In an era marked by groundbreaking technological advancements and a growing demand for accessible healthcare, the early 20th century also witnessed the rise of medical quackery. Among the most notorious figures in this shadowy realm was John Brinkley, a man who, despite questionable medical credentials and outlandish treatments, became a household name. Doctor Brinkley, as he styled himself, amassed a fortune by implanting goat testicles into men seeking a cure for sexual dysfunction and the effects of aging. His story is a compelling, if disturbing, example of how public desire for quick fixes, combined with savvy marketing and political maneuvering, can elevate even the most dubious practitioners to prominence. Brinkley’s career, spanning over two decades, reveals the enduring allure of panaceas and the persistent challenge of distinguishing genuine medical expertise from deceptive charlatanism.

Keywords: History of Medicine, Quackery, Medical Charlatan, Radio Broadcasting, Doctor Brinkley

Born in 1885 in the impoverished Appalachian region of North Carolina, John R. Brinkley experienced a difficult childhood, orphaned at a young age and raised by his aunt and uncle.1 His early life provided little indication of the flamboyant and controversial figure he would become. Before venturing into medicine, Brinkley’s entrepreneurial spirit led him to the world of entertainment. In 1907, at the age of 22, he and his first wife embarked on a medicine show circuit. This traveling spectacle combined song and dance performances with the hawking of homemade tonics and remedies.2 This experience proved formative, teaching Brinkley valuable lessons in salesmanship and audience engagement. He learned to connect with the public by tapping into their values and anxieties, and discovered the effectiveness of portraying mainstream doctors as out-of-touch and self-serving.1 These tactics resonated strongly in the early 20th century, a time when the scientific basis of conventional medical treatments was often not much stronger than the claims made by traveling medicine shows.2

After his stint on the medicine show circuit, Brinkley sought to legitimize his medical ambitions, at least superficially. He moved to Chicago and enrolled in Bennett Medical College, one of the “eclectic” medical schools prevalent at the time. These institutions focused on botanical remedies and represented a less orthodox approach to medicine compared to the emerging scientific model. However, Brinkley’s formal medical education was short-lived. Unable to afford tuition, he dropped out of Bennett Medical College without obtaining a degree. 1,3 For several years, he drifted across the country, reportedly evading creditors and engaging in various occupations. During this period of wandering, he briefly worked at a slaughterhouse where his fascination with goats began, intrigued by their apparent robustness and resistance to diseases that afflicted humans.3 His personal life was also tumultuous; he separated from his first wife and entered into a second marriage with Minnie Telitha, without formally divorcing his first spouse.

Despite his lack of conventional medical training, Brinkley managed to acquire a medical degree from the Eclectic Medical College of Kansas City. This institution, like Bennett, was considered a less rigorous “eclectic” school. While some have argued that his education was comparable to many physicians of that era, given the then-lax standards of medical education,1 it’s important to note the significant reforms and increasing emphasis on scientific rigor that the medical field was undergoing. Armed with his degree, Doctor Brinkley responded to an advertisement from the rural town of Milford, Kansas, seeking a family physician, marking the beginning of his infamous medical practice.

1. The Infamous Goat Gland Operation of Doctor Brinkley

In 1917, Doctor Brinkley arrived in Milford, Kansas, and established himself as the town’s physician. Initially, his practice seemed conventional. When the Spanish flu pandemic reached Milford, he earned local respect for his dedicated care of the afflicted.4 However, his practice soon took a dramatic and unconventional turn. He was consulted by an elderly farmer struggling with infertility, seeking to father another child. Drawing upon his earlier fascination with the perceived vitality of goats, Doctor Brinkley proposed a radical solution: surgical implantation of goat testicles to restore the farmer’s virility. The farmer, eager for a remedy, agreed. The results, as reported, were deemed successful by the patient, though the exact reasons remain unspecified and are likely attributable to placebo effects. Word of this “miraculous” treatment spread rapidly in Milford, leading to another patient, William Stittsworth. Stittsworth requested the goat gland operation for himself and, remarkably, also requested goat ovaries be implanted into his wife.1 Within a year, the Stittsworths had a son, named “Billy,” further fueling the legend of Doctor Brinkley’s goat gland miracle. 1 (Fig. 1) Doctor Brinkley performed the procedure on more patients, reportedly receiving overwhelmingly positive feedback. At the peak of his goat gland practice, he charged a hefty $750 per operation, equivalent to over $10,000 in today’s currency.2,5

