Celebrating five decades of captivating audiences, Doctor Who, the world’s longest-running science fiction series, has consistently delivered stories that are both entertaining and thought-provoking. As we delve into the show’s rich history, certain episodes stand out, not only for their narrative brilliance but also for their profound exploration of complex themes. “The War Games,” a monumental ten-part serial from 1969, is one such story. This epic adventure, marking a pivotal moment in Doctor Who history, serves as a powerful commentary on the futility and manipulation inherent in war, making it a relevant and resonant piece even today.

Well, what was happening? Why was it so difficult to move?

It was the Time Lords.

But they’re your own people, aren’t they, Doctor?

Yes, that’s right.

Why did you run away from them in the first place?

What? Well, I was bored.

What do you mean, you were bored?

Well, the Time Lords are an immensely civilised race. We can control our own environment, we can live forever, barring accidents, and we have the secret of space time travel.

Well what’s so wrong in all that?

Well we hardly ever use our great powers. We consent simply to observe and to gather knowledge.

And that wasn’t enough for you?

No, of course not. With a whole galaxy to explore? Millions of planets, eons of time, countless civilisations to meet?

Well, why do they object to you doing all that?

Well, it is a fact, Jamie, that I do tend to get involved with things.

– Jamie, the Doctor and Zoe

“The War Games” is more than just a science fiction adventure; it signifies the end of an era for Doctor Who. It was the final full appearance of Jamie McCrimmon as a companion, the swansong for Patrick Troughton’s beloved Second Doctor, and the last Doctor Who serial produced in black and white. The transition that followed, ushering in Jon Pertwee’s Third Doctor, was transformative. The series leaped into color, shifted its setting to Earth, and adopted a new format, creating a seismic shift for viewers in 1969, just six years into the show’s run.

While “The War Games” is undeniably lengthy, clocking in at ten episodes, it’s far from tedious. Instead, it stands as a compelling and fitting farewell to the Second Doctor’s era, particularly his “cosmic hobo” persona. Viewed through a modern lens, the forced regeneration at the story’s climax carries a heavier weight, resonating with the emotional depth of later regeneration scenes, like the Tenth Doctor’s poignant pleas for more time. “The War Games” is not just a goodbye to a specific Doctor but also a poignant farewell to a particular style and tone that defined Doctor Who in its early years.

Run!

Run!

The Doctor, played by Patrick Troughton, and his companions Jamie and Zoe, running from danger in Doctor Who The War Games, highlighting the classic era of Doctor Who.

The serial’s length, often cited as its main flaw, is indeed considerable. “The War Games” holds the record for the longest surviving Doctor Who story, surpassed only by the partially missing “The Daleks’ Master Plan.” In a show often criticized for padding even four-part stories, a ten-episode serial might seem daunting. The classic series, particularly, had a tendency to rely on repetitive plot structures – “investigate-capture-escape-recapture” – to stretch narratives, and “The War Games” is not entirely immune to this. The Doctor and his companions find themselves repeatedly escaping and being recaptured, mirroring the experiences of the villains as well.

All fired up…

All fired up…

Soldiers in a tense standoff during Doctor Who The War Games, demonstrating the war-torn setting and human conflict focus of the episode.

The character of Von Weich, a henchman, exemplifies this padding. Captured by the resistance and ineptly guarded by Private Moor (played by Patrick Troughton’s son), Von Weich’s escape, facilitated by Moor’s foolishness in returning his mind-control monocle, feels like a subplot designed purely to extend the runtime. Von Weich’s swift recapture and demise further underscore this sense of narrative stretching.

Even the final episode, pivotal for its introduction of the Time Lords and the Doctor’s regeneration, includes a somewhat unnecessary escape attempt by the War Lord. Despite being captured and judged by the Time Lords, his men orchestrate a brief escape, involving the kidnapping of the Doctor and a TARDIS hijacking attempt. This, too, is quickly resolved with his recapture and sentence of non-existence. While these moments aim to build suspense, their frequency dilutes their effectiveness, highlighting the serial’s padded nature.

I have a Hun-ch he

I have a Hun-ch he

A stern-looking villain from Doctor Who The War Games, embodying the human antagonists and political intrigue within the storyline.

