Celebrating five decades of Doctor Who, the iconic science fiction series, compels us to revisit standout episodes. Among these, Silence in the Library, penned by Steven Moffat, remains a fascinating, if slightly familiar, entry. Originally broadcast in 2008, this story, and its continuation in Forest of the Dead, arrived with considerable anticipation, especially given Moffat’s prior successes within the Doctor Who universe.

“There’s the real world, and there’s the world of nightmares. That’s right, isn’t it? You understand that?”

“Yes, I know, Doctor Moon.”

“What I want you to remember is this, and I know it’s hard. The real world is a lie, and your nightmares are real.”

– Cal and Doctor Moon, hinting at the unsettling core of Moffat’s narrative.

Silence in the Library holds a peculiar position in Steven Moffat’s Doctor Who repertoire. While not eclipsing the sheer brilliance of The Empty Child/The Doctor Dances, The Girl in the Fireplace, or Blink, it’s undeniably a strong story. Perhaps the weight of expectation, set by Moffat’s earlier, Hugo-awarded episodes, cast a slight shadow. To suggest it doesn’t quite reach the heights of Midnight, another standout from the same season, is not a harsh critique, but rather an acknowledgement of the incredibly high bar set by Season 4 of the revived series.

I find myself quite drawn to this two-part adventure, even while recognizing certain shortcomings. By this point in the revived series, audiences had become attuned to “Moffat-isms.” The narrative tricks, the genre tropes – while expertly employed – were becoming recognizable. Silence in the Library, while skillfully crafted and effectively executed, treads slightly familiar ground within Moffat’s established storytelling landscape.

Going by the book on this one in Doctor Who Silence in the Library.

Going by the book on this one in Doctor Who Silence in the Library.

Russell T. Davies’ fourth season as showrunner for Doctor Who feels celebratory. This season embraces the show’s rich history, nodding towards classic episodes like The Romans, The Sensorites, and Survival. It also acknowledges the significant evolution of Doctor Who since its 2005 revival. Notably, there are several overtures to Moffat’s earlier contributions to the series.

The Poison Sky saw the Doctor himself echoing Moffat’s memorable “Are you my mummy?” catchphrase from The Empty Child, while wearing a gas mask – a clear homage. The Fires of Pompeii concluded with a stinger that had Jack Harkness referencing “volcano day,” again borrowing Moffat’s dialogue. Considering Moffat’s impending succession of Davies as showrunner, these instances feel like a symbolic passing of the creative torch, a celebration of both eras.

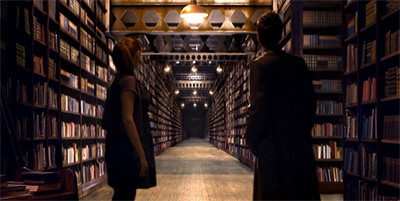

The dimly lit corridors of the Library in Doctor Who Silence in the Library episode.

The dimly lit corridors of the Library in Doctor Who Silence in the Library episode.

Silence in the Library and Forest of the Dead fit seamlessly into this celebratory atmosphere. They serve as a thematic bookend to the first season of the revived show. Davies entrusted Moffat with the second two-parter of his final season, mirroring the assignment he gave Moffat in the revival’s inaugural year. While Silence in the Library showcases many of Moffat’s signature storytelling devices, it also harkens back to his initial Doctor Who scripts.

The line, “Hey, who turned out the lights?” is a deliberate attempt to create a memorable monster catchphrase, akin to “Are you my mummy?” from The Empty Child, even if it doesn’t quite achieve the same iconic status. River Song, introduced here, can be interpreted as a counterpart to Captain Jack Harkness. Moffat only wrote Jack’s debut appearance prior to this, but crafted him so effectively. The narrative touches upon uncomfortable family secrets and even concludes with an “everybody lives” sentiment, reminiscent of The Doctor Dances from three years prior.

Staying alive is key in Doctor Who Silence in the Library.

Staying alive is key in Doctor Who Silence in the Library.