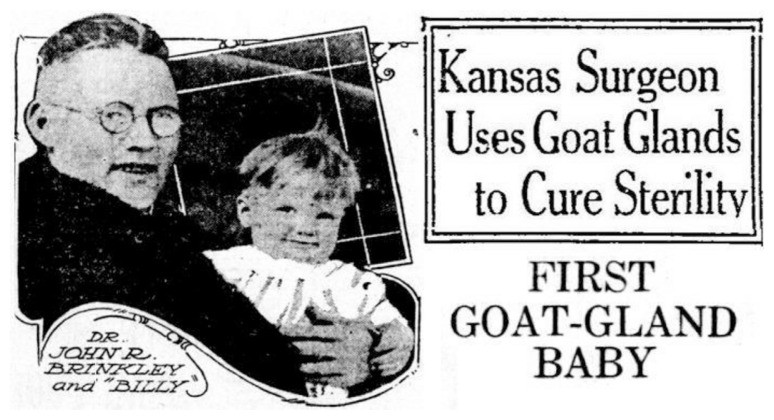

Fig. 1. Doctor Brinkley’s Clinic Advertisement, 1920s.

This vintage newspaper ad showcases Doctor Brinkley proudly posing with Billy Stittsworth. Billy’s birth was attributed to Doctor Brinkley’s second xenotransplantation procedure performed on his father, highlighting the sensational claims surrounding his goat gland operations. Image courtesy of Wikimedia Commons.

Recognizing the immense potential of his unorthodox treatment, Doctor Brinkley hired an advertising consultant to promote his procedure nationwide. The sensational story captured the attention of prominent figures, including J. J. Tobias, chancellor of the University of Chicago Law School. Tobias traveled to Milford to undergo Doctor Brinkley’s goat gland surgery. His testimonial was effusive: “I was played out … I was an old man. I went to Milford and underwent Doctor Brinkley’s operation … Four days later the headaches disappeared … And seven days later I left the hospital feeling twenty-five years younger. And I seem to grow still younger every day.”3

Another influential convert was Harry Chandler, owner of the Los Angeles Times and KHJ, Los Angeles’s pioneering radio station. Chandler invited Doctor Brinkley to California for the procedure, reporting similarly positive results. Chandler used his media platform to publicly praise Doctor Brinkley’s goat gland operation.5 These high-profile endorsements from Tobias and Chandler unleashed a torrent of patients, fame, and wealth upon Doctor Brinkley, enabling him to establish his own hospital in Milford, solidifying his position as a medical entrepreneur.

It’s important to note that the concept of xenotransplantation, transplanting animal tissue into humans, wasn’t entirely fringe in Doctor Brinkley’s time. Some mainstream physicians believed in its potential.1 Early attempts at animal blood transfusions and skin grafts dated back to the 17th century, and a pig cornea transplant was performed in 1838.6 French surgeon Serge Voronoff gained international recognition in the early 20th century for transplanting ape testicles into humans.1,6 While modern medical science dismisses these early efforts as misguided,6 they did generate considerable interest, even within the established medical community of the time. In 1922, Doctor Brinkley self-published a book promoting his procedure, boldly claiming, “today I am able to announce to the world, without mincing words, that the right method has been found, that I am daily transplanting animal glands into human bodies, and that these transplanted glands continue to function as live tissue in the human body, revitalizing … the human gland.”7

The question remains: did Doctor Brinkley’s goat gland operation offer any real medical benefit, or were the reported improvements simply placebo effects? Could the implanted goat testicles, even if rejected by the body, have released hormones or other substances that temporarily enhanced well-being or fertility? While highly improbable, these possibilities have never been rigorously investigated scientifically. Regardless of the physiological mechanisms, or lack thereof, Doctor Brinkley’s goat gland operation became his signature treatment, propelling him to national notoriety.

