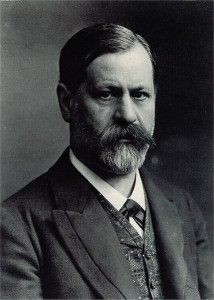

Sigmund Freud, widely recognized as the father of psychoanalysis, was not only a groundbreaking psychologist but also a trained physiologist and medical doctor. His journey from a medical doctor in Vienna to an influential thinker who revolutionized the understanding of the human mind is a fascinating study in intellectual evolution. Freud’s initial training as a medical doctor significantly shaped his theories and therapeutic approaches, providing a foundation for his exploration of the unconscious, infantile sexuality, and the structure of the mind. His work, though debated, has indelibly impacted fields ranging from psychology and anthropology to art and literature.

Sigmund Freud

Sigmund Freud

1. Life of a Doctor Turned Psychoanalyst

Born in Frieberg, Moravia, in 1856, Sigmund Freud’s family relocated to Vienna when he was four, a city that would become synonymous with his life and work. Vienna was where Freud established the first Viennese school of psychoanalysis, a movement that spurred countless developments in the field. Despite his broad intellectual curiosity, Freud initially pursued science. Driven by a desire to expand human knowledge, rather than solely practice medicine, he enrolled in the medical school at the University of Vienna in 1873.

Freud’s early academic focus was biology. He dedicated six years to physiological research under the esteemed German scientist Ernst Brücke, the director of the Physiology Laboratory at the University. Later, Freud specialized in neurology, earning his medical degree in 1881. By 1882, engagement prompted him to seek more stable employment. This led him to Vienna General Hospital, where he worked as a doctor, a financially more secure path. In 1886, following a happy marriage that blessed him with six children, including Anna Freud, who also became a renowned psychoanalyst, Freud established a private practice. It was in this practice, treating psychological disorders, that he amassed the clinical observations that would underpin his revolutionary theories and pioneering therapeutic techniques.

A pivotal year in Freud’s development as a future psychoanalyst was 1885-86 when he spent a significant period in Paris. There, he was profoundly influenced by Jean Charcot, a distinguished French neurologist who was using hypnotism to treat hysteria and other mental conditions. Upon returning to Vienna, Dr. Freud experimented with hypnosis himself. However, finding its effects temporary, he shifted towards a method proposed by Josef Breuer, an older Viennese colleague and friend. Breuer had observed that encouraging a patient with hysteria to speak openly about the origins of their symptoms sometimes led to their gradual reduction.

Collaborating with Breuer, Dr. Freud developed the concept that many neuroses, such as phobias, hysterical paralysis, pains, and certain forms of paranoia, stemmed from deeply traumatic past experiences, forgotten and hidden in the unconscious. The therapeutic approach, they theorized, was to help patients bring these experiences into conscious awareness. By confronting these traumas intellectually and emotionally, patients could discharge their emotional burden, thereby addressing the psychological roots of their neurotic symptoms. This method and its theoretical foundation were detailed in Studies in Hysteria, published jointly by Freud and Breuer in 1895.

However, their collaboration was short-lived. Breuer disagreed with what he perceived as Freud’s overemphasis on the sexual origins of neuroses. This divergence led to their separation, with Freud continuing to refine his psychoanalytic theory and practice independently. In 1900, after extensive self-analysis, Freud published The Interpretation of Dreams, widely considered his magnum opus. This was followed by The Psychopathology of Everyday Life in 1901, and Three Essays on the Theory of Sexuality in 1905. Initially, Freud’s psychoanalytic theories faced considerable resistance. Public and professional reception was often scandalized by his focus on sexuality, as Breuer had predicted.

It wasn’t until 1908, at the first International Psychoanalytical Congress in Salzburg, that Freud’s significance began to gain broader recognition. This recognition was further boosted in 1909 when he was invited to lecture in the United States, lectures that formed the basis of his 1916 book, Five Lectures on Psycho-Analysis. From this point forward, Freud’s reputation and influence grew exponentially. He continued to write prolifically until his death, producing over twenty volumes of theoretical works and clinical studies. Notably, Freud was open to revising his perspectives, even fundamentally altering core principles when scientific evidence warranted. This adaptability is evident in his 1923 work, The Ego and the Id, which introduced a new tripartite model of the mind (id, ego, and super-ego).

Although initially encouraged by the intellectual caliber of early followers like Adler and Jung, Freud was disheartened when they established rival psychoanalytic schools, marking the first of many divisions within the movement. Nevertheless, he recognized that such disagreements were inherent in the early stages of any new scientific discipline. After a remarkably productive life, Sigmund Freud, the medical doctor who became the father of psychoanalysis, passed away from cancer in exile in England in 1939.