Terrance Dicks, one of the writers of “The War Games,” acknowledged these issues, stating that the extended length was partly due to script project collapses and chaotic production circumstances. He conceded that the story could have been more impactful if condensed, potentially losing about four episodes. However, Dicks also praised the core concept of different war zones and time periods being manipulated, and the effectiveness of some cliffhangers.

Despite its pacing issues, “The War Games” possesses undeniable strengths. Within its ten episodes lies a compelling six-part story yearning to break free. The serial’s length, paradoxically, allows for certain narrative advantages that contribute significantly to its impact.

The Doctor and Jamie in disguise in Doctor Who The War Games, showcasing the espionage and infiltration aspects of the plot.

One such advantage is the masterful slow-burn mystery established in the initial episodes. The drawn-out plot, while sometimes repetitive, allows for a gradual unveiling of the sinister scheme. The enigmatic Mr. Smythe and his mind-control glasses, coupled with the amnesiac soldiers, create an atmosphere of intrigue. The arrival of Roman soldiers further deepens the mystery, and the narrative skillfully unravels layer by layer.

The extended format also builds a sense of immense scale. “The War Games” presents a problem so colossal that it necessitates the Doctor summoning the Time Lords, a momentous decision in itself. This isn’t a localized threat; it’s a galaxy-spanning conspiracy. The story meticulously reveals the hierarchy of villains, starting with minor figures like Smythe and Von Weisch, then progressing to the Security Chief and the War Chief, culminating in the War Lord, who remains a shadowy presence until well into the serial.

Fog of war…

Fog of war…

Soldiers in a foggy war zone in Doctor Who The War Games, emphasizing the episode’s depiction of varied historical war settings.

Even after the War Lord’s introduction, his detached demeanor adds to his menace. The focus shifts to the power struggles between the Security Chief and the War Chief, creating the impression of the War Lord as a more sinister, remote force orchestrating the mass conflict. This narrative technique effectively conveys the vastness of the plot and the gravity of the situation. While characters like Smythe and Von Weisch might feel like placeholders, they serve the crucial purpose of illustrating the infrastructure of this large-scale operation, enhancing the audience’s understanding of the unfolding events.

Just in case you forgot this was made during the sixties…

Just in case you forgot this was made during the sixties…

Sixties style technology in Doctor Who The War Games, reminding viewers of the era of production and the show’s visual aesthetic.

The length also allows for clever narrative framing devices. The opening and closing episodes utilize courtroom scenes, creating a bookend effect that suggests a tighter production structure than behind-the-scenes accounts might imply. The initial trial allows the Doctor to voice his sense of injustice, albeit in a less direct way than he would with the Time Lords. “This is a travesty of justice,” he declares, a sentiment that echoes his feelings during the Time Lord trial at the story’s conclusion. His frustration with the court’s refusal to consider evidence mirrors his later exasperation with the Time Lords’ unyielding judgment. “Well, if you’re not going to allow them to answer, what is the use?” he asks Smythe, trapped in a Kafkaesque situation. The final trial, while presenting an illusion of due process, is ultimately a swift path to sentencing. Despite the promise of choosing his new face, the Time Lords’ impatience leads to an imposed regeneration.

Across the board…

Across the board…

The War Lord and Security Chief strategizing in Doctor Who The War Games, showing the layered villain structure of the plot.

Crucially, this was only the second regeneration in Doctor Who history. The rules weren’t firmly established, and the concept wasn’t yet directly equated with death. Given the later emotional weight associated with regeneration, the Time Lords’ sentence now seems far more severe. They are not just changing his appearance; they are, in effect, ending the Second Doctor’s existence. This adds a layer of bleakness to “The War Games” that is even more pronounced today.

Another benefit of the extended length is the opportunity for Patrick Troughton to deliver a nuanced and prolonged emotional arc for the Second Doctor. The story begins relatively lightheartedly, with the Doctor and his companions even sharing moments of levity. However, a sense of unease gradually permeates the Doctor’s demeanor. A rare affectionate gesture – a kiss on Zoe’s forehead – hints at a deeper emotional undercurrent.

Talk about doing things by the book…

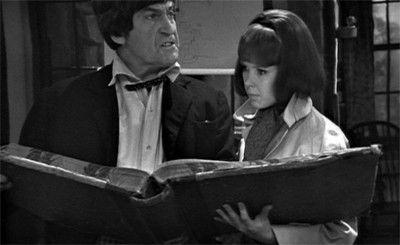

Talk about doing things by the book…

The Doctor examining documents in Doctor Who The War Games, highlighting his investigative approach and intellectual prowess.