Further familiar Moffat elements permeate the story. The episode exemplifies Moffat’s talent for making the ordinary terrifying, as seen in Blink with statues, and here with shadows. There’s the recurring motif of technology with good intentions going awry, a plot device present in The Doctor Dances and The Girl in the Fireplace. The non-linear romance from The Girl in the Fireplace feels like a precursor to River Song’s relationship with the Doctor, a connection existing outside of chronological order.

These recurring story elements are not inherently negative. Many Doctor Who writers possess their own favored narrative techniques. Davies often employs vaguely foreshadowed deus ex machina resolutions. Terrence Dicks’ Doctor Who novels are known for their distinctive phrases. Robert Holmes frequently utilized double acts and obstructive bureaucratic figures. A keen observer can readily identify the authorial voice of various Doctor Who writers through their recurring narrative patterns.

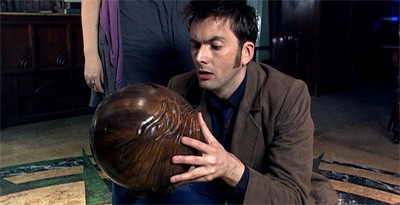

No bones about it, the Vashta Nerada are scary in Doctor Who Silence in the Library.

No bones about it, the Vashta Nerada are scary in Doctor Who Silence in the Library.

Moffat is no exception. He has his own set of preferred hooks and narrative devices. Under his leadership as showrunner, Doctor Who embraced “timey-wimey” narratives, with each season relying on time-related narrative complexities. However, these temporal themes are distinct across seasons, each possessing a unique flavor. The overarching plot of Season 5, centered on a universe-resetting event, differs from the intricate, non-linear biography of River Song in Season 6, and both are distinct from the mystery surrounding Clara Oswald in Season 7.

Yet, novelty holds significant value. The impact of Moffat’s The Empty Child stemmed partly from its unexpected brilliance. While Moffat had a substantial television background, much of his pre-Doctor Who work was in youth dramas or sitcoms. Although he later created successful genre shows like Sherlock and Jekyll, before Rose aired in 2005, he hadn’t ventured into similar territory.

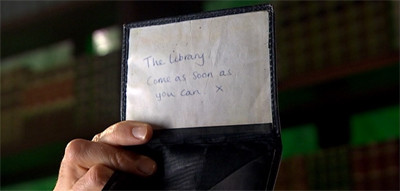

The ominous "X" marks the spot in Doctor Who Silence in the Library.

The ominous "X" marks the spot in Doctor Who Silence in the Library.

One could argue Russell T. Davies was also relatively unproven in the Doctor Who context, but his prior work felt more aligned with the show’s tone. Davies had produced bold, provocative television like The Second Coming, whereas Moffat was known for Press Gang and Coupling. While Davies had explored darker themes in his Doctor Who novel Damaged Goods, Moffat’s sole contribution was the comedic spoof The Curse of Fatal Death.

Therefore, Moffat’s The Empty Child and The Doctor Dances scripts were revelatory. While his skill with romantic comedy, evident in the Doctor-Rose-Jack dynamic, was anticipated, the profound scariness of those episodes was genuinely surprising. Moffat proved himself exceptionally adept at crafting effective horror.

A packed lunch for a trip to the library in Doctor Who Silence in the Library.

A packed lunch for a trip to the library in Doctor Who Silence in the Library.

Then came The Girl in the Fireplace. Before its broadcast, The Empty Child and The Doctor Dances could have been seen as outliers. However, Moffat’s second script solidified his status as a major talent. Retrospective viewing reveals interconnected threads. The “timey-wimey” concepts hinted at in The Empty Child/The Doctor Dances (Jack’s time travel scams) evolved through The Girl in the Fireplace and Blink. Each time, these concepts became more intricate and layered.

However, there’s a limit to the temporal mechanics one can explore within a 45-minute episode. Moffat arguably reached that point with Blink, which employed time travel to force individuals to “live themselves to death” and featured recorded conversations spanning decades. Beyond this saturation point, the options are to either accept limitations or expand beyond a single episode’s scope.

Donna's confused state in Doctor Who Silence in the Library.

Donna's confused state in Doctor Who Silence in the Library.

