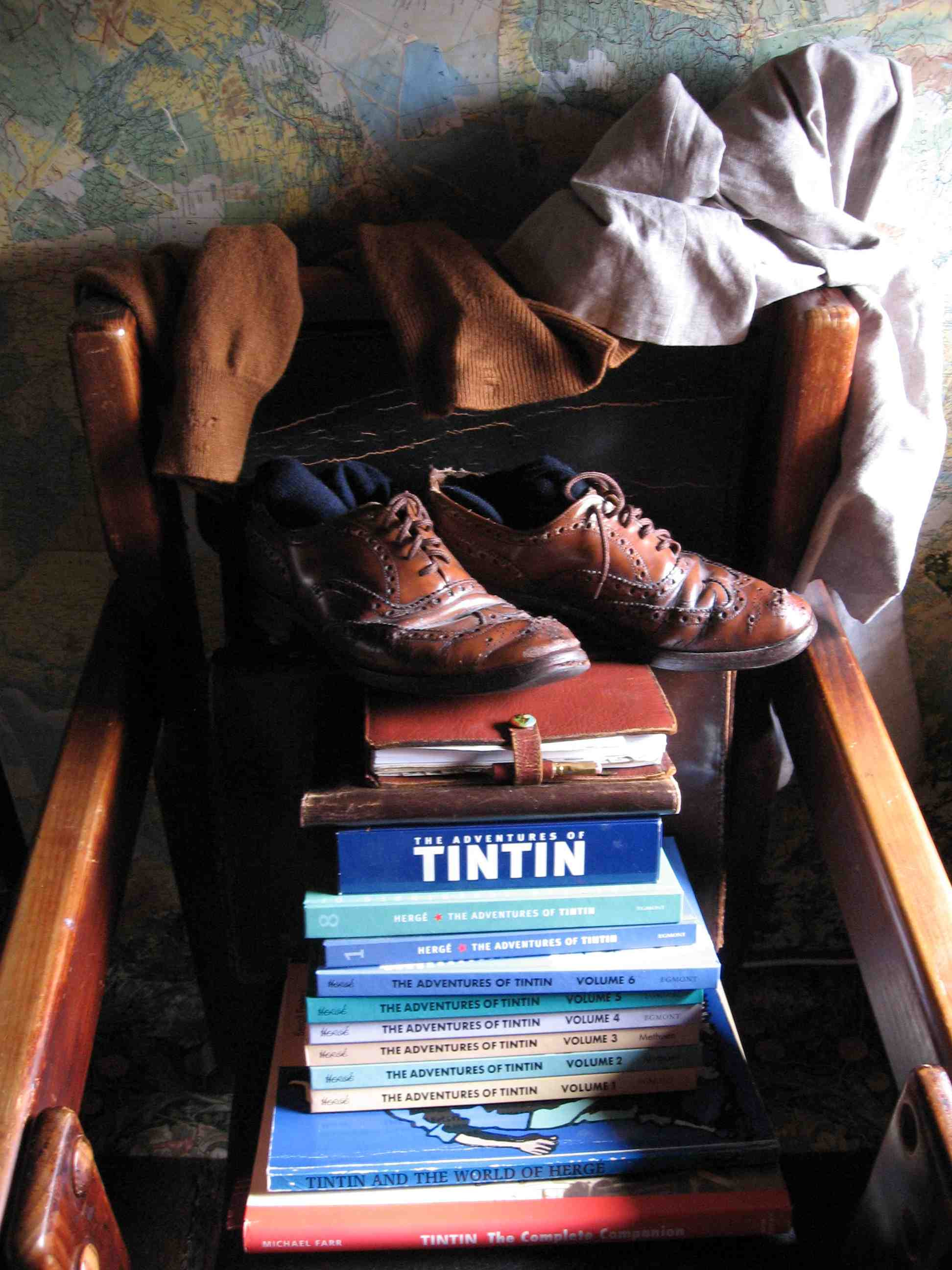

This article documents items from my comics art library research collection, focusing on the captivating world of comic books and graphic novels. Previously, I explored Hergé and his iconic creation, Tintin. My research collection includes a complete edition of the Tintin albums, the Tintin magazine Le Journal Des Jeunes De 7 A 77 Ans, and the Adventures of TINTIN DVD set. This exploration of Tintin and Franco-Belgian bande dessinée was a crucial step in my broader appreciation for the medium of comics, which naturally leads to considering other fascinating areas, such as the universe of Doctor Who Comics.