2. Radio, Celebrity Status, and Battles with the Medical Establishment

Doctor Brinkley’s California sojourn, facilitated by Harry Chandler, exposed him to the burgeoning power of radio broadcasting. Recognizing its potential for reaching a vast audience, in 1923, he established his own radio station in Milford, KFKB (Kansas First, Kansas Best). KFKB quickly became one of the most popular radio stations in America,8 a testament to Doctor Brinkley’s astute programming. The station’s format was a diverse mix of “country music, comedy, poetry readings, market news, weather reports,… orchestras, and gospel preaching.”1 This eclectic programming appealed to rural audiences, but the station’s unique draw was Doctor Brinkley himself, who hosted twice-daily medical talks. These programs, titled Medical Question Box, ostensibly addressed health concerns but primarily served to promote Doctor Brinkley’s hospital and medical procedures. Remarkably for the era, Medical Question Box frequently tackled topics related to sexuality, establishing Doctor Brinkley as a sort of proto-“Dr. Ruth Westheimer of the twenties and thirties.”9 His radio broadcasts fostered a sense of trust and personal connection with his listeners, driving thousands to seek treatment at his Milford hospital.

Doctor Brinkley further expanded his medical enterprise into pharmaceuticals, creating a network of pharmacies that promoted his patent medicines. He prescribed medications over the radio, encouraging listeners to self-diagnose and self-treat based on his broadcasts. This blatant disregard for established medical practices and patient safety alarmed the mainstream medical community, raising serious concerns about the dangers posed by Doctor Brinkley’s unregulated activities.1

As Doctor Brinkley’s fame and fortune grew, so did scrutiny of his methods, particularly amidst growing national awareness of the deficient standards of many North American medical schools. In 1923, newspapers launched investigations into eclectic medical colleges, including Doctor Brinkley’s alma maters, alleging they were essentially diploma mills selling degrees with minimal academic requirements. That same year, California attempted to arrest Doctor Brinkley for practicing medicine without proper credentials. However, the Governor of Kansas, a political ally of Doctor Brinkley, refused extradition. Undeterred, the Kansas City Star10 newspaper began publishing exposés detailing the experiences of dissatisfied patients, further eroding Doctor Brinkley’s credibility in some circles.

Meanwhile, Morris Fishbein, the influential editor of the Journal of the American Medical Association (JAMA), spearheaded a determined campaign against medical quackery. In a 1928 JAMA article, Fishbein directly challenged Doctor Brinkley’s medical credentials, pointing out inconsistencies in his claimed educational timeline.11 In April 1930, Fishbein escalated his attack, branding Doctor Brinkley in another JAMA editorial as “a charlatan of the rankest sort” who was using his radio station to “victimize people and to enrich himself.”1 Medical societies in Kansas joined Fishbein’s crusade, initiating proceedings to revoke Doctor Brinkley’s medical license. Doctor Brinkley retaliated via KFKB, vowing to produce ten satisfied patients for every dissatisfied one presented by his medical adversaries.1

In 1930, Doctor Brinkley faced the Kansas Medical Board on eleven formal charges, including misrepresenting his educational qualifications and improperly prescribing treatments via radio without patient examination or proper diagnostic testing.1 Doctor Brinkley’s defense attempted to deflect criticism by highlighting an article by Fishbein that ironically “predicted that the doctor of the future would never have direct contact with patients, but would sit behind a large desk while diagnosing and prescribing over the television, much like John Brinkley was doing with his Medical Question Box on the radio.”1 Doctor Brinkley even invited board members to observe his surgical skills firsthand. One board member, impressed by Doctor Brinkley’s technical dexterity, described his surgical demonstration as “as skillful and deft a demonstration of surgery as he had ever witnessed.”1 Despite this, Doctor Brinkley’s surgical ability wasn’t enough to save his license. In September 1930, the Kansas Medical Board revoked Doctor Brinkley’s medical license for “gross immorality” and “unprofessional conduct.”1 Concurrently, KFKB’s radio license was also revoked, forcing the station off the air in February 1931.12 However, this was not the end of the Doctor Brinkley saga. His licensed associates continued performing his goat gland operation at his Milford hospital. Paradoxically, the hearings before the Kansas Medical Board, and the ensuing media attention, inadvertently boosted Doctor Brinkley’s business by casting him as a persecuted outsider. Many Kansans rallied to his defense, distrusting the “establishment” figures attacking him from afar.

