In 2005, science fiction television was forever changed with the revival of a beloved British classic, Doctor Who. To celebrate the enduring legacy of this incredible show, we’re revisiting some pivotal episodes, starting with “Rose,” the very first episode of the new series. This episode not only reintroduced the Doctor to a new generation but also expertly laid the foundation for years of thrilling adventures to come.

“So, I’m going to go up there and blow them up, and I might well die in the process, but don’t worry about me. No, you go home. Go on. Go and have your lovely beans on toast. Don’t tell anyone about this, because if you do, you’ll get them killed.

(beat)

I’m the Doctor, by the way. What’s your name?

Rose.

Nice to meet you, Rose. Run for your life!”

– The Doctor and Rose

It’s hard to overstate the sheer weight of expectation resting on “Rose.” After years off the air, and with only fan enthusiasm keeping the spirit of Doctor Who alive through books and audio dramas, a successful return to television felt like a distant dream. Enter Russell T. Davies, a writer known for groundbreaking dramas like Queer as Folk, not necessarily the obvious choice to helm the return of a family science fiction show. Yet, Davies, a long-time advocate for the Doctor’s comeback, had a vision. He had tirelessly campaigned for the show’s revival, finally bringing his passion project to screens in March 2005.

While “Rose” might show a few rough edges upon re-watching, it undeniably captures the spark that ignited the Doctor Who phenomenon once again. Davies cleverly draws inspiration from “Spearhead from Space,” another pivotal Doctor Who story that marked a significant shift for the series. Just as “Spearhead” relaunched Doctor Who with a new Doctor, in color, and on Earth, “Rose” reimagines the concept for a 21st-century audience.

The Ninth Doctor and Rose running from Autons.

The Ninth Doctor and Rose running from Autons.

The parallels with “Spearhead from Space” are indeed striking and purposeful. The transition from the Second to the Third Doctor in “Spearhead” was arguably the most transformative the show had ever undergone. It wasn’t just the switch to color; it was a complete tonal and thematic reset. The Pertwee era, launched by “Spearhead,” remains a benchmark for consistent, high-quality science fiction on the BBC. Davies, recognizing this impact, wisely chose “Spearhead” as a template for his revival.

Like “Spearhead,” “Rose” begins with a newly regenerated Doctor arriving on Earth, companion-less and ready for adventure. Both stories feature the terrifying Autons as villains, and both establish a season grounded, at least initially, on Earth. Christopher Eccleston’s Ninth Doctor also echoes Jon Pertwee’s Third Doctor in his initial demeanor. Both Doctors possess a certain gruffness and condescension towards humanity, yet harbor a deep, underlying affection for humankind.

Auton revealing its plastic face to Rose.

Auton revealing its plastic face to Rose.

The Autons themselves are a masterstroke of classic Doctor Who monster design. Despite only appearing twice in the original series, in consecutive season openers, they burrowed their way into the public consciousness. The Auton invasion depicted in “Terror of the Autons” remains an iconic, and at the time, controversial Doctor Who moment, even sparking concerns from media watchdog Mary Whitehouse.

The Autons perfectly embody the Doctor Who “sweet spot”: villains that are simultaneously absurdly camp and genuinely unsettling. The idea of everyday mannequins coming to life to kill is inherently ridiculous, yet the execution plunges them firmly into the uncanny valley. While some of the CGI in “Rose” might appear dated by today’s standards, the practical effects, particularly the makeup for the Auton duplicates like not!Mickey, are remarkably effective, rendering Noah Clarke unsettlingly plasticine.

Rose and the Doctor facing Autons in Henrik's.

Rose and the Doctor facing Autons in Henrik's.

However, while the Autons manage this tonal tightrope walk effectively, the episode itself occasionally stumbles. Doctor Who would quickly find its footing in balancing tone, but “Rose” sometimes veers too far into camp or seriousness. The Auton hand scene is undeniably the most overtly comedic moment in the revived series, and the visual effects showcasing the London Eye as a transmitter, or the sonic screwdriver’s capabilities, feel a tad heavy-handed.

Murray Gold’s score, while developing the orchestral grandeur that would become his signature, also struggles to find its balance in “Rose.” Later scores would be criticized for being overly bombastic, but Gold’s orchestral work generally adds wonderful scale to the show. Here, however, the music occasionally leans into synthesizer cheese, as if Gold was still experimenting with the new sonic palette available to him. Hints of the iconic themes to come are present, but the score in “Rose” feels like a work in progress, not yet fully formed.

Auton head with distorted plastic features.

Auton head with distorted plastic features.

Davies’ writing, a cornerstone of the revival’s success, is already on display, strengths and weaknesses alike. Having penned eight of the first season’s thirteen episodes, the initial season serves as a comprehensive showcase of his writing style. “Rose” immediately highlights his talent for character creation. The core cast – Rose, the Doctor, and even Mickey – feel remarkably well-defined in this pilot episode, despite Davies juggling an alien invasion plot within a tight 45-minute runtime.

Thematic depth is another Davies strength evident from the start. While the specifics are still veiled, the underlying emotional landscape is clear. The Doctor doesn’t explicitly mention the Time War in “Rose,” holding back that reveal until the following episode. Yet, it’s immediately apparent that this Doctor is grappling with profound trauma, experiencing a form of post-traumatic stress. Davies also subtly establishes the Doctor’s deep connection to Earth, hinting at its significance as his adopted home, a concept that would be explicitly explored later.

Christopher Eccleston as the Ninth Doctor in leather jacket.

Christopher Eccleston as the Ninth Doctor in leather jacket.

However, Davies’ strengths are counterbalanced by plotting inconsistencies, a trait that contrasts sharply with his successor, Steven Moffat. Moffat often excels at intricate plots, sometimes at the expense of character nuance. Davies, conversely, prioritizes character and theme, sometimes allowing plot details to become somewhat elastic. In “Rose,” attempting to cram so much into a short episode results in some plot conveniences and haziness.

For instance, the Autons’ ambush of Mickey outside Clive’s house feels contrived. If the Autons can convincingly replicate humans, why is their invasion force primarily comprised of shop dummies? The mechanics of their infiltration, beyond shop mannequins coming to life, remain vague. While the Doctor forces their hand, accelerating their invasion, the overall plot progression feels a little clunky at times.

The Doctor examining an Auton hand in Henrik's basement.

The Doctor examining an Auton hand in Henrik's basement.

Despite these narrative shortcomings, Davies excels at capturing the essential wonder and infectious enthusiasm that defines Doctor Who. Christopher Eccleston delivers perhaps the most cynical and world-weary Doctor to date, yet beneath the leather jacket and sardonic wit lies a deeply romantic soul.

Consider the Doctor’s poetic explanation of the universe to Rose:

“Do you know like we were saying about the Earth revolving? It’s like when you were a kid. The first time they tell you the world’s turning and you just can’t quite believe it because everything looks like it’s standing still. I can feel it. The turn of the Earth. The ground beneath our feet is spinning at a thousand miles an hour, and the entire planet is hurtling round the sun at sixty seven thousand miles an hour, and I can feel it. We’re falling through space, you and me, clinging to the skin of this tiny little world, and if we let go…

That’s who I am. Now, forget me, Rose Tyler. Go home.”

This is a masterful introduction to the character, conveying his essence without resorting to exposition dumps.

Close up of Auton face, distorted and inhuman.

Close up of Auton face, distorted and inhuman.

Davies’ script is remarkably economical with exposition about the Doctor’s identity and background. The Nestene Consciousness refers to him as “Timelord,” but there’s no clunky dialogue about Gallifrey or his past. Davies brilliantly unfolds these concepts gradually throughout the series, understanding that captivating the audience takes precedence over immediate backstory.

He introduces the Ninth Doctor without dwelling on the Eighth Doctor’s fate or even mentioning “regeneration.” Instead, he subtly conveys that the Doctor has undergone a profound change. “Rose” hints that this is the first time the Ninth Doctor has even seen his reflection. Long-time fans instantly grasp the implication of regeneration, while new viewers are simply intrigued by another layer of mystery.

