During times of devastating epidemics, particularly the plague outbreaks that ravaged Europe in the Middle Ages, a figure emerged as both a symbol of fear and a beacon of hope: The Plague Doctor. These physicians were specifically contracted by city governments to care for the infected, becoming a unique part of the era’s response to widespread disease. Their roles extended beyond medical treatment, encompassing a range of duties that reflected the desperate circumstances of the time.

Plague doctors were engaged by communities to attend to plague victims when general practitioners were hesitant to risk exposure. In periods of widespread panic and mortality, many established physicians fled, leaving a void filled by those willing to confront the disease directly. While some plague doctors were indeed trained medical professionals, including recent graduates or those struggling to find other work, a significant number had little to no formal medical training. Despite varying levels of expertise, their contracts typically obligated them to treat all plague sufferers, regardless of their ability to pay, and to venture into the most afflicted neighborhoods. Beyond attempting to heal the sick, their responsibilities included meticulously recording the grim statistics of infections and deaths, documenting wills for the dying, performing autopsies to understand the disease, and diligently keeping journals of their observations, all in the hope of contributing to the development of effective treatments or preventative measures.

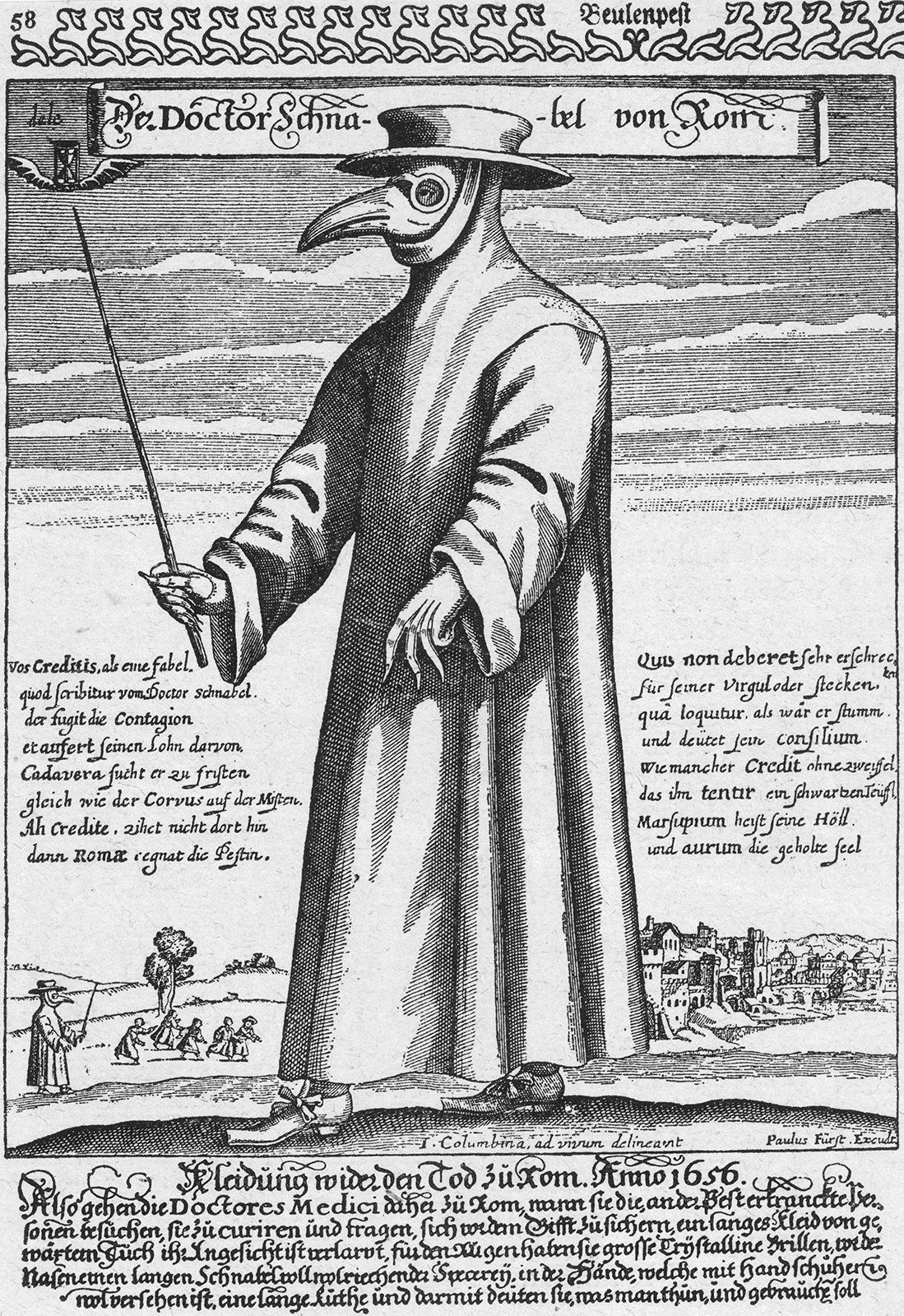

A plague doctor in protective clothing, circa 1656; engraving by Paul Fürst after J. Colombina.

A plague doctor in protective clothing, circa 1656; engraving by Paul Fürst after J. Colombina.

In an age where the understanding of disease was rudimentary, and the germ theory was centuries away, plague doctors operated under prevailing theories such as miasma theory – the belief that diseases were spread by foul-smelling air. Consequently, the treatments they administered were often rooted in these misconceptions and proved largely ineffective by modern standards. Common practices included bloodletting and the administration of emetics or diuretics, aimed at rebalancing the body’s humors – the four bodily fluids believed to govern health and temperament. These treatments, while aligned with the medical science of the time, did little to combat the plague itself.

However, the plague doctor’s most enduring legacy is undoubtedly their distinctive and unsettling attire. The iconic costume, often attributed to Charles de Lorme, a 17th-century French court physician, was designed as a form of protection against the perceived dangers of miasma. This garb consisted of a long, waxed coat, leggings extending into boots, gloves, and a wide-brimmed hat, all typically crafted from leather. The most striking feature was the beaked mask, equipped with glass or crystal eyepieces to shield the eyes. To further minimize physical contact, plague doctors carried a wand or staff, used to examine and direct patients without direct touch and to maintain what was considered a safe distance. The beak itself was not merely for show; it was filled with aromatic items such as lavender, mint, myrrh, camphor, or sponges soaked in vinegar, intended to filter out the noxious “bad air.”

While the miasma theory was incorrect, ironically, the plague doctor’s costume likely offered a degree of protection. The full-body covering could have shielded them from infected bodily fluids and respiratory droplets, and even from flea bites, the true vector of bubonic plague. Despite the grim context, the figure of the plague doctor, with their macabre appearance, became fodder for jokes and satirical cartoons. Their image transitioned into popular culture, becoming a recognizable character in Venetian Carnival celebrations and a stock character in Italian commedia dell’arte. Intriguingly, the plague doctor costume has seen a modern resurgence in popularity, particularly during the COVID-19 pandemic, as costume enthusiasts and even some protesters have adopted the garb, perhaps reflecting a continued fascination with this eerie figure from medical history and a poignant reminder of humanity’s enduring battles against epidemics.