Throughout the serial, Troughton masterfully portrays the Doctor’s growing anxiety and concern. He recognizes familiar Time Lord technology in the War Lord’s devices. “Yes, it’s only a question of overriding the master control,” he says while hijacking a SIDRAT, adding, “Now, it’s a slightly different design to the TARDIS.” The subtle but significant “slightly” underscores his growing suspicion. When the War Chief’s forces attack, the Doctor’s assurance to Jamie, “Don’t worry. These things are impregnable against outside attack,” followed by Jamie’s astute question, “You mean like the TARDIS?” and the Doctor’s telling silence, all contribute to a palpable sense of unease.

In the latter half of the serial, as the scope of the threat becomes clear, the Doctor’s composure visibly crumbles. He even resorts to a feigned surrender, waving a handkerchief in a moment of apparent desperation. “What are you going to do with us?” he demands, “I won’t have my friends ill-treated, you know.” His insistent “I am here under a flag of truce. I demand to know what you are going to do with us,” reveals genuine desperation beneath the surface ruse.

Where

Where

The Doctor looking concerned in Doctor Who The War Games, showing Patrick Troughton’s portrayal of the Doctor’s growing worry and determination.

Even his characteristic patience seems to fray. When Russell expresses impatience with the slow pace of deprogramming hypnotized soldiers, “If you’re going to do them all one by one, it’ll take until doomsday,” the Doctor snaps back, “Look, Mister Russell, I am doing my best!” This outburst contrasts with the Second Doctor’s usual carefully controlled demeanor, suggesting the immense pressure he is under. While episodes like “Tomb of the Cybermen” showcased the Second Doctor’s underlying control, “The War Games” reveals that control slipping, adding depth to his portrayal.

The extended length also enriches the social fabric of the war-torn world depicted in the serial. We gain a sense of the vastness of the operation and its inherent decay. Watching “The War Games,” one wonders if the scheme would have ultimately collapsed even without the Doctor’s intervention, given the growing resistance. While some of this world-building might be attributed to padding, it nonetheless fleshes out the setting, making it more believable and immersive.

The Doctor in disguise as an advisor in Doctor Who The War Games, demonstrating his cunning and ability to blend into different situations.

However, the portrayal of the international resistance fighters is marred by crude ethnic stereotypes. The Russian character’s pronouncements and the hot-tempered Mexican’s caricature are particularly jarring and politically insensitive by modern standards. The Mexican character’s aggressive stupidity even undermines the Doctor’s plan, highlighting the problematic nature of these portrayals.

Despite these shortcomings, the serial does offer a sense of organizational depth. The Security Chief’s paranoia regarding the War Chief, initially seeming excessive, proves ultimately justified. His suspicious reaction to the Doctor’s arrival and his misinterpretations are logical within the context of the plot, adding a layer of intrigue even if it sometimes feels like a way to fill time.

The game is afoot…

The game is afoot…

The War Lord and Security Chief in a command center in Doctor Who The War Games, illustrating the strategic and command aspects of the war games scenario.

“The War Games” also boasts striking visuals. The scene where Smythe and Von Weisch play Risk with real human lives is particularly memorable, underscoring the callous manipulation at the heart of the conflict.

If my troops make a push here, what resistance can you put up?

Along here we shall have pillboxes, machine gun nests, landmines. You’ll have no chance, but it will be an excellent test of the morale of your humans. Your entire force will be wiped out.

Ah, but I will use my reinforcements to turn your flank… there!

Then it will not be a fair battle.

Perhaps not, but it will be an excellent test of your morale.

Similarly, the SIDRATs transporting soldiers like toys effectively conveys the scale and dehumanization of the war games.

… and the legion shall be few…

… and the legion shall be few…

Roman soldiers marching in Doctor Who The War Games, showcasing the historical armies caught up in the alien war games.

The black and white cinematography, arguably enhancing the classic Doctor Who aesthetic, works exceptionally well in “The War Games.” While special effects might appear less sophisticated in black and white, the production design shines. Despite the limitations of depicting a Roman legion with only a handful of actors, the stylized headquarters, trench scenes, and military base sets are visually impressive. The retro-chic spiral design in the mind-control room is a particularly noteworthy detail.

