Stanley Kubrick’s Dr. Strangelove or: How I Learned to Stop Worrying and Love the Bomb is a cinematic masterpiece that deepens in relevance with each passing year and every subsequent viewing. Beyond its obvious Cold War satire, this movie, Dr. Strangelove, increasingly feels like a crucial commentary on environmentalism, subtly critiquing the very nature of unquestioning professionalism and the modern concept of work itself.

My introduction to Dr. Strangelove was almost accidental. During childhood summer weeks spent at my aunt and uncle’s riverside cabin in Alabama, I stumbled upon it late one night. Around ten years old and seeking late-night entertainment, I navigated the UHF dial of an old television. The grainy image suggested a classic war film, and with limited channel options, I settled in, expecting boyhood thrills and adventure.

Adventure it certainly was, but of a profoundly different kind. As the movie concluded and the static of the sign-off followed the national anthem, my young mind was reeling. “What was that?” I wondered. The satire was lost on my ten-year-old comprehension, and the film’s pervasive adult humor sailed completely over my head. Yet, I was undeniably captivated. The image of a general producing a machine gun from a golf bag, the stoicism of the B-52 crew, and the melancholic melody of “When Johnny Comes Marching Home” accompanying the bombers on their grim mission – these elements resonated deeply.

From a climate fiction (Cli-Fi) perspective, Dr. Strangelove is often analyzed as a stark warning about the perils of thermonuclear war. This interpretation, while central to the film, was particularly resonant in the 1960s, a period defined by nuclear anxiety. The film’s premise is set in motion by the deranged Air Force officer, Brigadier General Jack D. Ripper (powerfully portrayed by Sterling Hayden), who initiates an unauthorized nuclear attack on the Soviet Union. Unbeknownst to Ripper, and revealed later to the US President and the assembled figures in the “War Room,” the Soviets have secretly constructed a “doomsday device.” This failsafe mechanism is designed to automatically trigger global annihilation in the event of a nuclear strike against Russia. The ensuing narrative becomes a desperate race against time to recall the bomber squadron and avert global catastrophe.