Tintin stuff (Art direction and photography-© 2013 Louise Graber)

Tintin stuff (Art direction and photography-© 2013 Louise Graber)

Assorted Tintin related materials from my collection, encompassing albums, appraisals, films, clothing, and studies, showcasing the breadth of the Tintin universe. (Art direction and photography-© 2013 Louise Graber)

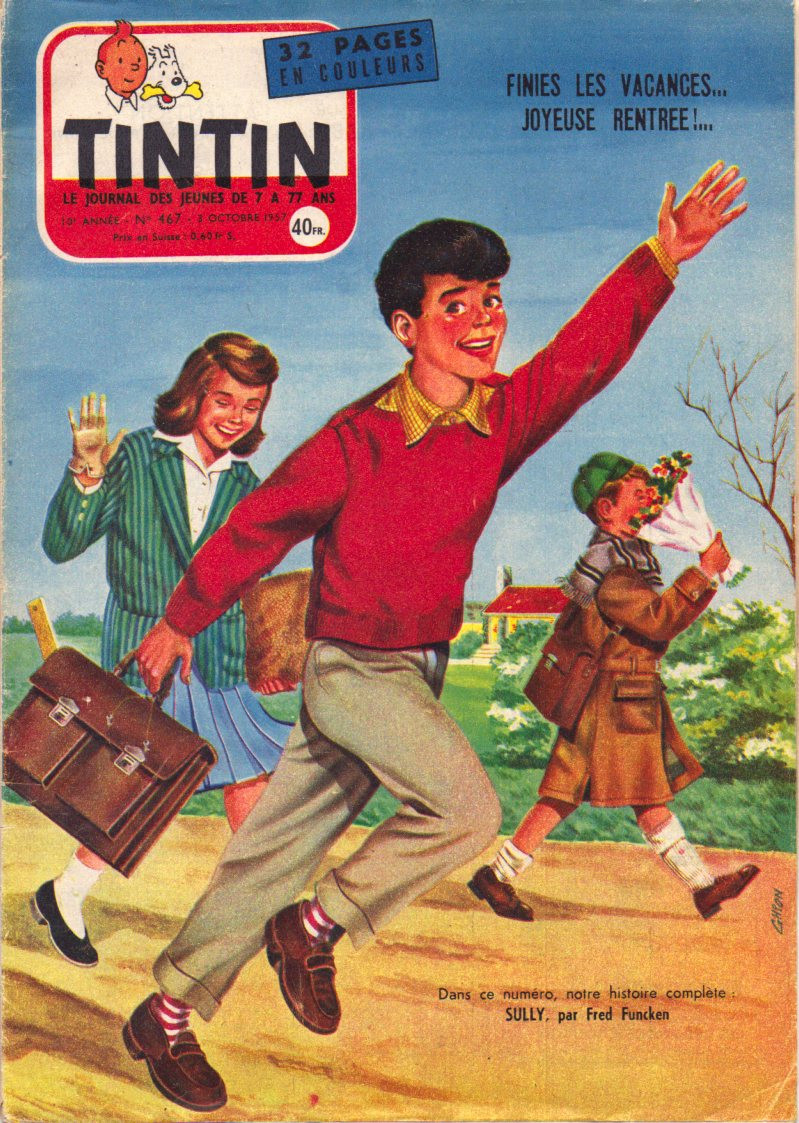

Tintin magazine, No. 467, October 1957.

Tintin magazine, No. 467, October 1957.