Remarkably, for a serial of its length, “The War Games” largely eschews traditional Doctor Who monsters. While the Yeti, Cybermen, Daleks, Ice Warriors, and Quarks briefly appear in the final episode, the primary antagonists are human, or human-like. This focus on human evil sets “The War Games” apart and contributes to its mature tone. As noted in “The Television Companion,” contemporary audience research indicated that some viewers, particularly adults, appreciated the absence of “inhuman creatures,” finding the story “all the better for it.”

Not quite Civil War…

Not quite Civil War…

Soldiers from different historical periods clashing in Doctor Who The War Games, illustrating the chaotic and manipulated nature of the conflicts.

The greatest threat in “The War Games” is not a fantastical monster but the mundane and calculated evil of dictators and warmongers. This shift in focus suggests a more mature and nuanced form of storytelling. Perhaps the Second Doctor, known for battling otherworldly threats, is somewhat out of his element confronting such grounded human cruelty. This experience might even inform the Third Doctor’s later cynicism towards humanity.

Lord of War…

Lord of War…

The War Lord, the mastermind villain of Doctor Who The War Games, representing the intellectual and strategic threat.

“The War Games” is also iconic for introducing the Time Lords to Doctor Who mythology. After six seasons, the series finally delves into the Doctor’s origins and his people. This deliberate pacing mirrors Russell T. Davies’ approach in the revived series, delaying extensive backstory exposition. The Time Lords’ arrival is a momentous event, raising the question of why the Doctor hadn’t sought their help before. Jamie voices this audience query directly: “Well,” he asks, “why haven’t you asked them for help before?” The Doctor replies, “I’ve never really needed it before, Jamie.”

Man, I've had nights like that…

Man, I've had nights like that…

The Doctor in chains during his trial by the Time Lords in Doctor Who The War Games, marking a pivotal moment in Doctor Who lore and the introduction of the Time Lords.

However, “The War Games” establishes that Time Lord intervention comes at a steep price. The War Chief warns of dire consequences if the Doctor summons them: “You can’t, unless… Doctor, you mustn’t call them in or it will be the end of us. They’ll show no mercy.” His words prove prophetic, as the Doctor’s decision leads directly to his trial, forced regeneration, and exile to Earth.

“The War Games” fittingly concludes the Second Doctor’s anarchic era. The Eleventh Doctor’s self-description in “The Pandorica Opens” – a man who would “just drop out of the sky and tear down your world” – perfectly encapsulates Troughton’s Doctor. “The War Games” sees him undertaking his most ambitious “tear down” project yet, but at a personal cost. To end the immense suffering caused by the War Games, he must sacrifice himself and his freedom.

It

It

Time Lords judging the Doctor in Doctor Who The War Games, depicting the introduction of Time Lord society and their imposing presence.

The cycle of death and rebirth inherent in regeneration makes “The War Games” a fitting farewell to this Doctor. The Second Doctor confronts an evil he cannot defeat alone and must accept the consequences of seeking help. This sets the stage for the Third Doctor, a more establishment-aligned figure. Paul Cornell famously quipped that “they exiled the Doctor to Earth and made him a Tory.” While perhaps unfair, the Third Doctor is undeniably less prone to systemic disruption than his predecessor, making “The War Games” a powerful climax before this shift.

While Time Lord culture would be further developed by Robert Holmes in “The Deadly Assassin,” “The War Games” already hints at their stagnation. Even if the full extent of Time Lord corruption isn’t yet revealed, the serial suggests a society that has become complacent and detached.

In a bit of a fix…

In a bit of a fix…

Jamie and Zoe in captivity during Doctor Who The War Games, highlighting the companion’s roles and the dangers they face.

The Time Lords in “The War Games” are not heroic saviors. They resort to torture to extract confessions. The Doctor expresses impatience and sarcasm towards them. “No, no, of course, you’re above criticism, aren’t you,” he mutters. He sarcastically praises their “efficient” method of wiping Zoe and Jamie’s memories, barely concealing his contempt for their casual disregard for individual autonomy.

