Doctor Who, much like the horror genre’s slasher sub-genre, has cultivated a significant LGBTQI+ fanbase over its decades-long history. But what are the reasons behind this strong connection? While overt representation in the TARDIS was scarce until the show’s revival in 2005, the original series (1963-1989) presented a different landscape. Even simple acts like the Doctor hugging companions were discouraged, lest it hint at any romantic undertones within the iconic Police Box.

Despite the historical limitations, Doctor Who has introduced companions and characters who identify as openly gay or possess fluid sexualities, such as Captain Jack Harkness, River Song, Jenny, Vastra, Clara Oswald, Bill Potts, and Yasmin Khan. There’s even speculation about Ace’s bisexuality towards the end of the classic era. However, given the relative rarity of openly LGBTQI+ supporting characters, the question remains: why does Doctor Who resonate so deeply with the LGBTQI+ community?

This exploration aims to examine Doctor Who through an LGBTQI+ lens, uncovering aspects of the show that might have been previously overlooked. It’s not about imposing a particular viewpoint, but rather opening a dialogue and inviting readers to consider different perspectives on this beloved series.

Early Days: Subtext and Shifting Societal Norms

To understand the LGBTQI+ appeal of Doctor Who, we must journey back to the show’s beginnings in 1963. The United Kingdom of that era was vastly different, with same-sex relationships between men still illegal. Even after decriminalization in 1967, many individuals working behind the scenes in television, including Doctor Who, had to conceal their identities.

One such figure was Waris Hussein, the director of the very first Doctor Who serial, An Unearthly Child, and later Marco Polo. Hussein, whose sexuality was known to original producer Verity Lambert, explained that Doctor Who was initially conceived as a children’s adventure series. Discussions surrounding LGBTQI+ themes were not as prevalent as they are today, and incorporating such conversations directly into the narratives was simply not considered.

However, Hussein noted that there were opportunities for character interpretation. He pointed to Tegana, the villain in Marco Polo, clad in tight black leather with slicked-back hair, as a figure who, in contrast to the conventional masculinity of Mark Eden’s Marco Polo, could have resonated as a fantasy figure for some gay viewers at the time. For Hussein, this type of subtle subtext was the only avenue for LGBTQI+ themes in the early days of Doctor Who.

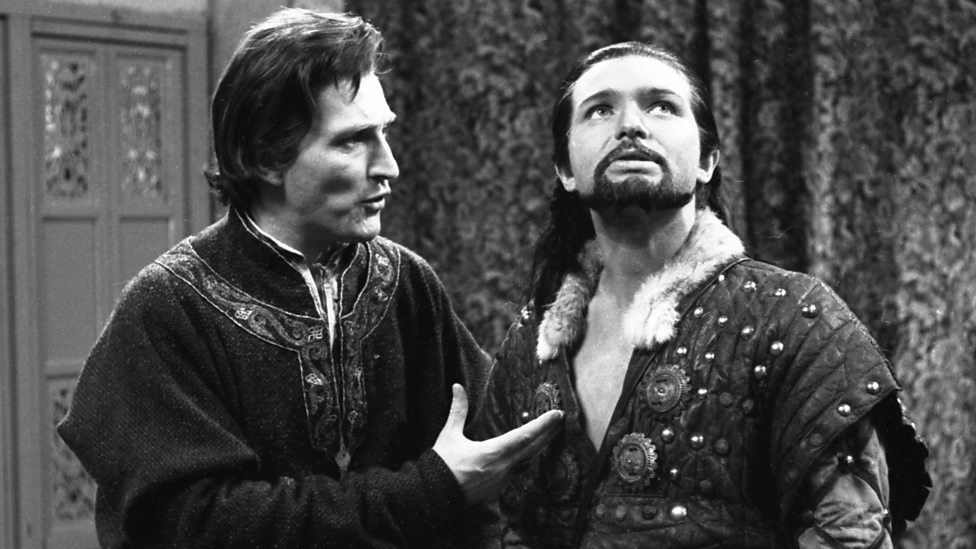

Actor Max Adrian as King Priam in *The Myth Makers*

Actor Max Adrian as King Priam in *The Myth Makers*

In 1965, actor Max Adrian guest-starred as King Priam in The Myth Makers. Adrian was openly gay and had faced legal persecution in 1940 for “importuning,” a charge used to target gay men at the time. Even a misinterpreted smile could lead to such charges, and Adrian served three months in prison. Regrettably, accounts suggest that William Hartnell, the First Doctor, treated Adrian poorly on set due to his sexuality. While not excusing such behavior, it’s crucial to remember the vastly different societal attitudes of 1908, Hartnell’s birth year, compared to the rapidly changing 1960s. Clashes regarding sexuality were, unfortunately, almost inevitable.