2. The Intellectual Landscape Shaping Freud’s Thought

While Sigmund Freud was an exceptionally original thinker, his work was also deeply rooted in and influenced by a range of contemporary factors. Jean Charcot and Josef Breuer had immediate and direct impacts on his thinking, but other influences, while less direct, were equally significant. Notably, Freud’s own personality and experiences, including his background as a medical doctor trained in scientific rigor, played a crucial role.

Freud’s self-analysis, which is central to The Interpretation of Dreams, emerged from an emotional crisis following his father’s death and the dreams it provoked. This introspection led him to discover ambivalent feelings towards his father – a mix of love and admiration intertwined with shame and resentment. He also uncovered a childhood fantasy involving his half-brother Philip, who was close in age to his mother, suggesting a repressed desire to replace his father in his mother’s affections. These personal insights became the basis for his theory of the Oedipus complex, though Freud emphasized it was not exclusively based on his own experience.

More broadly, the scientific climate of the 19th century significantly shaped Freud’s views. Charles Darwin, with his theory of evolution presented in Origin of Species, was the dominant scientific figure. Darwin’s work revolutionized the understanding of humanity, shifting from a view of humans as inherently different from animals due to an immortal soul, to seeing humans as part of the natural world. This paradigm shift allowed for the scientific study of human behavior and motivations, which Freud embraced. His medical and scientific training made him predisposed to seek biological and evolutionary underpinnings for psychological phenomena.

An even more profound influence stemmed from the field of physics. The latter half of the 19th century witnessed significant advancements in physics, largely initiated by Hermann von Helmholtz’s formulation of the principle of conservation of energy. This principle, stating that the total energy in a closed system remains constant, revolutionized fields like thermodynamics and electromagnetism. Ernst Brücke, under whom Freud studied, applied this principle to biology in his Lecture Notes on Physiology, arguing that all living organisms, including humans, are essentially energy-systems governed by the conservation of energy.

Freud, deeply respecting Brücke, enthusiastically adopted this dynamic physiology. He took a crucial conceptual leap, informed by his medical and scientific background, to propose the existence of psychic energy. He posited that the human personality is also an energy-system, and psychology’s role is to investigate the transformations and movements of psychic energy within the personality. This concept became the cornerstone of Freud’s psychoanalytic theory, framing the human mind in mechanistic, energy-driven terms, much like the physiological processes he studied as a medical doctor.

3. The Unconscious Mind: A Doctor’s Deterministic View

Freud’s theory of the unconscious is fundamentally deterministic, a perspective that aligns with the scientific views of the 19th century and his own medical training which emphasized cause-and-effect relationships. Freud was arguably the first to systematically apply deterministic principles to the mental realm, asserting that human behavior is explicable through underlying, often hidden, mental processes. This was a significant departure from prevailing views that often treated neurotic behavior as inexplicable. Instead, Freud, the medically trained doctor, insisted on seeking explanations and causes for such behavior within the individual’s mental state.

This deterministic approach explains Freud’s interest in seemingly trivial phenomena like slips of the tongue, obsessive behaviors, and dreams. He viewed these as manifestations of hidden mental causes, revealing unconscious processes that would otherwise remain unknown. This perspective inherently questions the extent of free will, suggesting that choices are often governed by unconscious processes beyond conscious control.

The very idea of unconscious mental states stems from Freud’s determinism. He reasoned that causality necessitates the existence of such states to explain behaviors that have no apparent cause in the conscious mind. For Freud, an unconscious mental process is not merely out of awareness but actively prevented from reaching consciousness, except through the rigorous process of psychoanalysis. This implies that the mind cannot be equated with consciousness. Instead, Freud famously likened the mind to an iceberg, with the conscious mind being only the visible tip, while the vast, submerged unconscious exerts a powerful, unseen influence.

Integral to Freud’s model of the mind are instincts or drives. He saw instincts as the primary motivating forces, energizing all mental functions. While acknowledging a vast array of instincts, Freud categorized them into two primary groups: Eros (the life instinct) encompassing self-preservation and erotic instincts, and Thanatos (the death instinct) which includes aggression, self-destruction, and cruelty. It’s crucial to note that Freud did not claim all actions are sexually motivated. Thanatos, for instance, represents a drive distinct from sexual motivations.

However, Freud undeniably emphasized sexuality’s central role in human life, actions, and behavior, a novel and often shocking proposition for his time. He argued for the existence of sexual drives in children from birth (infantile sexuality) and identified sexual energy (libido) as a dominant motivating force throughout life. Crucially, Freud broadened the definition of sexuality to encompass any form of bodily pleasure. Thus, his theory of drives essentially posits that humans are driven from birth by a desire to seek and maximize bodily pleasure. This perspective, rooted in his medical understanding of biological drives, formed a cornerstone of his psychoanalytic framework.

