The saying “an apple in a day keeps the doctor away” is deeply ingrained in popular culture, suggesting that simply eating an apple daily can maintain good health and reduce the need for doctor visits. But is there any scientific basis to this age-old adage? While the idea of preventative health through diet is appealing, it’s important to examine the evidence behind such claims. This article delves into a comprehensive study that investigated the link between daily apple consumption and healthcare utilization, providing a nuanced perspective on this widely accepted health advice.

The Historical Roots of “An Apple a Day”

The proverb we know today, “An apple a day keeps the doctor away,” has a fascinating history. Its origins trace back to Wales in 1866, though in a slightly different, rhyming form: “Eat an apple on going to bed, and you’ll keep the doctor from earning his bread.” By 1913, it appeared in its current, more concise version, embedding itself into the common wisdom about health and diet. Historically, the saying emerged during a time when medical practices were less advanced, and individuals understandably sought ways to avoid illness and the healthcare of the era. Over time, the apple became a symbol of health and healthy habits, frequently used by public health campaigns and organizations to represent lifestyle choices that promote well-being.

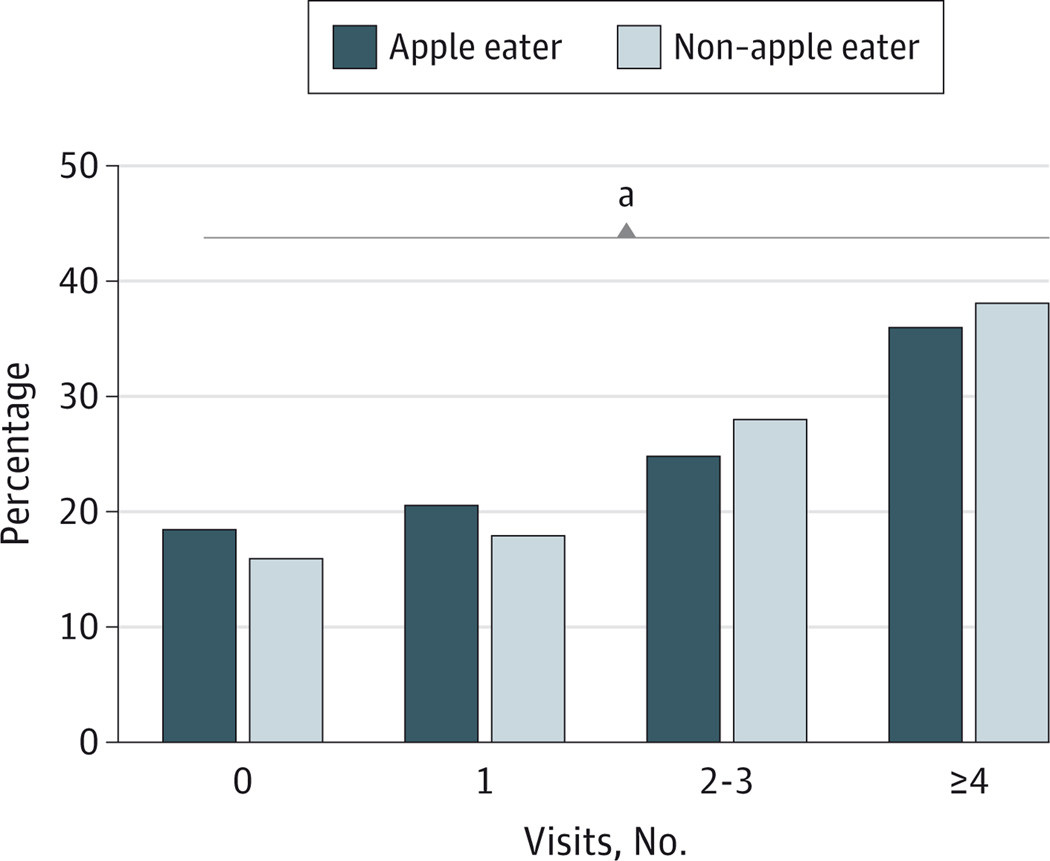

Figure 1

Figure 1

Alt text: Bar chart comparing the distribution of physician visits in the past year between apple eaters and non-apple eaters, illustrating a slight difference in favor of apple eaters.

Apples: A Nutritional Powerhouse?