The outpouring of support following the license revocation included numerous calls for Doctor Brinkley to run for Governor. Just five days after losing his medical license, he announced his candidacy as an independent, write-in candidate. His political platform resonated with populist sentiment, emphasizing “fearlessness, independence, [and] sympathy for the masses,”13 appealing to those suffering from the economic hardships of the Great Depression. He advocated for workers’ compensation, child labor laws, free medical care for the poor, and pensions for the elderly and disabled – many of these proposals foreshadowed Franklin D. Roosevelt’s New Deal.14

In a controversial move during the election campaign, reminiscent of later political tactics regarding voting technicalities, the Kansas Attorney General declared that write-in votes for Doctor Brinkley would only be counted if written precisely as “J. R. Brinkley,” disallowing any variations. This deviated from past practice where voter intent was the primary consideration.15 Despite this obstacle, Doctor Brinkley garnered over 183,000 votes in a record turnout election, finishing a close third. It is estimated that as many as 50,000 votes were disqualified due to improper name format, potentially enough to have swung the election in Doctor Brinkley’s favor.1 Doctor Brinkley chose not to contest the election results, setting his sights on a repeat gubernatorial bid in 1932 (Fig. 2), which again resulted in a narrow third-place defeat.

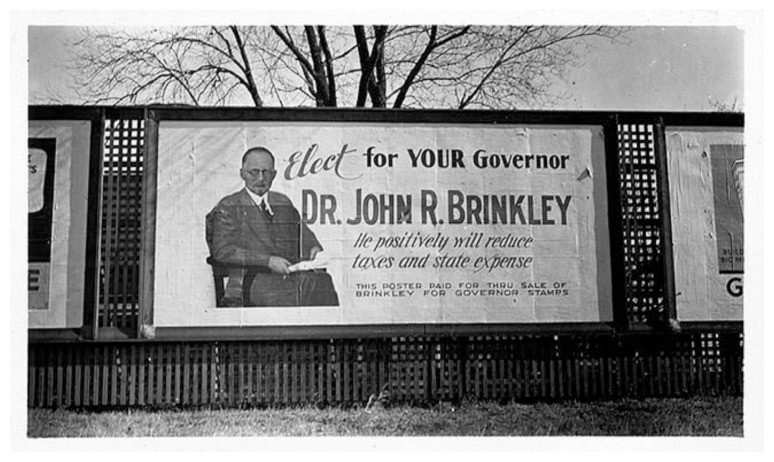

Fig. 2. Doctor John R. Brinkley Gubernatorial Campaign Poster, 1932.

This campaign billboard from Doctor Brinkley’s second gubernatorial run in 1932 highlights his carefully crafted public image as both a medical professional and a populist champion, promising tax reduction. Photograph by J. T. Williard, from https://krex.k-state.edu/dspace/handle/2097/37099.

3. Exodus from Kansas and Doctor Brinkley’s Downfall

Following the loss of KFKB, Doctor Brinkley relocated to Mexico and constructed a powerful new radio station, XER, in Villa Acuña, just across the border from Del Rio, Texas. In late 1932, he moved to Del Rio permanently to be closer to his radio empire and to leverage his still-valid Texas medical license to continue his medical practice. In Del Rio, Doctor Brinkley’s practice thrived, generating an annual income exceeding one million dollars.