A vintage issue of Tintin magazine, No. 467, from October 1957, a window into the golden age of Franco-Belgian comics.

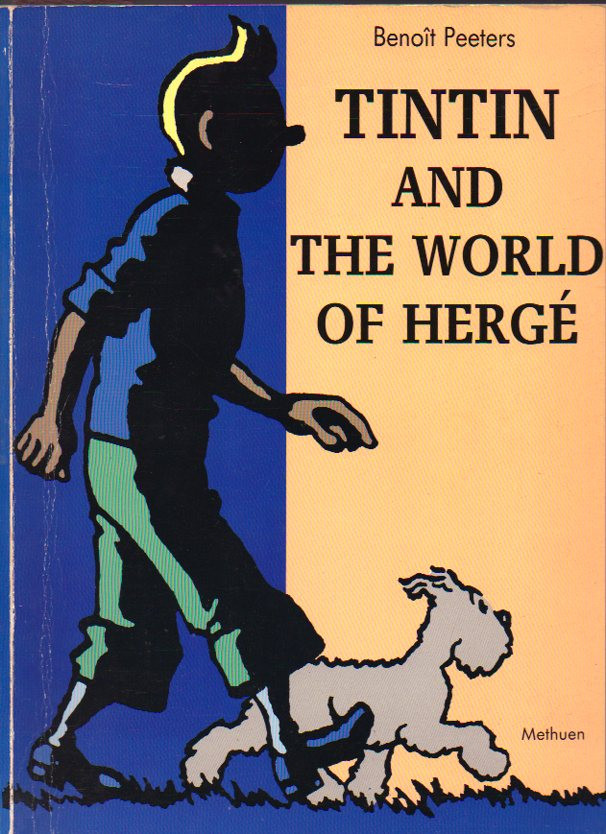

The Benoît Peeters study of Tintin and Hergé.

The Benoît Peeters study of Tintin and Hergé.

Benoît Peeters’ insightful study of Tintin and his creator Hergé, a critical analysis of a comics legend.

The Michael Farr Tintin companion book

The Michael Farr Tintin companion book

Michael Farr’s comprehensive companion book to Tintin, a guide for enthusiasts seeking deeper knowledge of the series.

The Adventures of Tintin albums, a collection of 24 stories including the final unfinished work, are renowned for their ligne claire (clear line) drawing style, a technique pioneered by Hergé and Edgar Pierre Jacobs. While I didn’t encounter these masterpieces in my childhood, my early exposure to comics was shaped by other influences. American comics by Carl Barks and Hank Ketcham, along with British “boys papers” like The Eagle, ignited my imagination. The Eagle, with its Dan Dare cover stories, sparked a fascination with space travel, and interestingly, also featured The Adventures Of Tintin episodes as a centre-spread. Another weekly, TIGER and Hurricane, featuring Roy of the Rovers, nurtured my early passion for football. My father’s reading habits, which included war and western comics and the comics section of the Sunday Mail newspaper, further fueled my burgeoning interest in this unique storytelling form. The combination of words and images in comics presented a captivating narrative experience.

My formal education, however, initially prioritized textual literacy. English lessons focused on words, often overshadowing accompanying illustrations. Consequently, when I first began reading comics, I instinctively prioritized captions and word balloons, often only glancing at the drawings afterwards. At times, I would even jump between panels, following the text and only cursorily observing the images. It took years to reverse this “upside down” approach and achieve a balanced appreciation for both words and images in comics. Eventually, I learned to perceive a comics page and individual panels holistically, integrating both visual and textual elements, sometimes even simultaneously. While this shift might have slightly impacted my linguistic skills, it undeniably enriched my artistic perception. Neither the Dominican nuns nor the Christian Brothers who educated me offered Art as a formal subject, leaving me to explore and develop my artistic inclinations independently.

An uncle, a reader of Western comics with a talent for sketching horses, hats, and guns, introduced me to basic sketching techniques. His guidance and my subsequent practice led to an incident in primary school. A sketch of Saint Therese ascending to Heaven as “the little flower,” intended as an illustration for a Religious Studies essay (though illustrations were not required), caused quite a stir, even bringing tears to the eyes of nuns. My submission was predominantly art, accompanied by a brief paragraph of text. This unexpected reaction, the nuns keeping my drawing, and the subsequent award of the Religious Studies prize (much to the surprise of the class valedictorian) provided a peculiar yet potent encouragement for my artistic pursuits.

My discovery of Tintin occurred later, during adolescence, coinciding with the publication of English translations. Libraries, surprisingly, became an unexpected source for these comics, a notable exception in an era when librarians seemed hesitant to include comics in their collections. Tintin, however, was often categorized as European narrative, pictorial albums, rather than comics, perhaps due to their hardcover format, distinguishing them from the softcover pamphlet style of North American comics. This perception, coupled with their foreign origin, seemingly rendered them more “book-like” and thus acceptable for library shelves.

And popular they were! Students avidly read and borrowed Tintin albums, often making them scarce on library shelves. Later, during tertiary studies and research, I systematically collected and read the entire Tintin series, appreciating the beautifully printed color drawings, the exotic locales, Captain Haddock’s amusing pronouncements, and the surprising amount of slapstick humor. These elements deepened my appreciation for bande dessinée and the broader realm of the Ninth Art. This appreciation solidified over time, culminating in a shift towards prioritizing the illustrations before the word balloons. The adoption of my Doctor Comics persona followed this immersive experience with comics. Later, I became aware of the unresolved and serious allegations of racism against Hergé, a complex aspect that possibly influenced his creative output. Some items from my Tintin collection are featured in this article, along with a published review I authored of a Tintin-themed art exhibition in Sydney. This journey through Tintin and European comics provided a strong foundation for exploring diverse genres and styles within the medium, naturally leading to an interest in science fiction comics and, specifically, the exciting world of Doctor Who comics.

A volume of the collected works in the reduced size format.

A volume of the collected works in the reduced size format.

Volume 8 of the TINTIN series in a compact, collected format, ideal for revisiting classic adventures.

Another Tintin study book-this one by Harry Thompson (no relation).

Another Tintin study book-this one by Harry Thompson (no relation).

Harry Thompson’s profile book on Tintin, offering another perspective on the character and his enduring legacy.

Doctor Comics encounters cartoon character friends in the Paris Metro, highlighting the global appeal of comics. (Photo by Louise Graber).

EXHIBITION REVIEW: Comic Strip, Passion’s Trip, Sydney, Alliance Francais de Sydney, November 18-December 20, 2002, review by Dr. Michael Hill (a.k.a. Doctor Comics), first published in International Journal of Comic Art, Vol.5 No.1 Spring/Summer 2003

The “Tintin” spirit, much like the Doctor’s TARDIS, seemed to materialize in Sydney in November 2002. While Tintin‘s Flight 714 in the comics took him to a scientific symposium in 1968, his cultural entourage arrived in Sydney decades later in the form of a Belgian comics exhibition, Comic Strip, Passion’s Trip. This exhibition, landing alongside a cargo of Belgian beer, chocolates, and comics, three quintessential Belgian exports, and accompanied by members of the Royal family, showcased the significance of Franco-Belgian comics on a global stage.

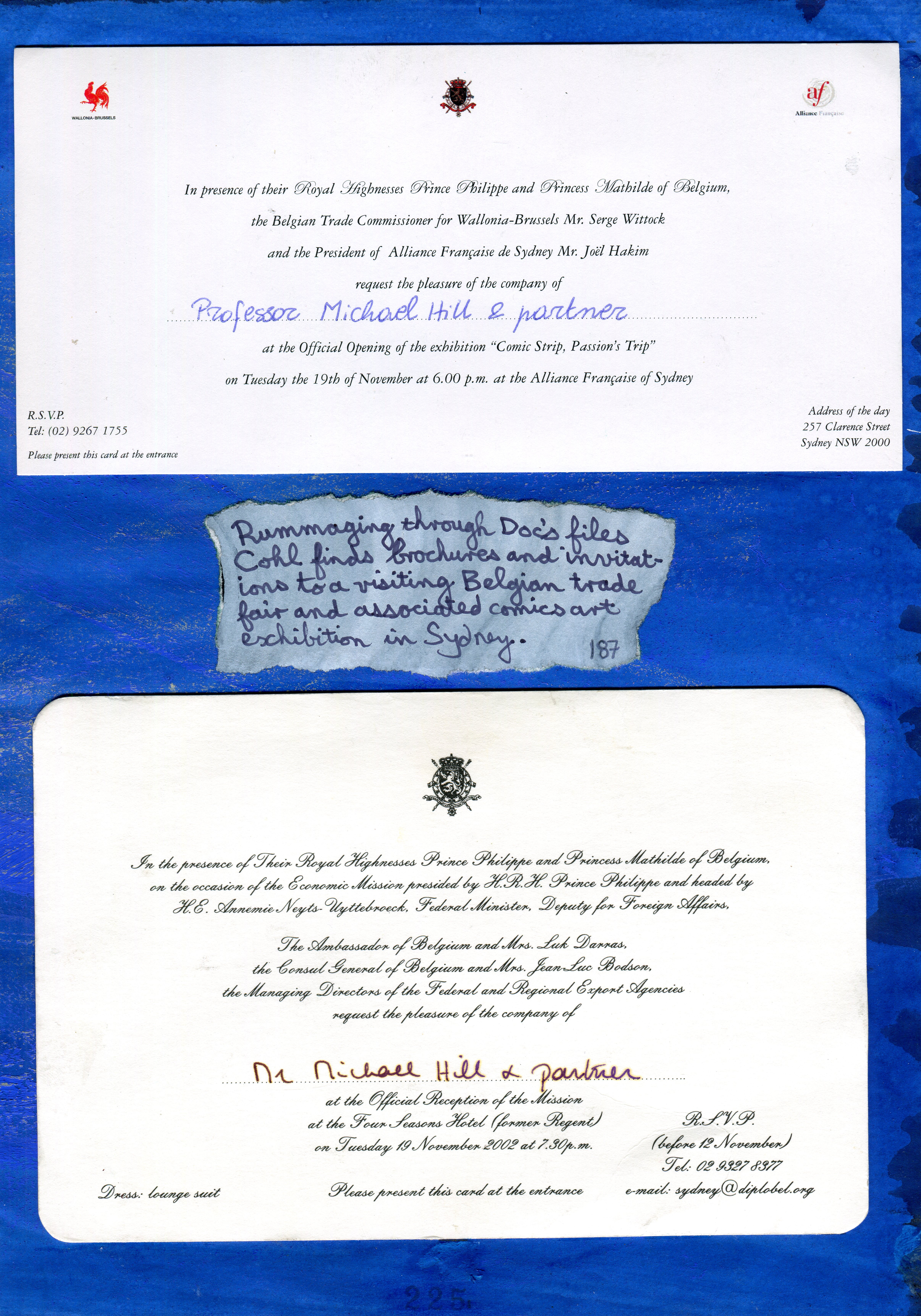

Belgium’s substantial comic exports, representing approximately 65% of their publication exports, underscore their national recognition of comics as the Ninth Art. The existence of a museum dedicated to comics in Belgium further solidifies this cultural importance. Therefore, the royal patronage at the exhibition opening, with Prince Philippe and Princess Mathilde in attendance, was a fitting endorsement. (Invitations to the exhibition opening and the subsequent Royal reception are depicted in my graphic novel BLOTTING PAPER, shown below). The exhibition was a part of an economic mission organized by the Wallonia-Brussels Sydney Trade Office, bringing 300 French comic titles and 70 English titles to Sydney. This initiative created a vibrant hub for European comics in the local market, introducing competition to the then-dominant Japanese manga and Hong Kong comics. Just as this exhibition highlighted the breadth of Belgian comics, one can imagine the potential for an exhibition dedicated to Doctor Who comics, showcasing its own rich history and diverse artistic interpretations across decades.

