During the terrifying reign of the Black Death in medieval Europe, a distinct figure emerged from the shadows of disease and despair: the plague doctor. These physicians, specifically contracted by cities and towns, were tasked with the grim responsibility of tending to the afflicted during devastating plague epidemics. While their methods were often ineffective by modern standards, and sometimes rooted in misguided theories, the image of the plague doctor, particularly their distinctive and eerie attire, has become an enduring and instantly recognizable symbol of the era.

Plague doctors were not general practitioners; instead, they were engaged during outbreaks to focus solely on plague victims. These contracts, meticulously drawn up by city officials, outlined their duties, geographical boundaries of service, compensation, and crucially, the mandate to care for all, regardless of social standing or ability to pay. This last point was particularly significant, ensuring that even the poorest, often residing in the most disease-ridden neighborhoods, received some form of medical attention, however rudimentary.

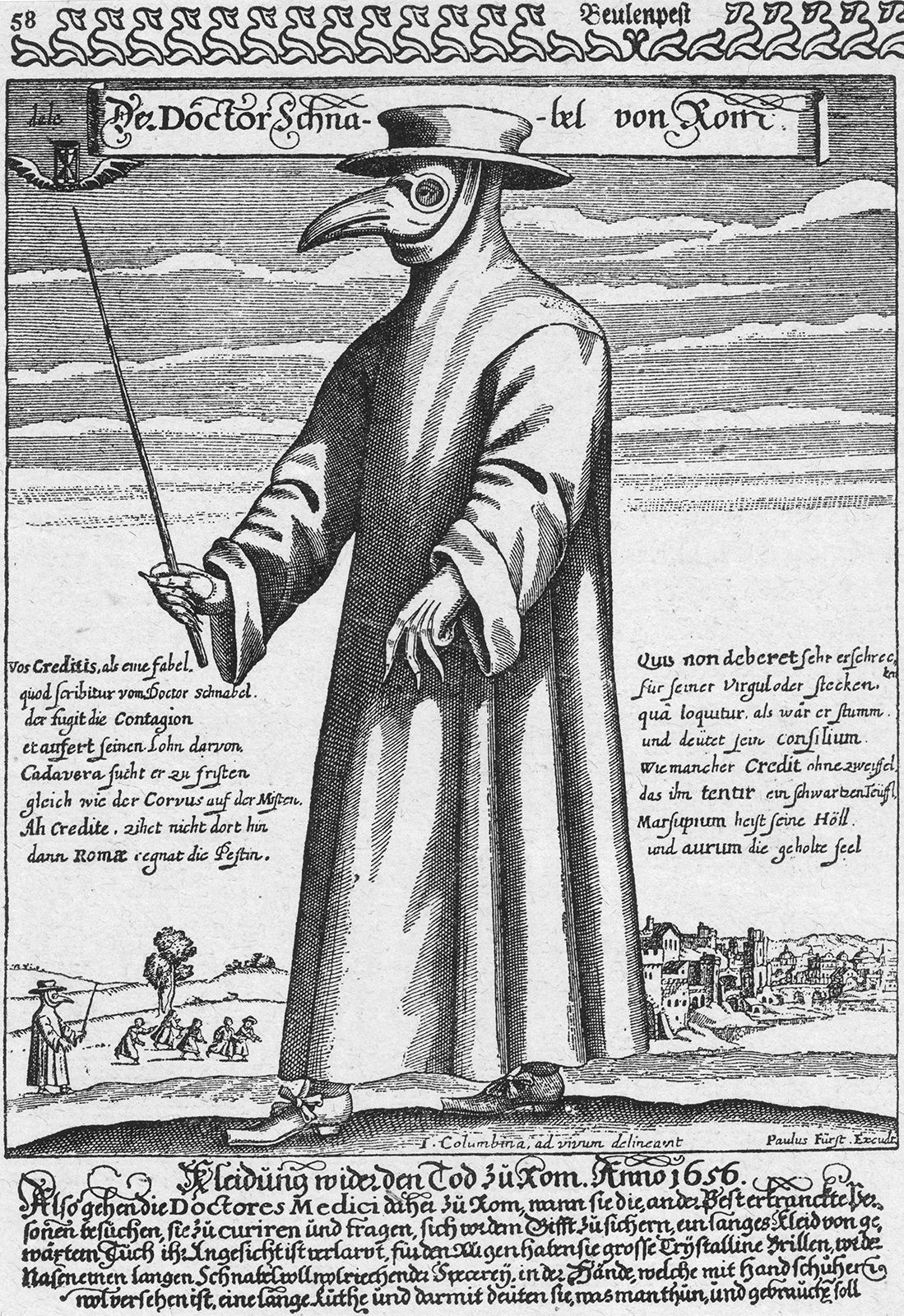

Engraving of a plague doctor in protective clothing, circa 1656, highlighting the iconic mask and long coat

