (which together account for 28.4%).

Multitasking emerged as a common practice. Notably, of the 45.0% of total work time spent on EHRs, over half (57.7%) involved multitasking, often during patient encounters in the office.

These results offer a slightly different perspective compared to a time-and-motion study by Sinsky et al.[9] Their research, involving a similar physician group, reported only 27.0% of time in “direct clinical face time” and a substantial 49.2% on “EHR and desk work.” These discrepancies may stem from methodological differences. Our study captured more multitasking, offered a broader range of activity options (47 combinations), and categorized activities differently. Specifically, we classified certain EHR-related activities, such as “EHR input plus reviewing/planning,” as patient care, recognizing the integral role of care coordination in ambulatory practice.[10] Furthermore, Sinsky et al. relied on observers to categorize physician activities, while our study directly captured physician self-reporting, potentially eliminating observer bias and allowing measurement of activities in settings “closed to observation.”

To facilitate a more direct comparison with Sinsky et al., we re-analyzed our data, summing only activities involving direct patient contact or staff interactions related to immediate patient care. This yielded 50.0% of physician time (data not shown), still higher than Sinsky et al.’s 33.1%, but lower than our 66.5% when broadly defining Patient Care to include reviewing/planning.

Another study using EHR access logs by Tai-Seale et al. reported 49% of physician time on “face-to-face visits” and 51% on “desktop medicine.”[11] However, this log-based approach couldn’t capture time spent outside the EHR system or fully discern activities performed while logged in, nor did it measure multitasking.

Physician dissatisfaction with EHRs likely arises not only from the sheer time spent but also from factors like alert fatigue, excessive clicks,[12, 13] and reduced eye contact with patients.[14] Strategies to alleviate EHR burden, such as scribes, are being explored, but their cost-effectiveness remains under investigation.[15-17] In our sample, orthopedists used scribes more frequently than primary care physicians and cardiologists. While overall specialty-based time differences were not statistically significant, primary care physicians appeared to spend more time on combined EHR Input and Patient Care activities (48%) compared to orthopedists (35%), possibly reflecting the higher documentation demands for primary care, including performance reporting for payers.

The observed difference in time allocation by practice ownership—hospital-owned vs. independent—is noteworthy, particularly given the increasing hospital acquisition of physician practices.[18, 19] Physicians in hospital-owned practices spent significantly less time on patient care (61.6% vs. 78.2%) and more on EHR input (23.2% vs. 14.8%) and administrative tasks. The underlying reasons require further investigation, but could involve increased bureaucratic EHR expectations in hospital systems.

This study pioneers the use of EMA for physician time measurement. EMA offers several advantages over traditional time-and-motion studies. It can be scaled up more cost-effectively, minimizes observer bias, and captures activities in traditionally unobservable settings. Compared to EHR log analyses, EMA measures activities outside of EHR use and effectively captures multitasking, a common physician behavior.

Despite these strengths, our study has limitations. The sample size was relatively small, response rate was modest, and the convenience sampling method limits national representativeness. However, the study encompassed a wider range of practices than previous research.[9, 11, 20, 21] Furthermore, we couldn’t measure at-home EHR time, which is likely substantial.[5, 11, 22] Future research could combine EMA for office-based time with EHR log data for after-hours work.[11]

Recruitment challenges were encountered, primarily due to physician concerns about being beeped during patient interactions. However, participating physicians showed high compliance (94.1% response rate) and did not report the beeping as overly intrusive. Another challenge was the prevalent use of iPhones among physicians, while our app was Android-based. Providing loaner phones likely deterred some participation. Developing an iPhone-compatible EMA app could significantly enhance future participation.

Implementing EMA studies within practices, even large ones, could be cost-effective, especially with strong leadership support. Practices seeking to understand and optimize physician time use could encourage participation in such assessments, fostering discussions about time allocation and potential improvements. Large-scale EMA studies across numerous practices would be comparatively inexpensive, eliminating the need for costly observers. The high response rate in our study suggests that participation is not overly burdensome, and an iPhone app version could further streamline participation and reduce research overhead.

Conclusions: Reclaiming Time for Patient Care

Our findings offer a somewhat more optimistic view of physician time allocation toward patient care compared to earlier studies. However, the significant 45.0% of physician time spent on EHRs, either alone or in combination with other activities, remains a crucial concern, underscoring the need for continued efforts to reduce this EHR burden. While optimal physician time allocation remains an area needing further research, EHRs are widely recognized as a source of physician frustration and burnout.[2-4, 15, 24] Therefore, minimizing EHR-related time and enhancing user experience should be a priority.[25]

The fact that highly trained and expensive “time doctors” – physicians – spend only two-thirds of their time directly on patient care suggests a potential need for a fundamental rethinking of physician time utilization. This may necessitate changes in EHR systems, reimbursement models, and care delivery processes, with payment reforms incentivizing process improvements.[26] Ultimately, optimizing physician time is crucial for enhancing both patient care and physician well-being in the evolving healthcare landscape.

Electronic Supplementary Material

ESM 1 (1.1MB, docx) (DOCX 1098 kb)

Acknowledgments

The authors express their gratitude to Tania Gutsche, Bas Weerman, and Swaroop Samek for their contributions to the app development.

Funding Information

This research was supported by a grant from The Physicians Foundation.

Compliance with Ethical Standards

Conflict of Interest

Dr. Casalino reports personal fees from the American Medical Association Advisory Committee on Physician Professional Satisfaction and Practice Sustainability, outside of this submitted work. All other authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Footnotes

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature maintains neutrality regarding jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

(References are in the original article)

Associated Data

Supplementary Materials

ESM 1 (1.1MB, docx) (DOCX 1098 kb)