The voicemail was clear, yet utterly baffling. A woman’s voice informed me to call back regarding my “Top Doctor” award, emphasizing the need to “ensure everything’s accurate” before sending the prestigious plaque. The irony wasn’t lost on me. I am no physician; a medical degree is not on my resume. My expertise lies in investigative journalism, specifically within the intricate realm of healthcare. Intrigued and amused, I promptly returned the call from this Long Island-based company, the purveyors of the Top Doctor Awards. On the other end was Anne, a cheerful salesperson who, mistakenly believing I was a doctor and deserving of their accolade, launched into her pitch. I listened intently, taking detailed notes, a journalist in my element.

She explained the selection process – peer nominations and patient reviews, painting a picture of me as a “leading physician.” Dismissing the call as farcical was tempting, but I recognized the underlying dynamic: the confluence of doctors’ egos and patients’ earnest quest for competent medical professionals. Many patients place undue faith in these awards, assuming rigorous vetting and high standards are in place to identify only the truly “best” doctors. This facade of credibility is further bolstered by hospitals and physicians themselves, proudly displaying these accolades in their offices and on their websites.

And somehow, inexplicably, Top Doctor Awards had selected me – arguably the least suitable recipient imaginable. For over a decade, I’ve dedicated my career to healthcare reporting, scrutinizing the very systems used to measure physician quality. Medicine is nuanced; definitively labeling one doctor “better” than another is an oversimplification. Evaluating physician performance, from diagnostic accuracy to surgical outcomes and patient satisfaction, is a complex undertaking. Yet, for-profit entities continuously churn out “Super,” “Top,” or “Best” doctor lists, promoting them through magazine advertisements, online directories, and, of course, those coveted shiny plaques and promotional videos, available for an additional fee.

Our conversation took an even more surreal turn when Anne mentioned my employer, ProPublica. At least she had that detail correct. I clarified my role: a journalist, not a physician. “Is that a problem?” I inquired. “Or can I still receive the ‘Top Doctor’ award?”

A pause followed, a clear deviation from her script. But Anne, ever the salesperson, quickly recovered. “Yes,” she affirmed, I was still eligible for the award. Her commission, I surmised, must be heavily reliant on volume.

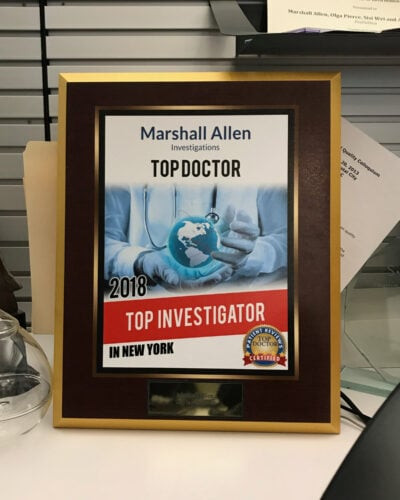

Then came the crucial details. The honor included a personalized plaque, with a choice of cherry wood with gold trim or a more contemporary black with chrome trim. I pondered which aesthetic better suited my unique brand of “medicine” – traditional or modern?

“There’s a nominal fee for the recognition,” Anne continued, reverting to her scripted cadence. “A reduced rate of just $289. We accept Visa, Mastercard, and American Express.”

Even as a peculiar reporting expense, $289 seemed steep for ProPublica’s budget. I hesitated.

“The plaque commemorates your achievements and, more importantly, communicates those achievements to your patients,” she pressed, moving in for the close. “It’s a significant achievement. I’d hate for you to miss out. I can offer it to you right now for $99.”

I accepted. And just like that, I became a “Top Doctor.” A far cry from years of medical school and crippling debt, I mused. And it certainly added a certain gravitas to my pronouncements in the newsroom, like advising colleagues to “Go home before we all get sick.”

The dubious standards of Top Doctor Awards were glaringly obvious. But it sparked my curiosity about the myriad other awards plastered online and throughout local lifestyle magazines. Castle Connolly Top Doctors, Super Doctors, Best Docs – the list went on. The deeper I delved, the more companies I discovered lavishing praise on doctors, then charging them to publicize it. What were their selection criteria? And who were these doctors willingly accepting these accolades? I wondered how they would react to the revelation that I, too, was now among their esteemed ranks.

Marshall Allen’s “Top Doctor” award. (Hannah Birch/ProPublica)

Marshall Allen’s “Top Doctor” award. (Hannah Birch/ProPublica)

My first step was to consult genuine healthcare quality experts. Unsurprisingly, their opinions were less than favorable. “This is a scam,” declared Dr. Michael Carome, director of the health research group at Public Citizen, a consumer advocacy organization. “Any competent, qualified doctor doesn’t need one of these awards, unless it’s to inflate their ego. These awards are meaningless, worthless.”

Carome went further, deeming it unethical for companies to issue these awards and for doctors to accept them.

Naturally, the companies behind these for-profit doctor rating systems vehemently defended their legitimacy, particularly when compared to their competitors.

John Connolly, co-founder of Castle Connolly Top Doctors, couldn’t resist a jab at my award. “What’s your specialty, Dr. Marshall?” he quipped. “I certainly hope you’re not performing surgery.”