From 2010 onwards, as showrunner, Moffat could extend his time-travel arcs across entire seasons. Yet, in Silence in the Library and Forest of the Dead, he was constrained by the single-story format. Consequently, aspects of the episode feel familiar. The Doctor-River Song dynamic, lacking the development it would receive in later seasons, feels like a re-exploration of the Doctor-Madame de Pompadour relationship, rather than the groundbreaking setup for Moffat’s showrunner era it would become.

Silence in the Library possesses a nostalgic quality for Moffat. Emails in The Writer’s Tale suggest Moffat was developing the script while considering Davies’ showrunner offer. It’s plausible that Silence in the Library is a nostalgic return to Moffat’s initial scripts for Davies, perhaps even further back. The episode directly engages with Doctor Who as a franchise, arguably more explicitly than when he incorporated Star Trek references into The Empty Child.

"Book him, boys" – a humorous moment in Doctor Who Silence in the Library.

"Book him, boys" – a humorous moment in Doctor Who Silence in the Library.

Like many Moffat scripts, Silence in the Library features malfunctioning technology. Here, however, this glitchy tech has a meta-fictional dimension. Throughout Silence in the Library and Forest of the Dead, we repeatedly cut to Cal, a young girl in an apartment with her father. Cal is watching the Doctor on television – watching Doctor Who. We witness her reactions – the excitement, fear, and laughter – as she watches the Doctor’s adventures, while interacting with a counselor who helps her process her emotions and nightmares.

A particularly memorable scene in Silence in the Library shows the Doctor communicating with Cal through her television screen – a surreal moment reminiscent of Attack of the Graske integrated into the main narrative. Moffat establishes that, for Cal, she is watching a television program featuring corridor chases and monster encounters. At the beginning of Forest of the Dead, Cal simply changes channels to watch a mundane soap opera, highlighting the contrast between the Doctor’s extraordinary world and ordinary life. This is a Doctor Who episode featuring a character watching Doctor Who.

Doctor Who now in stunning HD as seen in Silence in the Library.

Doctor Who now in stunning HD as seen in Silence in the Library.

This meta-narrative element aligns with the celebratory tone of Season 4. The season culminates in the return of virtually every companion since 2005, making a two-parter where a character watches Doctor Who feel less jarring, especially given Doctor Who‘s prominence in British television. Cal’s perspective never overshadows the main narrative, preventing the meta-fiction from becoming overly self-indulgent.

If Silence in the Library is a nostalgic reflection, the library setting is particularly apt. When Doctor Who was off the air, tie-in novels kept the franchise alive. Talented authors contributed to these books, maintaining Doctor Who‘s relevance. Many of these writers, including Russell T. Davies, Mark Gatiss, Paul Cornell, and Gareth Roberts, later wrote for the revived series. These novels, in many ways, “saved” Doctor Who, preserving it for its eventual return to television.

Shedding some light on the Vashta Nerada threat in Doctor Who Silence in the Library.

Shedding some light on the Vashta Nerada threat in Doctor Who Silence in the Library.

Silence in the Library also seems to reflect on Moffat’s pre-Doctor Who career. The Doctor observes that life without death would be mere comedy. “You need a good death,” he asserts. “Without death, there’d only be comedies. Dying gives us size.” Given that both Silence in the Library and The Doctor Dances conclude with “everybody lives” resolutions, Moffat might be suggesting that Doctor Who shares a close affinity with comedy, a genre he was intimately familiar with.

Other Moffat-esque touches abound. While Davies often portrays the Doctor as a “Lonely God,” Moffat leans towards a fairy-tale interpretation. Silence in the Library embraces this theme, previously explored in The Girl in the Fireplace. Murray Gold’s score evokes a music box quality, and the entire episode feels like a hazy, half-remembered dream from a child’s perspective. When Doctor Moon asks Cal about navigating the library, she replies, “By wishing.”

Eavesdropping in the library in Doctor Who Silence in the Library.

Eavesdropping in the library in Doctor Who Silence in the Library.

Moffat also subtly introduces the “Doctor’s name” mystery here. River Song knows his name, though it remains undisclosed to the audience. Furthermore, Moffat hints that “the Doctor” might be sufficient, emphasizing the definitive article. Discussing the library, the Doctor remarks, “The Library. So big it doesn’t need a name. Just a great big The.” This foreshadows River’s “we get that word from you” speech in A Good Man Goes to War, suggesting the title itself is significant.