4. Infantile Sexuality: A Developmental Perspective from a Doctor’s Eye

Freud’s theory of infantile sexuality is integral to his broader developmental theory of personality. It originated from, and generalized, Breuer’s discovery that childhood traumas could have lasting negative impacts on adults. Freud extended this, proposing that early childhood sexual experiences are critical in shaping adult personality. This perspective was likely influenced by his medical background, which emphasized developmental stages and the impact of early experiences on later health.

Building on his theory of drives, Freud posited that from birth, infants are driven by the pursuit of bodily/sexual pleasure, viewed in mechanistic terms as the release of mental energy. Initially, infants derive pleasure from sucking, which Freud termed the oral stage. This is followed by the anal stage, where pleasure is associated with the anus, particularly during defecation. Subsequently, children develop an interest in their genitals as a source of pleasure, marking the phallic stage. During this stage, the Oedipus complex emerges: a deep sexual attraction towards the opposite-sex parent and rivalry with the same-sex parent.

However, the Oedipus complex leads to socially derived guilt, as the child recognizes their inability to supplant the stronger parent. Male children also experience castration anxiety, fearing potential harm from the father if they persist in their attraction to the mother. These feelings, along with the Oedipal desires, are typically repressed. The child resolves the Oedipus complex around age five by identifying with the same-sex parent, entering a latency period where sexual motivations become less pronounced until puberty. Puberty marks the onset of mature genital development, and the pleasure drive refocuses on the genital area.

Freud considered this progression as the typical course of human development. He noted that parental control and social norms frequently check infants’ instinctual drives for pleasure. Development, therefore, is a series of conflicts. Successful resolution of these conflicts is crucial for adult mental health. Freud believed that many mental illnesses, especially hysteria, originate from unresolved conflicts or disruptions during these early stages. For example, some Freudians link homosexuality to unresolved Oedipal conflicts, particularly a failure to identify with the same-sex parent. Obsessive behaviors like excessive handwashing are seen as stemming from unresolved conflicts during the anal stage. This stage-based, conflict-driven model of development, while psychological, echoes developmental frameworks common in medical and biological sciences of Freud’s time.

5. Neuroses and the Mind’s Structure: A Doctor’s Model

Freud’s understanding of the unconscious and his psychoanalytic therapy are best illustrated by his tripartite model of the mind, developed in 1923, though foreshadowed by Plato’s similar concepts over two millennia prior. This model, likely influenced by Freud’s medical training to categorize and structure complex systems, divides the mind into three interacting components: id, ego, and super-ego.

The id is the reservoir of instinctual drives, primarily sexual, demanding immediate gratification. The super-ego embodies the conscience, incorporating internalized social and parental control mechanisms. The ego, the conscious self, arises from the dynamic interplay between the id and super-ego, mediating their conflicting demands with external reality. This model represents the mind as a dynamic energy-system, consistent with Freud’s earlier adoption of dynamic physiology.

Conscious experiences reside in the ego. The id’s contents remain unconscious, while the super-ego acts as an unconscious censor, attempting to control the id’s pleasure-seeking impulses through restrictive rules. While the literal interpretation of this model is debated, it serves as a theoretical framework for understanding the link between childhood experiences and adult personality, both normal and dysfunctional. Freud himself seemed to view it quite literally, using it as a diagnostic and therapeutic tool, much like a medical model.

Freud, like Plato, equated mental health with harmony among these three elements. Conflict arises when the external world or the super-ego obstructs the id’s pleasure drives. Unresolved conflicts can lead to neuroses. Freud proposed that the mind employs defense mechanisms to mitigate acute conflicts. These include repression (pushing conflicts into the unconscious), sublimation (channeling sexual drives into socially acceptable pursuits like art or science), fixation (failure to progress beyond a developmental stage), and regression (reverting to earlier stage behaviors).

Repression is central. It occurs when an impulse deemed reprehensible by the super-ego, such as a child’s erotic desire for a parent, is pushed into the unconscious. Repression is a normal defense mechanism, integral to development. However, repressed drives, as energy forms, are not eliminated. They persist in the unconscious, influencing the conscious mind and causing neurotic behaviors. This explains the symbolic significance Freud attributed to dreams and slips of the tongue, seen as instances where the super-ego’s vigilance relaxes, allowing repressed drives to surface in disguised forms.

The distinction between normal and neurotic repression is one of degree. Neurotic symptoms are manifestations of repressed drives, irrational and uncontrollable because they stem from unconscious impulses. Freud located the key repressions, for both normal and neurotic individuals, in the first five years of life, primarily sexual in nature. Disruptions in infantile sexual development, he argued, strongly predispose individuals to later neuroses. Psychoanalytic therapy aims to uncover these repressions, bringing them to conscious awareness so the ego can confront and resolve them. This process of uncovering and resolving unconscious conflicts, while psychological, mirrors a doctor’s approach to diagnosing and treating hidden ailments.