Connolly claimed his company relied on peer nominations to identify “top doctors.” He stated their New York City-based research team verified each nominee’s license, board certification, education, and disciplinary history – information readily available to the public on regulatory websites. These checks, at least, would likely prevent someone like myself from slipping into the “top doctor” pool.

Connolly conceded it would be “very difficult” to manipulate the nomination process, but offered a verbal disclaimer: “We don’t claim they are the best,” he clarified regarding his company’s honorees. “We say they are ‘among the best’ and ones we have carefully screened.”

Doctors deemed “among the best” by Castle Connolly can enhance their online profiles for a fee. Plaques are also available for purchase. Further revenue is generated through partnerships with magazines for promotional issues in various cities and regions. “The ‘Top Doctor’ issue is typically the number one seller for newsstands and advertising,” Connolly revealed.

Super Doctors, based in Minnesota, employs a similar methodology – physician nominations and credential verification. Their disclaimer, however, is even more explicit, explicitly stating that being named a “Super Doctor” doesn’t guarantee superior medical skills: “No representation is made that the quality of the medical services provided by the physicians listed in this Web site will be greater than that of other licensed physicians.”

Becky Kittelson, research director for Super Doctors, explained, “It’s a listing people can use as a starting point. We never suggest it’s the only place to look.”

Like Castle Connolly, Super Doctors also generates income by offering upgraded website listings and commemorative plaques, as well as selling advertisements in publications featuring their doctors.

Those glossy magazine spreads showcasing “The Best” plastic surgeons, orthopedic specialists, and other medical professionals in airline in-flight magazines? Those are often advertising sections orchestrated by Madison Media Corp., based in New York City. They essentially piggyback on the efforts of companies like Castle Connolly and Super Doctors. Doctors recognized by those services can then purchase ads to be featured in airline publications, according to John Rissi, president and owner of Madison Media.

But how does Rissi ascertain that “The Best” doctors in his ads are genuinely the best? “I suppose in this world, finding the absolute best is difficult,” he admitted. “It’s all based on reputation and interpretation.”

Healthcare quality experts scoffed at this notion. Dr. John Santa, who previously spearheaded healthcare quality measurement initiatives for Consumer Reports magazine, pointed out the inherent flaws in nomination-based systems. These systems, he argued, are easily manipulated by doctors with intertwined financial interests – partners within the same practice or doctors who regularly refer patients to one another. “If you examine these methodologies, they are riddled with economic and relationship biases,” Santa asserted.

Santa condemned these vanity awards as an insult to patients who deserve reliable information when seeking medical care. Even the most rigorous of these awards, he contended, merely verify basic credentials. “Frankly, being in good standing with a state licensing board is a very low bar,” Santa stated. “Board certification is also a very low bar.”

Months after my own “Top Doctor” induction, I decided to probe further into Top Doctor Awards’ selection process, without disclosing my own dubious “honor.” I was directed to Donna Martin in client services. She reiterated that “Top Doctors” could be nominated by peers for their achievements. However, she also mentioned a “full interview process” encompassing questions about education, leadership, and awards (no one had inquired about my English degree from the University of Colorado, I noted).

My interest piqued when she mentioned a research team, but further details about their methods were, she stated, proprietary.

I called Martin back later, posing the question directly: How robust could their methods be if someone like me, a journalist – “I’m a doctor not a” – was deemed a “Top Doctor?” She promised to review my account and call me back. I’m still awaiting that call.

What about my fellow “Top Doctors,” the actual physicians sharing this award? Were they aware of the questionable nature of this recognition? I contacted Dr. Lewis Maharam, a sports medicine specialist in New York City who brands himself as the “Running Doc.” He expressed no surprise at being recognized by Top Doctor Awards, citing a wall adorned with similar accolades. “I’m in that echelon or class,” he stated. “If you’re finding people who don’t deserve [the awards], then perhaps you’re onto something.”

I then revealed my own “Top Doctor” status.

“That’s pretty strong evidence that it’s not legitimate,” he conceded, his tone shifting. “It’s possible my assistant simply sent in a check.”

Maharam suggested that busy doctors are easily targeted by such schemes. Being included in these lists, even if questionable, can attract patients, he admitted. However, he vowed to inquire about selection methods for future offers and indicated he might reconsider paying the renewal fee for his 2019 “Top Doctor” award, now knowing my story. I didn’t take it personally.

I reached out to approximately a dozen other “Top Doctors” – orthopedic and gynecologic surgeons, an allergist, an infectious disease specialist, even an orthodontist, scattered across the country. There were so many, I could have continued for days. Mostly, I left voicemails. I did speak to a few assistants, who seemed alarmed to learn of my “Top Doctor” affiliation. Maharam was the only one who returned my call directly.

A few weeks later, my faux cherry wood and gold “Top Doctor” plaque arrived at the ProPublica newsroom. I couldn’t help but smile with a touch of ironic pride. The salesperson had asked for my specialty. The whole charade was so absurd, I could have claimed neurosurgery. But journalistic integrity prevailed, and I truthfully stated “investigations.”