Steven Moffat possesses a distinct approach to Doctor Who, already well-defined by Silence in the Library. Perhaps criticizing Moffat for having a limited set of truly great ideas that he revisits is unfair. The backlash against Moffat might stem from the fact that he had already established his Doctor Who style for four years before becoming showrunner.

Lights out in the Biographies section of the Library in Doctor Who Silence in the Library.

Lights out in the Biographies section of the Library in Doctor Who Silence in the Library.

Silence in the Library showcases a structured approach to Doctor Who, but one that feels less groundbreaking than Moffat’s initial forays. His key technique is to transform the mundane into the terrifying. In The Empty Child, it was a gas-masked child. In The Girl in the Fireplace, the ticking clock. In Blink, statues. Here, it’s a skipping audio track and shadows.

Shadows are inherently unsettling, even before Moffat’s “piranhas of the air” concept. “Every shadow?” River asks. “No,” the Doctor replies, “But any shadow.” Fear of the dark is primal, making it fertile ground for horror. “Almost every species in the universe has an irrational fear of the dark,” the Doctor explains, “But they’re wrong, because it’s not irrational.” This is a compelling hook, although visually, “shadows” are harder to render menacing on a BBC budget than a gas-masked child, clockwork robots, or Weeping Angels.

Hello sweetie – River Song's iconic line in Doctor Who Silence in the Library.

Hello sweetie – River Song's iconic line in Doctor Who Silence in the Library.

Familiarity can breed apathy, and this might partly explain why Silence in the Library isn’t as universally praised as some of Moffat’s other episodes. Having witnessed these narrative techniques before, their assembly in a two-parter from the incoming showrunner feels somewhat less impactful. While perhaps not entirely justified, this sentiment contributes to the slightly peculiar reception of Silence in the Library.

Furthermore, Forest of the Dead, the second part, has been critiqued for its gender dynamics. Beyond that, the two-parter as a whole suggests a slight mischaracterization of Donna Noble. In the opening scenes, Donna has minimal dialogue, while the Doctor delivers lengthy monologues. Donna’s engagement with the Library itself feels limited, and she often reverts to a more traditional, reactive companion role.

Candid cameras are everywhere even in Doctor Who Silence in the Library.

Candid cameras are everywhere even in Doctor Who Silence in the Library.

Donna expresses revulsion at the donated faces, prompting the Doctor to lecture her on relativism. She has two distinct “screaming companion” moments across the two episodes. The Doctor attempts to sideline her when matters become complicated at the end of Silence in the Library, a rare instance in Season 4 where Donna isn’t treated as the Doctor’s intellectual and emotional equal. Donna’s defining characteristic is her refusal to be silenced or dismissed by the Doctor’s technobabble.

Part of this issue might stem from episode scheduling. This is the final adventure featuring the Doctor and Donna before the companion-lite episodes leading into the season finale, which reunites nearly every major companion from the revived series. This was effectively the last opportunity to focus on the Doctor-Donna dynamic, making it disappointing that Moffat relegates Donna to the background and separates them in the second part.

Shadows play tricks in Doctor Who Silence in the Library.

Shadows play tricks in Doctor Who Silence in the Library.

Consequently, it feels like The Unicorn and the Wasp, episode seven of thirteen, was the last story to truly emphasize the Doctor and Donna as a team, creating a sense that their partnership diminished midway through the season. Given Season 4’s emphasis on their equal footing and the strong chemistry between Tate and Tennant, this feels like a missed opportunity.

Silence in the Library and Forest of the Dead are undeniably a mixed bag, with Forest of the Dead arguably being the weaker half. Yet, there’s considerable merit and resonance with the surrounding season. This marks Moffat’s final freelance Doctor Who story before assuming showrunner responsibilities, tasked with managing a massive multimedia franchise. The nostalgic atmosphere and the sense of revisiting familiar territory feel fittingly appropriate in this context.

Explore more of our reviews from David Tennant’s third season of Doctor Who: