During times of deadly outbreaks, particularly throughout the Middle Ages in Europe, governments sought individuals to care for the afflicted. These weren’t just any physicians; they were plague doctors. Engaged by cities or towns facing epidemics, their primary role was to specifically manage and treat plague patients. These contracts were formal agreements, outlining responsibilities, geographical limits, compensation, and often mandated the care of all, regardless of their ability to pay, especially in the most severely affected neighborhoods.

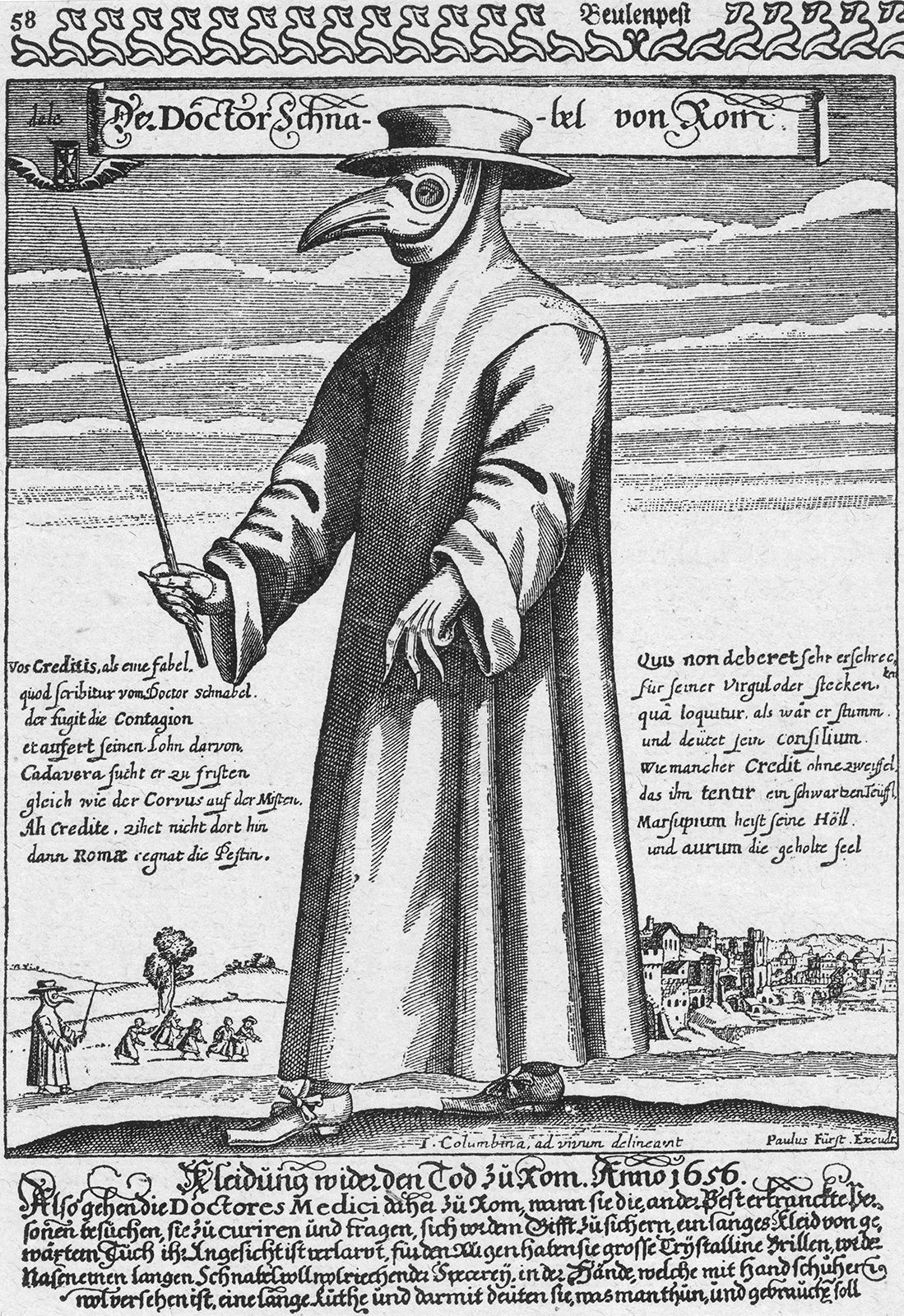

Plague Doctor in Protective Gear: 17th Century Engraving of Iconic Costume

Plague Doctor in Protective Gear: 17th Century Engraving of Iconic Costume

The rationale behind employing specialized plague doctors was rooted in risk mitigation. General physicians faced heightened exposure to the disease in their daily practice. Designating specific doctors for plague cases was considered a safer approach. Compounding the issue, many established and experienced doctors fled outbreaks, leaving a void filled by less experienced individuals. While some plague doctors were indeed medical trainees or those struggling to find conventional work, a number lacked formal medical training altogether. They were simply individuals willing to confront the plague directly when others would not. Their duties extended beyond medical treatment, encompassing vital public health functions such as recording infection and death tolls, witnessing legal wills, conducting autopsies to understand the disease, and documenting observations in journals to aid future treatment development and preventative strategies.

The treatments administered by plague doctors, in an era with limited understanding of disease, were diverse but largely ineffective. These methods often included bloodletting and draining fluids from buboes, the characteristic swellings of plague victims. They also prescribed medicines to induce vomiting or urination. These interventions stemmed from the prevailing medical theory of humourism, aiming to restore balance within the body’s supposed fluids.

However, plague doctors are most recognized today not for their treatments, but for their distinctive and iconic attire. This costume featured a long, waxed coat over leggings connected to boots, gloves, a hat, and most notably, a beaked mask. Leather was the primary material for most components. The mask incorporated glass or crystal eyepieces for eye protection. A wand or staff was also part of their equipment, used to examine patients or maintain distance without physical contact, believed to be a safe practice to avoid infection. Attribution for this costume design typically goes to Charles de Lorme, a 17th-century French court physician. Earlier plague outbreaks did not have a standardized outfit. This beaked costume became a source of dark humor and satire, with plague doctors themselves becoming grim symbols of disease and mortality. The attire gained popularity at the Venetian Carnival and became a recognizable stock character in Italian commedia dell’arte. Interestingly, the plague doctor costume has seen a modern resurgence, especially during the recent COVID-19 pandemic, embraced by costume enthusiasts.

The beak of the plague doctor mask was not merely for show. It was intentionally filled with potent aromatic substances like lavender, mint, myrrh, sponges soaked in vinegar, or camphor. Some plague doctors used theriac, a widely accepted cure-all since the 1st century CE. The dominant medical belief of the time attributed disease spread to “miasma,” foul-smelling air that disrupted bodily humors. The beak’s contents were intended to filter and purify this air, offering protection. While the theory behind the plague doctor’s costume was based on flawed science, the practical effect of the outfit may have offered a degree of protection. The full-body covering could shield against infectious bodily fluids and respiratory droplets, and potentially even flea bites, which were later discovered to be vectors of the plague.

In conclusion, plague doctors, though often using ineffective treatments by modern standards, played a crucial role during devastating epidemics. Their iconic and recognizable costume, particularly the beaked mask, remains a powerful symbol of those dark historical periods and continues to capture the imagination in contemporary culture.