The perceived health benefits of apples are often attributed to their rich composition of fiber, essential vitamins, minerals, and flavonoids, particularly quercetin. These components have been suggested to play a role in preventing various health issues, including cancer and cardiovascular diseases. Research has explored the potential positive effects of apple consumption on areas ranging from weight management and neurological health to cancer prevention, asthma symptom reduction, and improved heart health. Given these purported benefits, the question naturally arises: does eating an apple daily translate to fewer visits to the doctor?

Investigating the “Apple a Day” Claim: A Detailed Study

To rigorously examine the link between daily apple consumption and healthcare utilization, a study utilized data from the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES). This nationally representative survey provided a robust dataset to analyze the habits and health outcomes of US adults. Researchers compared “apple eaters” (those consuming at least one small apple daily) with “non-apple eaters” to determine if there were significant differences in their use of healthcare services.

The study defined “apple eaters” as individuals who consumed at least 149 grams of raw apple per day, equivalent to a small apple. Healthcare utilization was measured by self-reported data, focusing on:

- Physician Visits: Whether participants had more than one visit to a physician in the past year.

- Hospital Stays: Whether participants had any overnight hospital stays.

- Mental Health Visits: Whether participants visited a mental health professional.

- Prescription Medications: Whether participants used prescription medications in the past month.

Researchers carefully adjusted for various sociodemographic and health-related factors to isolate the potential impact of apple consumption.

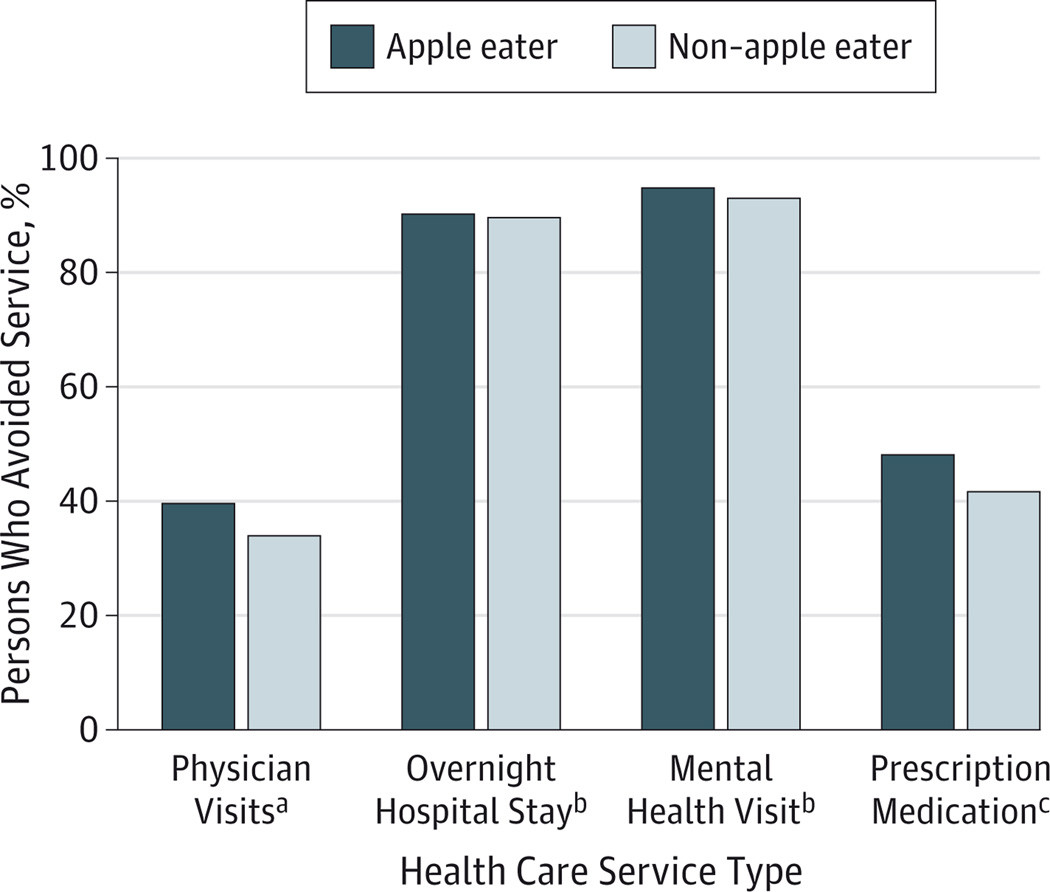

Figure 2

Figure 2

Alt text: Percentage comparison bar graph showing the proportion of apple eaters and non-apple eaters who avoided specific healthcare services, highlighting differences in physician visits and prescription medication use.