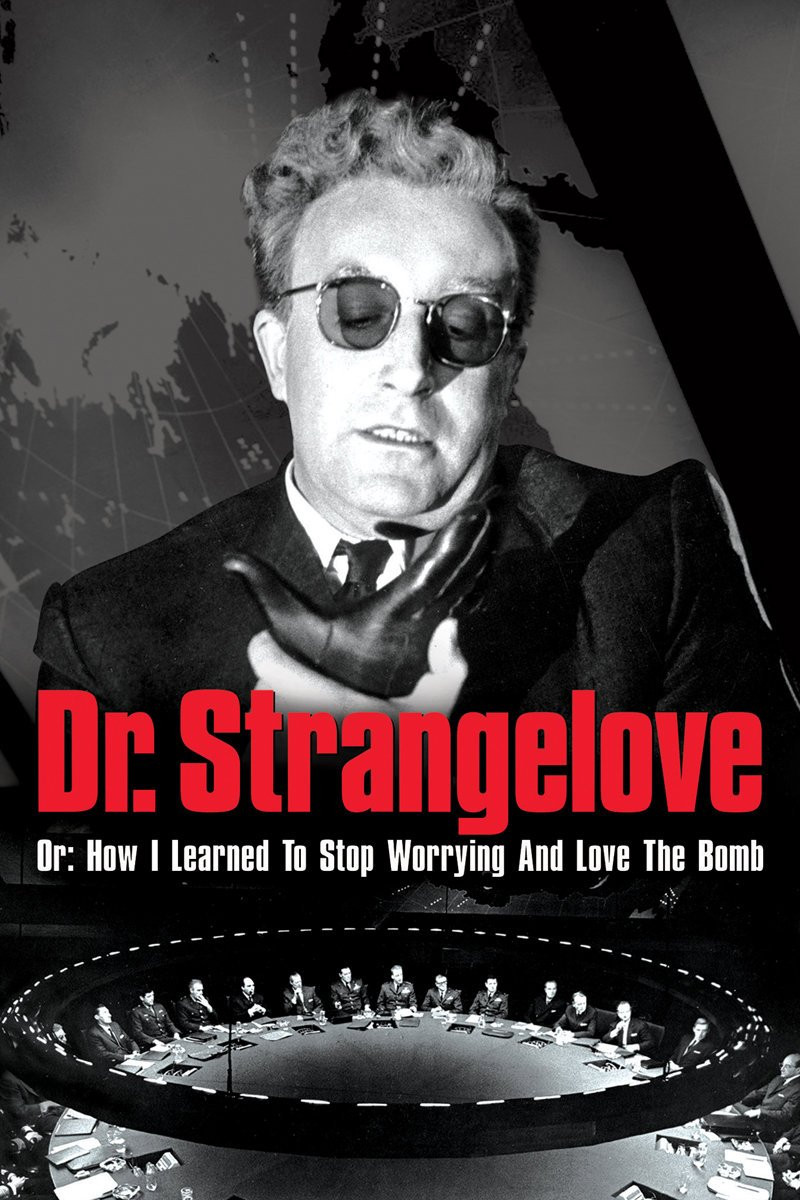

Dr. Strangelove movie poster featuring Peter Sellers, George C. Scott and Sterling Hayden

Dr. Strangelove movie poster featuring Peter Sellers, George C. Scott and Sterling Hayden

Released in 1964 and masterfully directed by Stanley Kubrick, Dr. Strangelove thrives on Cold War caricatures. We encounter the stereotypical drunken Soviet Premier (Dmitri Kissov), the well-meaning but ultimately ineffectual intellectual figure of the U.S. President Merkin Muffley, the steadfast British ally Group Captain Lionel Mandrake, the chillingly reformed Nazi scientist Dr. Strangelove himself, the shadowy and manipulative Soviet Ambassador Alexi de Sadesky, the rigidly bureaucratic military man (“You’re gonna have to answer to the Coca-Cola Company”), and a host of archetypal cowboy soldiers. The remarkable Peter Sellers embodies three of these pivotal roles: Muffley, Mandrake, and Strangelove, showcasing his unparalleled comedic range.

Originally, Sellers was intended to portray a fourth character, but an injury prevented this. The role instead went to Slim Pickens, who delivered an unforgettable performance as Major T. J. “King” Kong. While Kong embodies the surface-level cowboy persona, complete with a Texas drawl and Stetson hat, memorably riding a nuclear bomb like a rodeo bull in one of cinema’s most iconic scenes, his character runs deeper. Beneath the cowboy veneer, Kong is depicted as the ultimate professional: intelligent, rigorously trained, unwaveringly dedicated to his duty, and a natural leader who inspires unwavering loyalty and heroic action from his flight crew even in the face of unimaginable pressure.

Slim Pickens as Major Kong reading attack plans in Dr. Strangelove movie

Slim Pickens as Major Kong reading attack plans in Dr. Strangelove movie

Major Kong, despite his exemplary training and professionalism, lacked a critical element: the capacity for broader perspective and critical questioning. His fundamental flaw lies in his unquestioning acceptance of the mission, his implicit faith in the “go code” received from his commanding officer. Executing a “go code” with precision certainly demands intelligence and skill, but discerning the validity and ethical implications of that “go code” requires a far more nuanced and often undervalued attribute: wisdom. In essence, being well-trained is not synonymous with being well-reasoned or wise.

This crucial distinction – the challenge of cultivating wisdom, depth of understanding, and sound judgment – is eloquently explored by David Orr in his insightful book, Earth in Mind: On Education, Environment, and the Human Prospect. Orr argues that contemporary education, with its compartmentalization of knowledge into distinct disciplines, inadvertently encourages a fragmented worldview. This siloed approach hinders students’ ability to perceive the intricate interconnectedness within complex systems, such as the Earth’s delicate and multifaceted environment.

In his chapter “Dangers of Education,” Orr draws a provocative comparison between Albert Speer, Hitler’s chief architect and Minister of Armaments, and Aldo Leopold, widely considered the father of wildlife management. Initially, this juxtaposition might seem jarring. However, Orr’s comparison is profoundly insightful. Both Speer and Leopold were highly trained and accomplished individuals. Yet, Speer, despite his intellect and skills, succumbed to the rigid constraints of his specialized education, while Leopold transcended those limitations.

Orr quotes from Speer’s memoirs, written decades after World War II, where Speer reflects on his education, stating, “[Our education] impressed upon us that the distribution of power in society and the traditional authorities were part of the God-given order of things. … It never occurred to us to doubt the order of things.” Major Kong in Dr. Strangelove, much like Speer in his historical context, embodies this unquestioning acceptance of authority, never pausing to question the fundamental nature or implications of the orders he receives.

Conversely, Aldo Leopold retained and cultivated his capacity to perceive the intricate web of interdependencies that constitute our world – encompassing plants, animals, humanity, and the totality of human ideas and aspirations. This holistic perspective persisted despite his specialized training within a specific scientific discipline. Leopold’s ability to see both “the forest and the trees” led to his development of the revolutionary Land Ethic, a philosophical framework positing that true understanding of our environment necessitates a deep and abiding affinity for it.