The Time Lords’ punishment of the Doctor, while perhaps not initially perceived as harshly as it is today, is unambiguously damaging to the humans caught in their web. Earlier in “The War Games,” Jamie’s compassion for a captured redcoat highlights his character development. However, upon returning to Earth, his immediate instinct is to attack an enemy soldier, demonstrating the erasure of his personal growth by the Time Lords’ memory manipulation. The Doctor’s smile at this moment feels forced and sarcastic, masking his true feelings about the Time Lords’ actions.

A short fuse…

A short fuse…

The Doctor displaying frustration in Doctor Who The War Games, showcasing the emotional strain and urgency of the situation.

“The War Games” foreshadows many themes and plot elements later explored by Russell T. Davies in his revival of Doctor Who. Davies’ series finales often featured the Doctor confronting the Time Lords again. His gradual reveal of the Doctor’s backstory echoes the approach taken in classic Doctor Who. Specific plot devices in “The War Games” also anticipate Davies’ era.

Oh, what a lovely war…

Oh, what a lovely war…

Soldiers in trenches during Doctor Who The War Games, depicting the historical war settings and the grim reality of conflict.

The War Chief’s technology, for example, includes what Davies would later term a “perception filter.” Throughout “The War Games,” advanced technology and altered realities are presented in ways that human characters struggle to perceive. Smythe’s hidden communication device and the brainwashed soldier’s inability to comprehend his alien surroundings prefigure this concept. The scientist’s boast, “Objects which are beyond his comprehension, he will not see at all,” strongly resonates with Davies’ later use of perception filters.

Keep your head…

Keep your head…

A soldier with a head injury in Doctor Who The War Games, highlighting the human cost and suffering of war depicted in the story.

The dialogues between the Doctor and the War Chief also prefigure the Doctor-Master dynamic in Davies’ era, particularly in “The Sound of Drums” and “The Last of the Timelords.” Like the Master, the War Chief, a renegade Time Lord, offers a dark mirror to the Doctor. Both use humanity as pawns in their schemes, but for different reasons. While the Master seeks to torment the Doctor, the War Chief recognizes humanity’s potential for savagery.

The war games on this planet are simply the means to an end. The aliens intend to conquer the entire galaxy. A thousand inhabited worlds.

Yes, but why choose the people of the Earth?

They are the most suitable recruits for our armies. Man is the most vicious species of all.

Well, that simply isn’t true.

Consider their history. For a half a million years they have been systematically killing each other. Now we can turn this savagery to some purpose.

– the Doctor and the War Chief

The War Chief embodies a rejection of the Time Lord philosophy of non-interference, contrasting sharply with the Doctor’s more interventionist but ultimately benevolent approach. The Doctor’s contempt for the War Chief is palpable: “You have given these aliens our science and our knowledge to carry out this disgusting plan.”

Branching out…

Branching out…

The War Chief using advanced technology in Doctor Who The War Games, showcasing the Time Lord technology misused for war and manipulation.

Ultimately, the Doctor and the War Chief diverge in their sense of responsibility. When their plans unravel, the War Chief attempts to escape, abandoning the displaced soldiers. The Doctor, in contrast, refuses to abandon those in need. “We could just go to the landing bay,” the War Chief suggests. “order a machine and leave.” The Doctor’s simple reply, “You could, we can’t,” encapsulates his core moral difference.

“The War Games,” as Patrick Troughton’s final story, is filled with memorable Second Doctor moments. His bluffing his way into a military prison as an indignant official is a classic Troughton scene: “Don’t you address me like that, sir!” he demands. “This is disgraceful! I shall make a complaint directly to the Minister himself!”

The first trial of the Timelord…

The first trial of the Timelord…

The Doctor standing trial before the Time Lords in Doctor Who The War Games, a landmark scene introducing Time Lord justice and the Doctor’s defiance.

Another highlight is the scene where he hijacks a student lecture, cleverly manipulating the teacher into revealing crucial information needed to reverse the brainwashing. Troughton’s charisma and disarming charm shine in this distinctly Doctor Who moment.

While “The War Games” may be too long and uneven to be considered a perfect Doctor Who story, its ambition, thematic depth, and historical significance are undeniable. It offers fascinating ideas, utilizes its length to build scale and character development, and serves as a powerful farewell to an era. Despite its flaws, “The War Games” remains a captivating and more entertaining serial than its runtime might suggest, cementing its place as a timeless classic in Doctor Who history, particularly for its exploration of the themes of “Doctor Who The War”.