Around 1933, Doctor Brinkley subtly shifted his medical focus to the prostate gland, which he famously dubbed the “troublesome old cocklebur.”16 He abandoned the goat testicle implant in favor of a procedure resembling a unilateral vasectomy, which he claimed effectively treated prostate problems. This surgical procedure was accompanied by a series of six post-operative injections of “Formula 1020.” Analysis revealed “Formula 1020” to be nothing more than a diluted solution of blue dye in water. Morris Fishbein sarcastically described its manufacture as “raking a body of water like Lake Erie, coloring it with a dash of bluing and then selling the stuff at $100 for six ampules.”17

Doctor Brinkley’s new prostate surgery made him more vulnerable to patient complaints. Patients seeking rejuvenation through goat gland implants might have been hesitant to complain about sexual dysfunction, but, as Fishbein astutely observed, “men do not have the same hesitancy about discussing operations for the relief of pathological conditions of the prostate than they do in talking about sexual rejuvenation.”1

In 1938, Doctor Brinkley moved again, this time to Arkansas, a state with a reputation for lenient medical licensing, where several of his associates had obtained licenses.16 Shortly after his move, Fishbein published a scathing article in Hygeia, a health magazine published by the AMA, denouncing Doctor Brinkley as the epitome of “quackery [that had] reached its apotheosis.” He further asserted that Doctor Brinkley possessed “consummate gall beyond anything revealed by any other charlatan … [in] shaking the shekels from the pockets of credulous Americans.”1 Doctor Brinkley, perhaps overconfident, decided to sue Fishbein for libel, a decision that proved disastrous. In the ensuing libel trial, Fishbein’s attorney skillfully cornered Doctor Brinkley into admitting under oath that he knew the goat gland operation “did not and could not rejuvenate a man by itself and that his advertisements claiming this ability during the previous decade were false.”1 Fishbein’s attorney further argued that “Doctor Brinkley is the foremost money-making surgeon in the world because he had sense enough to know the weaknesses of human nature and gall enough to make a million dollars a year out of it.”1 The jury sided with Fishbein, delivering a decisive verdict against Doctor Brinkley. Doctor Brinkley’s appeals failed, with the appellate court concluding that “the plaintiff by his methods violated acceptable standards of medical ethics—the plaintiff should be considered a charlatan and a quack in the ordinary, well-understood meaning of those words.”1

The repercussions of this legal defeat were immediate and devastating for Doctor Brinkley. The Fishbein libel case officially branded him a charlatan, triggering a cascade of malpractice lawsuits seeking over $3 million in damages. Doctor Brinkley returned to Del Rio, but his financial troubles and legal battles continued to escalate. The Mexican government confiscated his radio station, and in February 1941, he declared bankruptcy. In September 1941, a grand jury in Little Rock indicted Doctor Brinkley, his wife, and six associates on mail fraud charges, to which his wife and associates pleaded no contest. Doctor Brinkley’s trial was postponed due to his declining health. His health deteriorated rapidly, and he died on May 26, 1942, never facing legal accountability for his decades of medical quackery, despite amassing a vast fortune.

4. Doctor Brinkley’s Dubious Legacy

John R. Brinkley is rightfully remembered as a quack, “an ignorant or fraudulent pretender to medical skill,”1 who prioritized personal enrichment over his patients’ well-being. Yet, in a perverse way, he was a significant figure in the history of medicine and media. He brought attention to previously neglected areas of men’s health – aging and sexual decline in older men. Even though he knew his treatments were ineffective, he reportedly performed them with surgical skill and patient care comparable to, or even exceeding, some reputable doctors of his time. Furthermore, Doctor Brinkley pioneered the use of mass communication in healthcare, arguably becoming the first “radio doctor” to provide medical advice to a broad public audience. Even his harshest critics acknowledged his talents as a surgeon, communicator, and businessman. Had Doctor Brinkley channeled his considerable abilities into ethical and legitimate medical practices, he might have made genuine contributions to medicine, rather than pursuing wealth at the expense of vulnerable patients.1 His story serves as a cautionary tale about the enduring appeal of medical quackery and the critical importance of evidence-based medicine and ethical medical practice.

Acknowledgements

Production of this manuscript was supported by NIH Grant #1F30HL145901 to PCS.

I thank Dr. Phil Mackowiak, MD, Professor Emeritus of Medicine at University of Maryland School of Medicine, for his help in editing the manuscript.

Footnotes

Conflicts of interest

The author denies any conflicts of interest.

Fig. 2

Fig. 2