The Daleks and Cybermen: Mirrors to Societal Prejudice

While overt LGBTQI+ characters were absent, the early Doctor Who era offered allegorical representations that resonated with marginalized communities. Consider the second serial ever aired, The Daleks, introducing the Doctor’s most iconic adversaries. Premiering less than two decades after the end of World War II, the image of the Daleks, with their chilling cry of “Exterminate,” would have been particularly resonant. The Nazis’ attempted extermination of those deemed “different” was still a fresh wound in the collective memory.

Beyond the Daleks, the serial also featured the Thals, cousins of the Kaleds (an anagram of Daleks), whom the Daleks sought to annihilate simply for being different. The Doctor’s unwavering defense of the Thals underscored a core principle of the character and the show: justice and respect for all life in the universe. This inherent sense of fairness, present even when direct LGBTQI+ representation was impossible, is likely a key factor in the show’s broad appeal across diverse communities.

The Daleks in their debut *Doctor Who* serial

The Daleks in their debut *Doctor Who* serial

The Daleks’ xenophobia and desire to exterminate anything unlike themselves can be powerfully interpreted as a reflection of the prejudice faced by LGBTQI+ communities. Their Nazi origins and anti-Semitic inspirations are far from subtle. Indeed, anti-fascist themes were prevalent in British television throughout the 1960s and 70s, and the Daleks served as a potent symbol of fascist ideologies. They became a vehicle for teaching viewers about the dangers of such hateful ideologies.

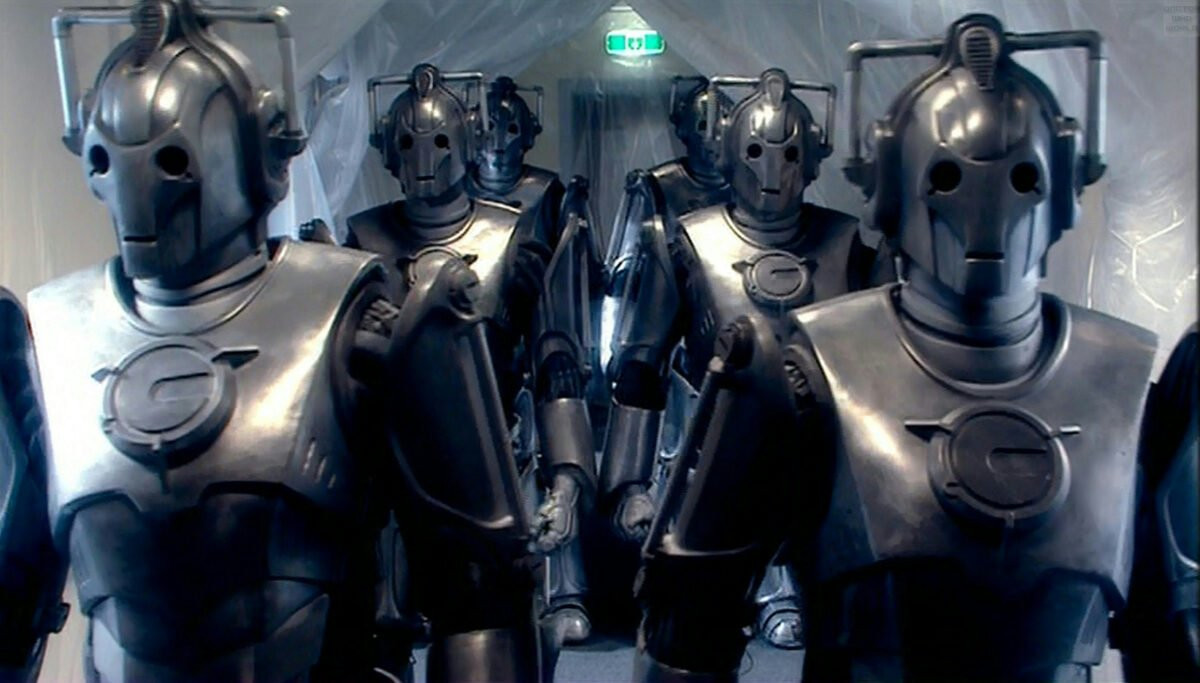

The Cybermen, introduced later, offer another layer of allegorical interpretation. While the Daleks represent blatant racism, the Cybermen’s desire for uniformity and forced conversion is arguably even more insidious. Their chilling mantra, “You Will Be Like Us,” from The Tomb of the Cybermen, encapsulates this terrifying concept.

In Doomsday, a Cyberman declaration further emphasizes this chilling ideology:

“Cybermen now occupy every landmass on this planet. But you need not fear. Cybermen will remove fear. Cybermen will remove sex and class, colour and creed. You will become identical. You will become like us.”

This desire to eradicate individuality is profoundly disturbing. The idea of becoming a emotionless, metallicized automaton is a stark metaphor for the suppression of identity and the erasure of difference. While the Daleks embody fascism, the Cybermen can be seen as representing a twisted form of enforced equality, a perversion of communist ideals taken to an extreme. This chilling vision of a homogenous universe, devoid of individual expression, stands in stark contrast to the vibrant diversity that LGBTQI+ communities champion.

Cybermen in *Doomsday*

Cybermen in *Doomsday*

Individualism is paramount to the survival and flourishing of LGBTQI+ communities. The Cybermen’s ideology, the forced conformity to societal norms, unfortunately, still resonates in many parts of the world where LGBTQI+ rights are suppressed. This struggle against enforced conformity, mirrored in the Cybermen’s relentless conversion, continues to be a relevant and potent theme for LGBTQI+ viewers. The seeds of bigotry and prejudice, like the Cybermen’s ideology, remain a persistent threat.

Subtle Shifts and Camp Sensibilities: The 70s and 80s

The legal landscape began to shift in 1967 with the decriminalization of same-sex relationships between men in the UK. However, Doctor Who‘s commitment to justice and inclusivity remained consistent, regardless of societal changes. While the 1970s might appear devoid of overt LGBTQI+ representation, subtle hints and character interpretations emerged.

Liz Shaw, introduced in Spearhead from Space, became the Third Doctor’s companion. A brilliant and independent scientist working for UNIT, Liz, in line with Waris Hussein’s earlier observations, existed in an era where overt LGBTQI+ themes were still largely absent from mainstream television. However, the “Wilderness Years” of the 1990s, when Doctor Who was off the air, saw a series of direct-to-video films by Mark Gatiss featuring Liz Shaw working for PROBE. These films not only included Doctor Who‘s first same-sex kiss between two men within the show’s continuity but also depicted Liz in a relationship with her female boss, Patricia Haggard, in the 2014 film PROBE: When to Die. This made Liz Shaw the first on-screen companion to be explicitly portrayed as gay.

Caroline John as Liz Shaw in *Doctor Who*

Caroline John as Liz Shaw in *Doctor Who*

A famous line from City of Death, where the Fourth Doctor tells the Countess, “well, you’re a beautiful woman – probably,” has been interpreted by some fans as hinting at the Doctor’s asexuality. This interpretation aligns with the producers’ reluctance to depict the Doctor as overly affectionate with companions, fearing romantic misinterpretations. Whether intended or not, this line and the Doctor’s general detachment could resonate with asexual viewers. However, many also see the line as simply an example of the Doctor’s quirky and cheeky personality.

By the 1980s, Doctor Who embraced a more overtly camp aesthetic. Under producer John Nathan-Turner, the show became brighter, more colorful, and incorporated stunt casting, contributing to a camp sensibility that likely appealed to LGBTQI+ viewers. The Rani’s line in Time and the Rani, “Leave the girl, it’s the man I want,” became a favorite among fans and a recurring quote at conventions.

Fourth and Fifth Doctor companion Adric, played by openly gay actor Matthew Waterhouse (though not publicly known at the time), was later confirmed in an audiobook, A Full Life, to be bisexual, having been married to both a woman and a man. The restrictive broadcasting environment, influenced by American laws prohibiting positive portrayals of homosexuality, prevented any overt exploration of Adric’s sexuality on screen. Looking back, Adric’s death might be interpreted through a modern lens as a way to avoid depicting a potentially LGBTQI+ character in a positive light. While the narrative clearly presents his death as a heroic sacrifice to stop the Cybermen, extended media offers alternative interpretations.

Adric (Matthew Waterhouse) in *Doctor Who*

Adric (Matthew Waterhouse) in *Doctor Who*

The 1983 serial Terminus offers another example of potential LGBTQI+ subtext when viewed through a modern lens. The story revolves around Lazar’s disease, a leprosy-like illness, and the societal stigma and fear surrounding it. This aired during the escalating AIDS crisis, with the first confirmed death in December 1981. The parallels between the treatment of Lazar’s disease sufferers and the real-world stigma faced by those with HIV/AIDS are striking.

The Vanir, tasked with managing Lazar’s disease, are themselves dying from addiction to Hydromel, an expensive cure. This could be seen as an analogy for the early, limited, and often inaccessible treatments for AIDS. The societal fear and ostracization of Bor, an elderly Vanir dying from Hydromel addiction, further mirror the real-world prejudice and fear directed at individuals with HIV/AIDS.

Hydromel can also be interpreted as a precursor to PrEP (Pre-exposure prophylaxis), a medication that offers protection against HIV. Like Hydromel, PrEP was not initially readily accessible, becoming widely available in the UK only in 2020, mirroring Hydromel’s initial exclusivity and high cost. Nyssa’s departure in Terminus, to find a way to make Hydromel freely available, can be seen as analogous to the fight for wider and more equitable access to HIV prevention and treatment.

Nyssa (Sarah Sutton) in *Terminus*

Nyssa (Sarah Sutton) in *Terminus*

Also in the 1983 season opener, Arc of Infinity, Tegan’s cousin Colin and his friend Robin’s Amsterdam trip is laden with homoerotic subtext. Robin’s question to Colin about sleeping in his clothes and the overall atmosphere of their opening scene carry strong suggestive undertones. Even their shared hostel room booking adds to the ambiguity, leaving viewers to wonder about the sleeping arrangements.

Prior to the late 1980s, several Doctor Who production members were themselves part of the LGBTQI+ community, including Peter Grimwade and John Nathan-Turner. Grimwade, a director and writer for the show, was openly gay. Nathan-Turner’s sexuality was also publicly known, and he was in a relationship with Doctor Who‘s production manager Gary Downie. Nathan-Turner’s flamboyant style and the show’s increasingly camp aesthetic during his tenure (1980-1989) contributed to its appeal for LGBTQI+ audiences. While some criticize his era, he deserves credit for keeping the show running amidst BBC efforts to cancel it.

Companion Turlough, from the Davison era, is another character open to LGBTQI+ interpretation. While initially conceived as asexual, Turlough exhibits traits that, through a modern lens, can be read as homosexual, albeit often relying on negative stereotypes. His exile to an all-boys school and portrayal as a tempter figure align with some harmful gay stereotypes. However, scenes like the one in Enlightenment, where Turlough is thrown to the ground by Captain Wrack, a dominant female character in leather, and ordered to crawl, are undeniably suggestive and could be interpreted as intentionally coded for a knowing LGBTQI+ audience.

Turlough in *Mawdryn Undead*

Turlough in *Mawdryn Undead*

While John Nathan-Turner’s intent is debated, the prevalence of LGBTQI+ undertones during his era is undeniable. Despite facing homophobic attacks in fan publications, Nathan-Turner was at least complicit in, if not directly responsible for, the coded LGBTQI+ elements present in characters like Turlough. The stereotypical portrayal of Turlough, with his cosmopolitan tastes and catty demeanor, is problematic, but also undeniably recognizable as a coded gay character for viewers at the time. His abusive relationship with the Black Guardian can also be interpreted as a metaphor for unhealthy power dynamics within same-sex relationships, prevalent stereotypes at the time. Turlough’s “enlightenment” in turning away from the Black Guardian could be viewed as rejecting societal corruption or even accepting his true identity.

Towards the late 1980s, The Curse of Fenric featured Doctor Judson and Commander Millington. Writer Ian Briggs later confirmed a past romantic relationship between them, with Judson serving as an allegory for Alan Turing, who was persecuted for his homosexuality. While the overt homosexual element was removed from the televised version, subtle hints of their relationship remain, especially for those aware of the backstory.

Doctor Judson and Commander Millington in *The Curse of Fenric*

Doctor Judson and Commander Millington in *The Curse of Fenric*

Rona Munro, the writer of Survival, intended lesbian undertones in the relationship between Ace and Kara. While the Cheetah People’s costumes and makeup obscured some of the intended nuances, a slow-motion running scene between Ace and Kara retains a romantic subtext, suggesting Ace’s attraction to Kara.

The Happiness Patrol (1988) is perhaps the most overtly LGBTQI+ themed story of the 1980s, directly satirizing Margaret Thatcher’s government and referencing Section 28, which banned the promotion of homosexuality in schools. The story’s camp aesthetic, with a pink TARDIS and brightly dressed Happiness Patrol members, is unmistakable. A scene of silent protest by citizens challenging societal norms can be seen as an inversion of a Pride event. Susan Q’s line, “I’m tired of… smiling and pretending I’m something I’m not,” powerfully echoes the experience of coming out. The entrapment of a man seeking connection with “killjoys” mirrors real-life police tactics used against gay men. Even the villain’s husband running off with another man at the story’s end adds to the overt LGBTQI+ themes.

The Happiness Patrol in *Doctor Who*

The Happiness Patrol in *Doctor Who*

The Wilderness Years and Expanded Media

Following Doctor Who‘s cancellation in 1989, the “Wilderness Years” (1990-2005) saw LGBTQI+ representation flourish in expanded media like books and comics. Novels like Tragedy Day, Human Nature, and Damaged Goods featured gay characters. Damaged Goods, written by future showrunner Russell T Davies, depicted the Doctor’s companion Chris Cwej on a date with a man. Chris’ bisexuality was further explored in later novels.

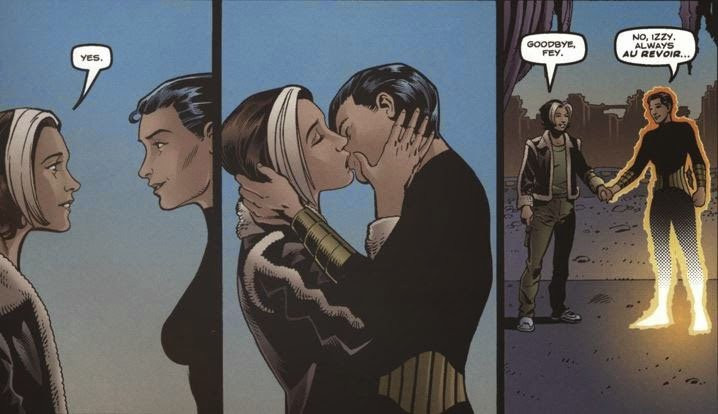

Companion Sam, in the Eighth Doctor novels, was also portrayed as bisexual, with attractions to both men and women. The Eighth Doctor himself was depicted in various relationships, including a romantic relationship with a man named Karl Sadeghi in The Year of the Intelligent Tigers. He also kisses his male companion Fitz in Dominion and flirts with him in The Eater of Wasps. Most famously, in the Oblivion comic, Eighth Doctor companion Izzy kisses another female character, Fey, marking Izzy’s acceptance of her sexuality.

Izzy and Fey in *Doctor Who: Oblivion* comic

Izzy and Fey in *Doctor Who: Oblivion* comic

Even the comedic 1999 Comic Relief skit, The Curse of Fatal Death, offered an early, humorous take on a female Doctor, with the Doctor regenerating into Joanna Lumley. While the skit’s ending, where Emma breaks off her engagement due to the Doctor’s regeneration, is somewhat problematic, it foreshadowed Steven Moffat’s later inclusion of LGBTQI+ themes during his tenure as showrunner.