Returning to Dr. Strangelove, Major Kong’s fateful decision to proceed with the bombing mission against the Soviet Union is made with minimal reflection. However, the consequences are swift and impactful. Shortly after breaching Soviet airspace, the B-52 bomber sustains damage from a missile strike. This critical damage prevents the crew from receiving the crucial recall order, thereby establishing the central dramatic tension that propels the film’s final act: Will Kong and his crew succeed in their mission, potentially triggering the doomsday device and global annihilation?

The true embodiment of the unchecked “cowboy” ethos in Dr. Strangelove is General “Buck” Turgidson, played with scene-stealing gusto by George C. Scott. When questioned about the Soviet Union’s potential to intercept the rogue B-52 bomber, Turgidson erupts with disturbing enthusiasm, exclaiming, “If the pilot’s good, see, I mean if he’s reeeally sharp, he can barrel that baby in so low … oh you oughta see it sometime. It’s a sight. A big plane like a ’52—varrrooom! Its jet exhaust … frying chickens in the barnyard!” In Turgidson’s twisted logic, a pilot’s professionalism and skill are measured by their unwavering ability to complete the mission, regardless of the catastrophic implications.

The horrified silence and appalled stares from the other War Room members underscore the chilling absurdity of Turgidson’s perspective. The realization slowly dawns upon him – and the audience – that the fate of humanity rests on Kong and his crew failing their mission, not succeeding.

What parallel realization is slowly dawning on us today? The global pause induced by the coronavirus pandemic – the worldwide lockdowns that precipitated a dramatic contraction in economic activity, resulting in reduced traffic, decreased emissions, cleaner air, and a resurgence of wildlife in unexpected places – starkly illuminated the fundamental nature of the global economy. It revealed it to be, in essence, a colossal machine relentlessly consuming our planet, Earth.

Those of us working within the architecture, engineering, and construction (AEC) industry are undeniably integral components of this machine. The sheer volume of raw materials and energy consumed in building construction, and the even greater energy demands of operating these buildings over their lifespans, position the AEC sector as a significant contributor to environmental impact. Our prevailing response to this crisis often amounts to applying a superficial “green veneer” to the existing system – marginally improved HVAC systems, low-VOC paints, rooftop solar panels. However, this approach, while seemingly progressive, often implicitly endorses what might be termed the “Triple Bottom Lie.” This fallacy suggests that perpetual growth – more people, increased individual consumption, and an economic system utterly reliant on these factors – can continue indefinitely without dire consequences. It is a comforting illusion, aligning neatly with the seductive allure of the invisible hand of the market. After all, innovation is touted as an inexhaustible resource, and the vast resources of asteroids are waiting to be exploited.

The architectural profession’s apparent unpreparedness for the climate crisis is, perhaps, not entirely surprising. The dominant paradigms of architectural thought – the diluted remnants of 20th-century Modernism – emerged and solidified during an era of unprecedented and ultimately unsustainable global population growth and resource consumption. Intellectually, we remain largely tethered to the worldviews of figures like Corbusier and Frank Lloyd Wright, with their unwavering faith in technological progress and seemingly limitless horizons. And who can truly fault this inclination? The allure of frontier nostalgia is undeniably more appealing than confronting the imperative of intelligent and sustainable retreat.

A defining challenge of the early 21st century is the widely lamented “death of expertise.” (The disjointed and ineffective federal response to the coronavirus pandemic in the U.S. serves as a stark example). However, an equally critical, and perhaps more insidious, challenge lies in the deployment of expertise toward detrimental ends.

While movements such as Architecture 2030 and Architects Declare are gaining crucial momentum, a significant portion of the architectural profession continues to design and construct buildings as if the environmental realities of the 21st century were nonexistent, as if it were still 1970. Conversely, others, overwhelmed by the scale and complexity of the climate crisis, succumb to a sense of fatalism, declaring “Game over, man!” and abandoning meaningful climate mitigation efforts. This resignation may stem from the perceived difficulty of truly addressing the climate crisis, or perhaps from the profound challenges it poses to deeply entrenched economic orthodoxies.

The enduring Cli-Fi lesson of Dr. Strangelove, the movie, resonates powerfully today: Like Major Kong, professionals across numerous fields, including architects, are often intelligent, highly trained, dedicated, and natural leaders – working with immense effort and commitment, frequently in service of fundamentally flawed and ultimately destructive systems.

Ladies and gentlemen, raise your hats and join in the chillingly ironic cheer: “Yee-haw!” The mission, in its most terrifying and literal sense, is nearing completion.

All motion picture dialog is from imdb.com.