The Ninth Doctor holding a sonic screwdriver, ready for action.

The Ninth Doctor holding a sonic screwdriver, ready for action.

This prioritization of character over plot mechanics is further illustrated by the Clive subplot. Clive presents Rose with photos of the Doctor at various historical events, including the eruption of Krakatoa, the JFK assassination, and the sinking of the Titanic. It strains credulity that the Doctor could travel through time to such significant events and not encounter a reflective surface. It feels like a narrative shortcut to quickly establish the Doctor’s long history, but the execution is a bit clumsy.

Mickey Smith as an Auton duplicate, menacing and plastic-like.

Mickey Smith as an Auton duplicate, menacing and plastic-like.

Despite these minor flaws, Eccleston’s Ninth Doctor remains a standout. For many, including myself, he is a favorite Doctor. His portrayal is unique because he is the only Doctor with a clearly defined character arc spanning his entire tenure. Only Peter Davison’s Fifth Doctor comes close in terms of a discernible arc.

Eccleston’s Doctor is strikingly human in his flaws. He’s glib, sarcastic, and cynical. While previous Doctors had their darker edges, the Ninth Doctor often comes across as genuinely abrasive. He frequently belittles Rose’s “little life” and curtly tells her to be quiet. “Are you going to witter on all night?” he snaps when she discovers Mickey is alive.

Rose and the Doctor standing outside Henrik's, London landmark in background.

Rose and the Doctor standing outside Henrik's, London landmark in background.

Even after neutralizing the not!Mickey duplicate, he neglects to immediately reassure Rose that the real Mickey might still be alive. “Yeah, that was always a possibility,” he concedes almost as an afterthought. This apparent callousness, however, reveals a deeper understanding of human emotion – a reluctance to offer false hope, a trait often absent in other Doctor iterations.

Simultaneously, this Doctor maintains an aloofness from humanity, perhaps too focused on the grand cosmic scale. The revived series emphasizes the role of human companions in grounding the Doctor, preventing him from becoming detached. In “Rose,” we already see Rose fulfilling this function:

“Look, if I did forget some kid called Mickey…

Yeah, he’s not a kid.

… it’s because I’m trying to save the life of every stupid ape blundering on top of this planet, all right?”

Eccleston’s performance conveys a palpable sense of desperation, a dramatic depth that was a brilliant choice for the show’s relaunch. While he may lack the overt charisma of Tennant, that is perhaps the point. Eccleston portrays a Doctor wrestling with loss and failure, burdened by the unspoken horrors of the Time War. Even before the full extent of the “Last Great Time War” is revealed in “The End of Time,” it’s clear this Doctor carries immense emotional baggage.

Rose Tyler looking determined and ready for adventure.

Rose Tyler looking determined and ready for adventure.

This portrayal raises fascinating questions. Is the Ninth Doctor truly responsible for the events of the Time War? Considering he doesn’t even recognize his own face, it suggests the Eighth Doctor bore the brunt of the conflict. Can the Ninth Doctor be held accountable for decisions made by a past incarnation? All Doctors are the same person, yet distinctly different. Eccleston embodies a Doctor born into guilt, a powerful and nuanced performance.

This desperation surfaces even in his first appearance. No other Doctor has seemed quite as broken as Eccleston’s, pleading for a non-violent resolution. Even armed with a weapon to destroy the Nestene, he implores, “This planet is just starting. These stupid little people have only just learnt how to walk, but they’re capable of so much more. I’m asking you on their behalf. Please, just go.” He yearns for the “everybody lives!” moment that finally arrives in “The Doctor Dances.”

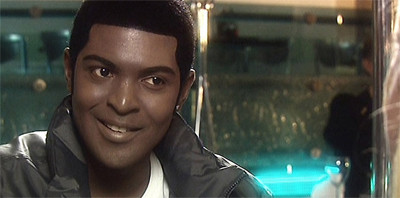

The Ninth Doctor smiling, a rare and precious moment.