A page from my graphic novel BLOTTING PAPER: The Recollected Graphical Impressions of Doctor Comics, featuring invitations to the Belgian comics exhibition events.

The Comic Strip, Passion’s Trip exhibition was hosted at the Alliance Francais de Sydney, a venue combining gallery space, a café, and a French language center. Despite its bustling location near a city bus stop, the exhibition’s window display of vintage comics captivated passersby. A large model of André Franquin’s character Marsupilami added a playful, acrobatic element to the display. Curated by Jean-Marie Derscheid, the exhibition was thoughtfully designed with a multi-faceted approach, encompassing comic books, comics art, and the artistic process. A dedicated display recreated a comic artist’s studio, offering insights into the creative workflow. A child’s bedroom setting, adorned with comics merchandise, provided a whimsical touch. Videos and an oversized mock-up comics album (82cm x 56cm), beautifully bound and designed, contextualized Belgian comics, featuring concise biographies and examples from 20 notable artists. These artists included Didier Comes, André Franquin, Greg, Hergé, Hermann Huppen, Edgar Pierre Jacobs, Jijie, Lambil, Raymond Macherot, Morris, Peyo, Francois Schuiten, Jean-Claude Servais, Tibet, Maurice Tillieux, Tome and Janry, Will, and Yslaire. References to Spirou magazine and the influential Brussels and Marcinelle schools of comics further enriched the exhibition’s context.

The child’s bedroom installation featured a Tintin themed doona cover and bed sheets, alongside a Gaston Lagaffe reading lamp by André Franquin and a Marsupilami alarm clock. Posters and a cupboard filled with Lucky Luke figurines completed the scene. Notably absent was a Smurf! A small television with a video player showcased Belgian animated cartoon series. Humorously, by the exhibition’s opening night’s end, the child’s room was amusingly cluttered with empty beer bottles, left by appreciative guests, creating a bizarre visual association between beer and comics in a nursery setting – a scene that Doctor Comics would certainly have appreciated. He champions the combination of “beer, chocolate and comics!” as an ideal indulgence.

Another exhibition section showcased individual displays dedicated to specific artists, including Hermann, Geerts, Midam, Yslaire, Morris, Jacobs, Herge, Francois and Luc Schuiten, Francqu and Van Hamme, Dufaux and Marini, Lambil, Marc Bnoyninx, Tome and Janry, Constant and Vandamme. Original artwork and accessible copies of comics albums, though showing signs of enthusiastic readership by the exhibition’s end, were also available.

Upstairs, a seminar room hosted a mock-up ‘artist’s studio.’ Large photographs depicted the workspaces of various comic creators. A drawing table with pencils and equipment was set up, and a video corner screened a documentary on the artist Frank, showcasing his work on The Source, a comic book about Australia commissioned for the exhibition. Frank’s watercolour sketches of Australian animals were impressive. Despite his first visit to Australia coinciding with the exhibition opening, his comic depicted the desert landscape. While his color palette was accurate, some conceptual elements were culturally insensitive, particularly his depiction of Uluru (formerly Ayers Rock), a site of immense cultural significance to its indigenous owners. The exhibition brochure itself, perhaps aware of this potential misstep, tongue-in-cheekly referenced “our delightfully cliched images of Australia: kangaroos, boomerangs, mythical Aborigines and smouldering red deserts.” Despite this, the exhibition’s overall achievement was in highlighting comics as a significant cultural art form, valued and collected by libraries and museums – a celebration of the high regard for comics art in Belgium. This dedication to showcasing comics as art is something that could equally benefit the appreciation and understanding of Doctor Who comics and their contribution to the broader comics landscape. Imagine an exhibition exploring the evolution of Doctor Who comics art, from early adaptations to modern interpretations, showcasing the diverse artists and writers who have contributed to this universe.