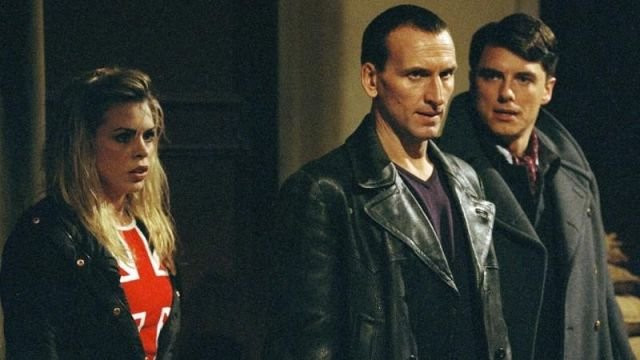

The Revival and Overt Representation

The 2005 Doctor Who revival marked a turning point. The opening episode, Rose, included the first explicit use of the word “gay” in the show, with the Doctor remarking, “That won’t work; he’s gay and she’s an alien,” while flipping through a magazine. Russell T Davies, who had previously created the groundbreaking LGBTQI+ series Queer as Folk, brought a more open and inclusive approach to Doctor Who. The shared surname between Rose Tyler and Vince Tyler from Queer as Folk might even suggest a subtle connection between the two universes. Lady Cassandra’s line about having been a boy in the distant past also introduced transgender themes, albeit briefly and perhaps clumsily.

Rose’s line, “it was so gay,” after the Doctor is slapped, is a moment that hasn’t aged well. However, it reflects the evolving language and understanding of LGBTQI+ issues in 2004, a time when representation was still limited and often stereotypical.

Captain Jack Harkness kisses the Doctor

Captain Jack Harkness kisses the Doctor

Crucially, 2005 also introduced Captain Jack Harkness, Doctor Who‘s first openly gay companion (pansexual is a more accurate descriptor). Jack’s sexuality was presented matter-of-factly, without fanfare. His kiss with the Doctor in The Parting of the Ways, while motivated by circumstance, was the first same-sex kiss in the main Doctor Who series. Jack’s sexuality was further explored in the spin-off Torchwood, where his relationship with Ianto Jones became central.

Russell T Davies’ commitment to LGBTQI+ inclusion significantly expanded the show’s LGBTQI+ fanbase. The 2008 London Pride event even paused for audiences to watch the Journey’s End finale on a large screen in Trafalgar Square, highlighting the show’s cultural impact within the community. Davies’ era introduced numerous characters who were explicitly LGBTQI+, including River Song, Jenny, Vastra, and even Clara Oswald, with a playful suggestion of a past encounter with Jane Austen.

In 2017, Bill Potts, played by Pearl Mackie (who herself later came out as bisexual), became the first explicitly lesbian companion. Bill’s relationship with Heather, a woman who became sentient oil, further normalized LGBTQI+ relationships within the Doctor Who universe. Their reunion in The Doctor Falls, with Heather rescuing Bill after her Cyberman conversion, offered a poignant and hopeful resolution to their love story.

Bill Potts and Heather in *Doctor Who*

Bill Potts and Heather in *Doctor Who*

More recently, Yasmin Khan’s romantic feelings for the Thirteenth Doctor were explored. While fans largely supported the pairing, the Doctor ultimately chose friendship, citing past heartbreak associated with romantic relationships with companions. Yaz’s feelings, though perhaps appearing sudden to some, were foreshadowed throughout Jodie Whittaker’s era, including Yaz’s mother’s earlier question about her relationship with the Doctor.

Spin-offs like Torchwood continued to explore LGBTQI+ themes, featuring Jack and Ianto’s relationship and other same-sex pairings. However, Torchwood also faced criticism for occasionally problematic portrayals, such as Owen’s use of alien pheromones for non-consensual encounters and Jack’s transphobic comment in Greeks Bearing Gifts.

Captain Jack Harkness and Ianto Jones in *Torchwood*

Captain Jack Harkness and Ianto Jones in *Torchwood*

Planned storylines for The Sarah Jane Adventures included Sarah Jane’s son Luke Smith coming out as gay, but the show’s premature end prevented this development. Class, another spin-off, featured a same-sex relationship between characters Charlie and Matteusz.

The casting of Jodie Whittaker as the first female Doctor and Ncuti Gatwa, an openly gay Black man, as the Fifteenth Doctor, further solidifies Doctor Who‘s commitment to diversity and representation. The concept of Time Lords being gender-fluid adds another layer to the show’s exploration of identity.

Doctor Who has undergone a remarkable evolution since 1963. From near-total absence of LGBTQI+ representation in its early years to allegorical explorations of prejudice and coded characters, to overt representation and celebration of diversity in the modern era, Doctor Who has consistently offered something for everyone. Regardless of sexuality, creed, color, or background, Doctor Who embraces inclusivity. The Doctor and companions can be anyone, reflecting the show’s core message of universal acceptance. Doctor Who has become a beacon of diversity on television, and it’s clear why it continues to inspire LGBTQI+ individuals worldwide. Long may this legacy endure!