The Ninth Doctor smiling, a rare and precious moment.

Even his invitation to Rose feels tinged with neediness. “What do you think?” he asks. “You could stay here, fill your life with work and food and sleep, or you could go anywhere.” His initial dismissal of Mickey feels deliberate. He even returns to Rose for a second invitation, highlighting his desire for companionship. In a nice foreshadowing of “Father’s Day,” it’s this second invitation, coupled with the revelation of time travel, that ultimately convinces Rose. “By the way, did I mention it also travels in time?”

However, despite the Doctor’s compelling presence, the episode truly belongs to Rose. Her name graces the title, and we experience the Doctor’s reintroduction through her eyes, echoing Ian and Barbara’s introduction to the First Doctor fifty years prior. While Rose’s character arc might have eventually overstayed its welcome for some, her initial conception was remarkably clever.

Billie Piper as Rose Tyler, looking thoughtful and curious.

Billie Piper as Rose Tyler, looking thoughtful and curious.

While classic Doctor Who featured contemporary companions, particularly during the Third Doctor era, we rarely delved into their personal lives and circumstances. Companions seemed to seamlessly enter and exit the Doctor’s world without significant impact on their everyday lives. Rose, for the first time, is presented as a character with roots, a background, an established life. She isn’t just a blank slate ready to jump into a spaceship without anyone noticing her absence.

This concept was, and remains, groundbreaking. While the series might have explored this “modern companion” trope a bit too extensively in subsequent years, it was a brilliant innovation in the show’s first season back. It acknowledged that the world, and television itself, had evolved during Doctor Who’s absence, and Davies embraced that change.

Autons standing amongst mannequins, blending into their surroundings.

Autons standing amongst mannequins, blending into their surroundings.

More profoundly, Rose allows Davies to explore the very essence of the Doctor as a concept. While Moffat would later emphasize the Doctor as a whimsical, almost childlike imaginary friend, Davies initially portrays him as a figure of romantic fantasy. The Doctor is someone who descends from the sky and whisks you away on incredible adventures. He expands your horizons, reveals the impossible, and offers escape from the mundane.

Rose is immediately and effectively established as working class. She lives in a council flat in London and works in a department store. After her workplace is destroyed, her options are limited and ordinary. “Do you think I should try the hospital?” she asks Mickey. “Suki said they had jobs going in the canteen. Is that it then, dishing out chips. I could do A Levels. I don’t know. It’s all Jimmy Stone’s fault. I only left school because of him. Look where he ended up.” For Rose, more than anyone, the Doctor represents the extraordinary, the escape from the ordinary.

Christopher Eccleston and Billie Piper in Doctor Who: Rose.

Christopher Eccleston and Billie Piper in Doctor Who: Rose.

As an aside, Mickey’s initial portrayal as a less-than-ideal boyfriend is noteworthy. His posturing in front of Clive is comical, but he’s presented as quite possibly the worst boyfriend imaginable. After Rose’s workplace explodes, he checks in briefly, only to rush off to the pub for the last five minutes of a football match. While this makes Rose’s decision to leave him easier for the audience to accept, it feels like somewhat convenient characterization. Fortunately, Mickey’s character would undergo significant development in later episodes.

The episode’s climax beneath the London Eye is also well-executed. The set design is suitably mundane for an alien invasion headquarters, echoing the resourceful location choices of classic Doctor Who. It’s a reminder that even with a larger budget and modern sensibilities, Doctor Who retained its connection to its roots.

Auton attacking Mickey in the basement of Henrik's.

Auton attacking Mickey in the basement of Henrik's.

“Rose” may not be the absolute pinnacle of the season, but it is a remarkably strong starting point. While some elements feel slightly unpolished, and the tonal balance is still being refined, it successfully introduces the new cast and tells a compelling alien invasion story within a 45-minute timeframe. More importantly, “Rose” showcases the immense potential of the revived Doctor Who, setting the stage for the fantastic adventures that were to follow.