Engraving of a plague doctor in protective clothing, circa 1656, highlighting the iconic mask and long coat

In times of widespread pestilence, the risk to regular physicians was immense. Exposure to the general populace significantly increased their chances of contracting the deadly disease. Therefore, the establishment of specialized plague doctors was seen as a pragmatic measure to protect the broader medical community and ensure some level of dedicated care for plague sufferers. However, the position of plague doctor was not always filled by the most experienced or qualified individuals. Many established doctors fled urban centers to avoid the plague, leaving a void in medical expertise. As a result, those who stepped forward to become plague doctors were a mixed group. Some were newly trained physicians or doctors struggling to establish their practices. Others, alarmingly, had no formal medical training whatsoever but were simply willing to face the danger when others were not. Despite the variation in their backgrounds and skills, plague doctors fulfilled crucial roles that extended beyond direct medical treatment. They were often tasked with meticulously recording the number of plague cases and fatalities, acting as witnesses for wills in plague-stricken households, conducting autopsies to understand the disease’s progression, and diligently documenting their observations in journals and casebooks. These records, though based on limited understanding, were intended to contribute to the development of future treatments and preventative strategies.

The treatments administered by plague doctors were, unfortunately, largely ineffective and sometimes even harmful. Operating under the prevailing medical theories of the time, which often centered on the concept of humorism and miasma theory, their approaches were misdirected. Common treatments included bloodletting and the draining of fluids from buboes – the characteristic swellings associated with bubonic plague. They also prescribed medicines designed to induce vomiting or urination, all in an attempt to rebalance the body’s supposed humors. These methods, while reflecting the medical understanding of the era, did little to combat the bacterial infection at the heart of the Black Death.

Yet, it is the distinctive and somewhat unsettling costume of the plague doctor that truly captures the imagination and remains their most enduring legacy. This iconic garb, typically attributed to Charles de Lorme, a 17th-century French court physician, consisted of several key components designed, in theory, to protect the wearer from disease. A long, waxed coat or gown, worn over leggings connected to boots, provided a full-body covering thought to repel the ‘bad air’ or miasma believed to transmit plague. Gloves, a hat, and most notably, a peculiar beaked mask completed the ensemble. The mask’s beak was not merely decorative; it was a crucial element, intended to be filled with strong-smelling herbs and flowers like lavender and mint, or substances like myrrh, vinegar-soaked sponges, or camphor. The rationale was that these potent aromas would counteract the miasma and purify the air breathed by the doctor. The mask also featured glass or crystal eyepieces to protect the eyes. Plague doctors often carried a wand or staff, used to examine and direct patients without physical contact and to maintain what was considered a safe distance from infection.

While the miasma theory underpinning the costume’s design was scientifically inaccurate, ironically, the outfit likely offered a degree of practical protection. The full-body covering could have shielded the wearer from infectious bodily fluids and respiratory droplets, and potentially even from flea bites, the true vectors of the plague. Beyond its functional (albeit unintentionally so) aspects, the plague doctor’s costume quickly became a potent symbol. It became a subject of macabre humor and satirical cartoons, and the figure of the plague doctor itself became easily recognizable as an ominous harbinger of disease and death. This striking attire found an unexpected second life at the Venetian Carnival, becoming a popular and somewhat unsettling costume choice. The plague doctor also became a stock character in the Italian commedia dell’arte, further cementing its place in popular culture. Remarkably, the costume has experienced a modern resurgence in popularity, particularly among costume enthusiasts and, perhaps unsurprisingly, during the COVID-19 pandemic, demonstrating the enduring and somewhat unsettling fascination with this figure from history.