David Livingstone.

Doctor David Livingstone (born March 19, 1813, Blantyre, Lanarkshire, Scotland—died May 1, 1873, Chitambo, present-day Zambia) was a transformative figure in the 19th century. A Scottish missionary, qualified doctor, pioneering explorer, and ardent abolitionist, Livingstone profoundly shaped Western perceptions of Africa. His extensive expeditions across the continent not only unveiled its geographical mysteries but also championed the cause of Christianity, legitimate commerce, and the end of the slave trade.

Early Life and Influences

Shuttle Row, David Livingstone’s humble birthplace in Blantyre, Scotland.

Livingstone’s upbringing in Scotland instilled in him the core values that would define his life’s work. Born into a poor yet deeply religious family, he experienced firsthand the values of personal piety, the necessity of hard work, and a relentless pursuit of education. His family’s Scottish Presbyterian background, combined with their Covenanter heritage, fostered a strong sense of mission and unwavering conviction. Living with his parents and six siblings in a single room in a tenement building near a cotton factory on the River Clyde, young David began working in the cotton mill at the age of ten. Despite long working hours, he was determined to learn, using his first week’s wages to buy a Latin grammar book. Initially raised in the Calvinist tradition of the Church of Scotland, Livingstone, following his father’s example, joined a more austere independent Christian congregation as an adult. These formative years forged his resilient character and prepared him for the arduous challenges of his future endeavors in Africa.

Inspired by a call from British and American churches for medical missionaries to serve in China, Livingstone embarked on a path to become a doctor. While continuing to work part-time at the mill, he dedicated himself to studying Greek, theology, and medicine in Glasgow for two years. In 1838, his application to the London Missionary Society was accepted. Although his initial aspiration to go to China was thwarted by the First Opium War (1839–42), a pivotal meeting with Robert Moffat, a renowned Scottish missionary in Southern Africa, redirected his focus to the African continent. Ordained as a missionary on November 20, 1840, Livingstone set sail for South Africa, arriving in Cape Town on March 14, 1841, ready to begin his missionary and exploratory work.

Venturing into the African Interior

Doctor Livingstone’s exploration routes across Africa.

For the subsequent fifteen years, Doctor Livingstone immersed himself in the uncharted territories of the African interior. His motivations were multifaceted: a deep-seated missionary zeal to spread Christianity, an insatiable curiosity for geographical discovery, and a growing abhorrence for the injustices he witnessed, particularly the treatment of Africans by the Boers and Portuguese. He became a vocal critic of slavery and built a reputation as a courageous explorer, devoted Christian, and passionate advocate against the slave trade. However, his intense dedication to Africa sometimes overshadowed his familial responsibilities.

Arriving at Robert Moffat’s mission in Kuruman in July 1841, Livingstone quickly moved northward, seeking to evangelize in regions believed to have larger populations. He believed in empowering “native agents” to spread the Gospel. By 1842, he had ventured further north into the challenging Kalahari Desert than any European before him, gaining valuable knowledge of local languages and cultures. In 1844, an incident during an attempt to establish a mission station at Mabotsa tested his resilience. He was attacked and mauled by a lion, resulting in a severe injury to his left arm. This injury, compounded by a later accident, permanently impaired his ability to aim a rifle in the conventional way, forcing him to shoot from his left shoulder and aim with his left eye.

Doctor Livingstone’s expedition reaches Lake Ngami.

On January 2, 1845, Livingstone married Mary Moffat, Robert Moffat’s daughter. Mary accompanied him on numerous expeditions until concerns for her health and the children’s education necessitated her return to Britain with their four children in 1852. Prior to this separation, Livingstone had already achieved recognition for his surveying and scientific contributions to an expedition that resulted in the first European sighting of Lake Ngami on August 1, 1849. This discovery earned him a gold medal and a monetary award from the Royal Geographical Society in London, marking the start of a long and fruitful relationship with the society, which would become a key supporter of his explorations and ambitions.

Opening a Path to the Interior of Africa

Victoria Falls, a majestic natural wonder discovered by Doctor Livingstone.