What Did the Study Find? Unpacking the Results

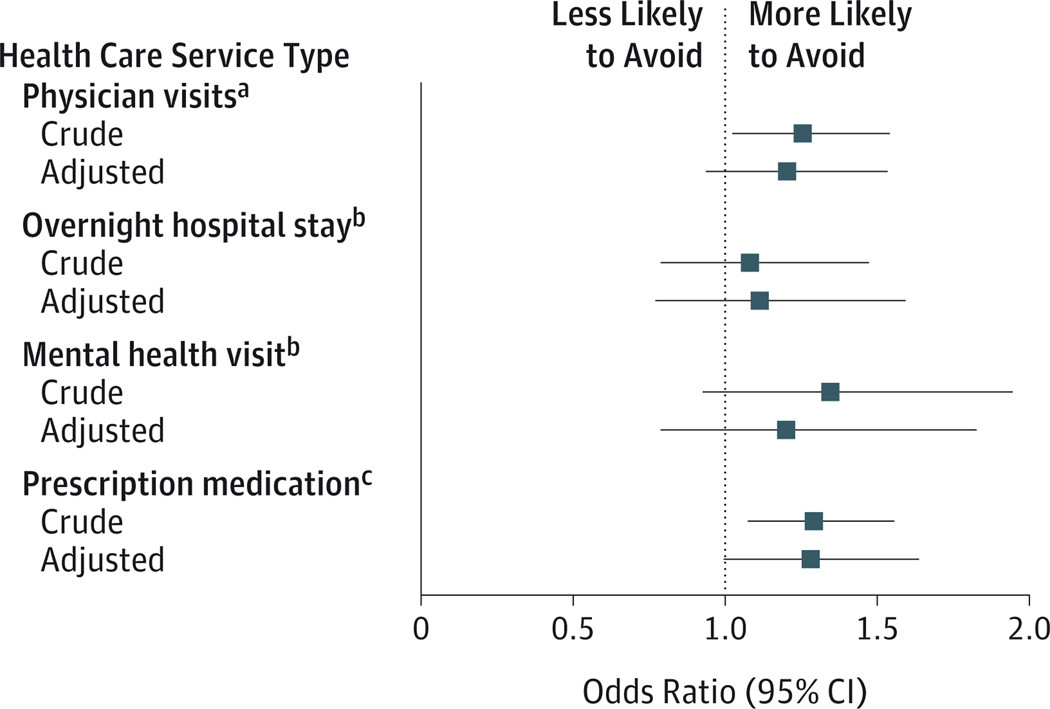

The study identified that approximately 9% of US adults are daily apple eaters. Interestingly, in initial, unadjusted analysis, apple eaters were slightly more likely to have avoided doctor visits and prescription medications compared to non-apple eaters. However, after adjusting for factors like socioeconomic status, lifestyle choices, and health conditions, the association between eating an apple a day and avoiding physician visits became statistically insignificant. This means the initial observed difference could be explained by other factors rather than solely apple consumption.

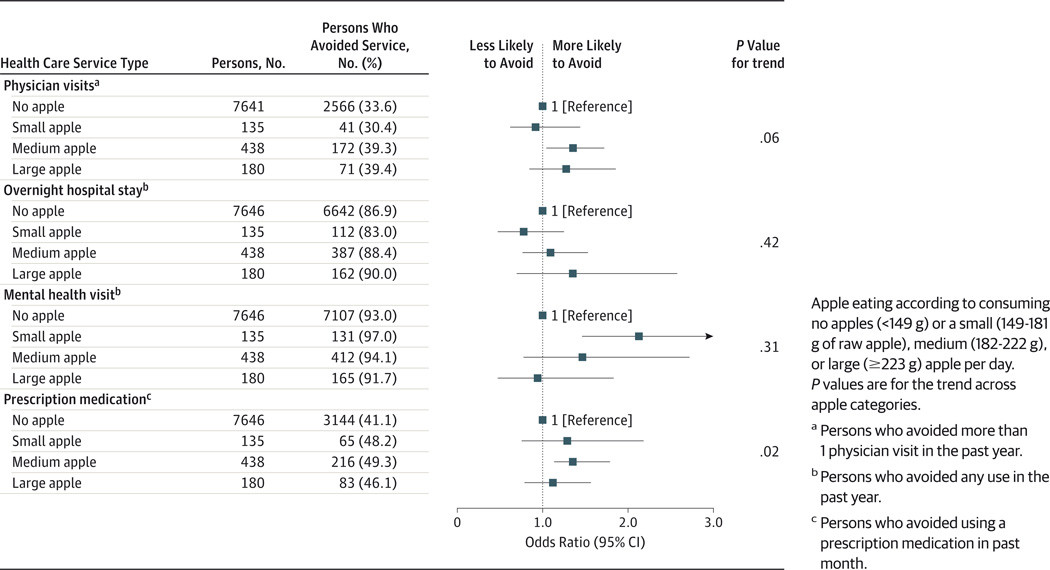

Despite this, a notable finding persisted: even after adjustment, apple eaters showed a marginally significant tendency to use fewer prescription medications. There were no significant differences observed in hospital stays or mental health visits between the two groups. Further analysis exploring different “doses” of apple consumption (small, medium, large) did not reveal a clear dose-response relationship with healthcare avoidance, except again for prescription medication use, where some trend was suggested.

Figure 3

Figure 3

Alt text: Graph displaying crude and adjusted odds ratios for the correlation between daily apple consumption and avoidance of healthcare services, indicating the attenuation of the association after adjustments for confounding variables.

“An Apple a Day Keeps the Pharmacist Away?”

The study’s conclusion suggests that while “an apple a day” may not definitively “keep the doctor away” in terms of overall physician visits, there’s a subtle but potentially meaningful link to reduced prescription medication use. This is a significant point, as prescription costs constitute a substantial portion of healthcare spending. If daily apple consumption causally contributes to lower medication use, promoting apple intake could have implications for managing healthcare costs, particularly related to pharmaceuticals.

The researchers estimated potential cost savings if the entire US adult population consumed an apple a day, focusing solely on prescription medication expenses. While the estimated savings were considerable on paper, it’s crucial to acknowledge the limitations of such calculations and the study itself.

Study Limitations and Future Directions

It’s essential to consider the limitations of this study. Firstly, its cross-sectional design cannot establish a cause-and-effect relationship. While it’s unlikely that reduced medication use leads to apple consumption (reverse causality), other unmeasured factors could be at play. For instance, individuals who eat apples may be generally more health-conscious and engage in other healthy behaviors that contribute to lower medication use. This is known as residual confounding.

Secondly, the reliance on self-reported dietary data and healthcare utilization introduces potential for inaccuracies. However, the 24-hour dietary recall method used in NHANES is considered reasonably reliable for assessing fruit and vegetable intake.

Future research could explore these associations further using prospective studies or experimental designs to establish stronger causal links. “Natural experiments,” such as examining health outcomes following apple crop variations, or controlled interventions, could provide more definitive answers.

Figure 4

Figure 4

Alt text: Chart illustrating crude odds ratios for the association between varying daily apple consumption levels and avoidance of healthcare services, showing no clear dose-response relationship except for prescription medication avoidance.

Conclusion: Re-evaluating the Apple Proverb

In conclusion, while the study doesn’t fully validate the traditional saying “an apple a day keeps the doctor away,” it offers an intriguing update: “an apple a day may keep the pharmacist away.” The evidence suggests that daily apple consumption might be associated with a reduced need for prescription medications, although more research is needed to confirm this relationship and understand the underlying mechanisms.

The study underscores the complexity of health and the multifaceted benefits of fruits like apples. While not a singular solution to avoiding all doctor visits, incorporating apples into a balanced diet is undoubtedly a healthy choice, potentially contributing to reduced reliance on prescription drugs and promoting overall well-being. As research continues to unravel the intricate connections between diet and health, revisiting and refining long-held proverbs with scientific insights proves to be a valuable endeavor.

References

- [#R1]

- [#R2]

- [#R3]

- [#R4]

- [#R5]

- [#R6]

- [#R7]

- [#R8]

- [#R9]

- [#R10]

- [#R11]

- [#R12]

- [#R13]

- [#R14]

- [#R15]

- [#R16]

- [#R17]

- [#R18]

- [#R19]

- [#R20]

- [#R21]

- [#R22]

- [#R23]

- [#R24]

- [#R25]

- [#R26]

- [#R27]

- [#R28]

- [#R29]

- [#R30]

- [#R31]

- [#R32]

- [#R33]

- [#R34]

- [#R35]

- [#R36]

- [#R37]

- [#R38]

- [#R39]

- [#R40]

- [#R41]

- [#R42]

- [#R43]

Supplementary Material

supplement

NIHMS670757-supplement-supplement.pdf (36.9KB, pdf)