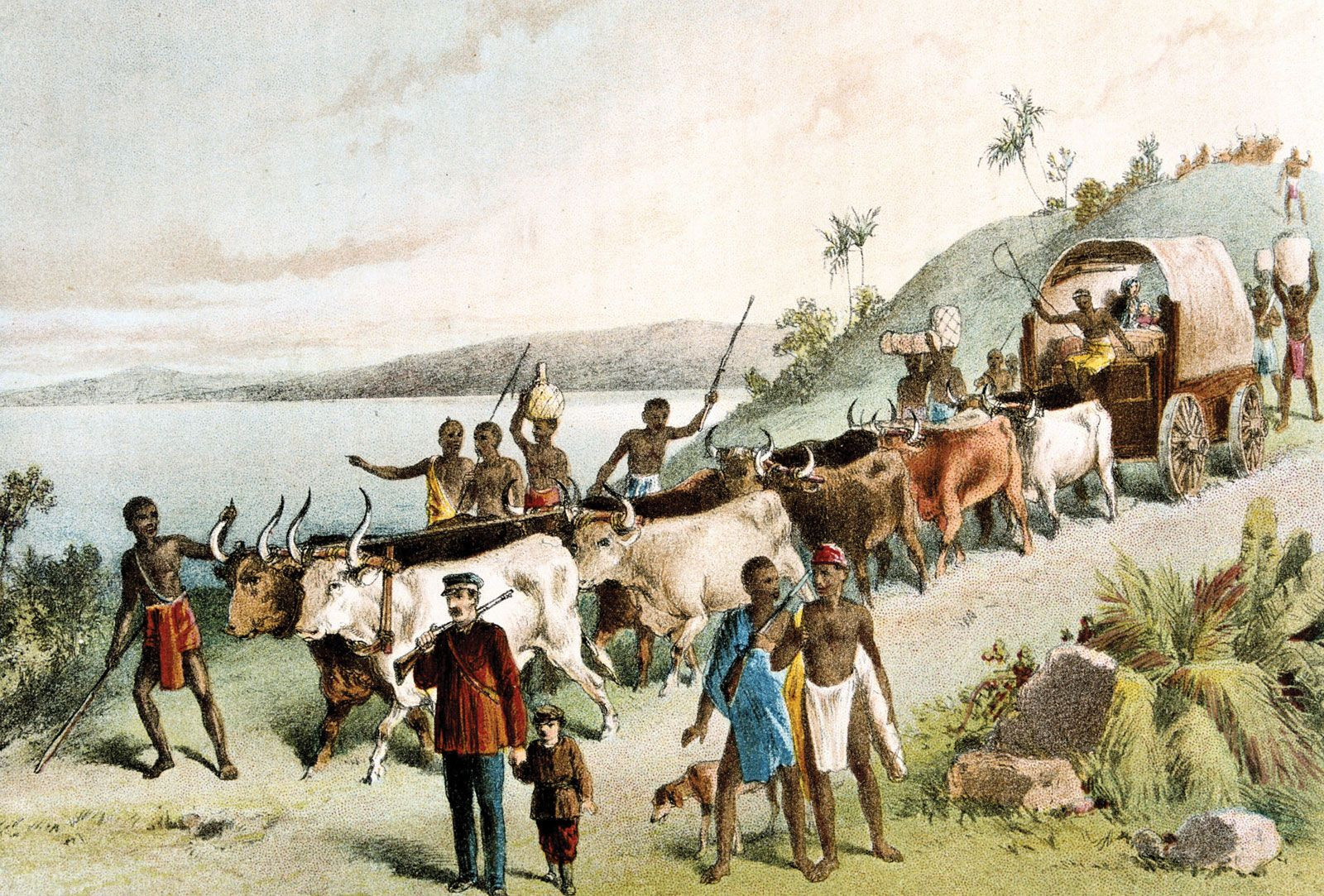

With his family settled in Scotland, Doctor Livingstone was poised to advance his vision of bringing Christianity, commerce, and civilization – a trinity he believed crucial for Africa’s progress – deeper into the continent. In 1853, he famously declared, “I shall open up a path into the interior, or perish.” On November 11, 1853, setting out from Linyanti near the Zambezi River, accompanied by a small group of Africans, Livingstone embarked on a journey northwest. His objective was to find a route to the Atlantic coast that would facilitate legitimate trade, thereby undermining the abhorrent slave trade, and provide a more accessible path to the Makololo people, whom he saw as promising candidates for missionary work. This was also motivated by the destruction of his home in Kolobeng and attacks on his African associates by the Boers in 1852.

After an incredibly challenging journey that tested his physical limits, Livingstone reached Luanda on the west coast on May 31, 1854. Determined to return his Makololo companions home and further explore the Zambezi region, he commenced the return journey on September 20, 1854, as soon as his health allowed. He arrived back in Linyanti nearly a year later, on September 11, 1855. Continuing eastward on November 3, Livingstone explored the Zambezi River region, reaching Quelimane in Mozambique on May 20, 1856. The most iconic moment of this epic journey was his arrival at the Zambezi’s spectacular waterfalls on November 16, 1855. In a display of patriotism, he named them Victoria Falls, in honor of Queen Victoria. Doctor Livingstone returned to England on December 9, 1856, a celebrated national hero. News of his exploits in Africa had captivated the British public and beyond, generating immense interest and admiration.

Doctor David Livingstone, a legendary figure in African exploration.

Livingstone documented his remarkable journey in Missionary Travels and Researches in South Africa (1857). The book became an instant bestseller, selling over 70,000 copies and solidifying his place in history as a significant explorer and missionary writer. Honors were bestowed upon him, and his improved financial situation allowed him to support his family and become independent from the London Missionary Society. Following the publication of his book, Livingstone spent six months touring the British Isles, giving speeches and inspiring audiences. In his address at Senate House, Cambridge University, on December 4, 1857, he expressed his premonition that he might not finish his work in Africa and called upon young university men to continue the mission he had begun. His Cambridge lectures, published as Dr. Livingstone’s Cambridge Lectures (1858), further fueled public interest and led to the establishment of the Universities’ Mission to Central Africa in 1860, an initiative that Doctor Livingstone greatly anticipated for his second African expedition.