6. Psychoanalysis as Therapy: The Doctor’s “Talking Cure”

Freud’s understanding of neuroses as rooted in sexual origins naturally led to his development of psychoanalysis as a clinical treatment. Today, psychoanalysis often refers solely to this therapy, but it correctly encompasses both the treatment and its underlying theory. The therapy’s goal is to restore harmony among the id, ego, and super-ego by uncovering and resolving repressed unconscious conflicts.

Freud’s therapeutic method evolved from Breuer’s earlier work. Breuer had observed that allowing a hysterical patient to talk freely about symptom origins and fantasies alleviated symptoms, especially when they recalled the initial trauma. Moving beyond hypnosis, Freud developed this “talking cure,” based on the premise that repressed conflicts are deeply buried in the unconscious.

He instructed patients to relax, minimizing sensory stimulation and direct awareness of the analyst (hence the couch, with the analyst out of sight and largely silent). He encouraged free, uninhibited speech, ideally without premeditation, believing this would reveal unconscious forces. This free association method, similar to dream analysis, aims to bypass the super-ego’s censorship, allowing repressed material to reach the conscious ego.

Psychoanalysis is necessarily lengthy and challenging. A key analyst role is to help patients recognize and overcome their resistances, which may manifest as hostility towards the analyst. Freud viewed resistance as a positive sign, indicating proximity to the underlying unconscious causes. Patient dreams are particularly valuable. Freud distinguished between a dream’s manifest content (surface appearance) and latent content (unconscious desires). Analyzing dreams, slips of the tongue, free associations, and responses to questions, the analyst aims to pinpoint the unconscious repressions causing neurotic symptoms. These are invariably linked to the patient’s psychosexual development, conflict management, and family relationships.

Therapeutic success, for Freud, hinges on facilitating patient self-understanding. Once conscious of these unconscious forces, the patient, with the analyst, decides how to manage this understanding. Options include sublimation, channeling sexual energy into creative or socially valuable activities, which Freud saw as driving cultural achievements. Another is suppression, consciously controlling formerly repressed drives. Alternatively, a patient might conclude that societal constraints are the issue and choose to satisfy instinctual drives. In all cases, the cure involves catharsis, a release of pent-up psychic energy whose constriction caused the neurosis. This therapeutic approach, while psychological, shares similarities with medical treatments aimed at removing blockages or imbalances within a system.

7. Critical Evaluation of Freud: Doctor of the Mind Under Scrutiny

Freud and psychoanalysis have profoundly influenced Western thought and culture, yet remain highly controversial. The debate around Freud is intense, perhaps second only to Darwin among post-1850 thinkers. Criticisms range from questioning Freud’s methodology due to alleged cocaine addiction (Thornton, Freud and Cocaine: The Freudian Fallacy) to suggesting he suppressed a grim discovery for social acceptance (Masson, The Assault on Truth).

While Freud’s genius is generally acknowledged, the nature of his achievement is debated. Supporters often display fervent zeal, resembling a secular religion, requiring analyst-in-training to undergo personal analysis. Critics argue this fosters ideological conformity. Psychoanalytic proponents often analyze critics’ motivations through a Freudian lens, perpetuating the debate.

This evaluation focuses on: (a) Freud’s claim to scientific status, (b) theory coherence, (c) Freud’s actual discoveries, and (d) psychoanalytic therapy efficacy.

a. Scientific Status: Doctor or Dogmatist?

Freud viewed himself as a pioneering scientist, asserting psychoanalysis as a new science with a novel method for studying the mind and mental illness. This scientific claim is a major draw for proponents, who see psychoanalysis as a robust, comprehensive theory explaining all human behavior. However, this very comprehensiveness raises questions about its scientific validity. Karl Popper’s demarcation criterion, widely accepted, states that scientific theories must be testable and falsifiable. A scientific theory is incompatible with possible observations; a theory compatible with all observations is unscientific (Popper, The Logic of Scientific Discovery).

The principle of energy conservation, influential to Freud, is scientific because it’s falsifiable. Discovering a system violating energy conservation would disprove it. Critics argue Freud’s theory is unfalsifiable. Asked what could disprove psychoanalysis, the answer is arguably “nothing,” as it can accommodate any observation. Therefore, critics conclude, psychoanalysis is unscientific. This doesn’t negate its value, but weakens its claim as a science, as Freud and advocates presented it.

b. Theory Coherence: Is the Doctor’s Diagnosis Sound?

The coherence of psychoanalytic theory is also questionable. Its appeal lies in offering causal explanations for mental distress. The idea that neuroses arise from unconscious conflicts of repressed libidinal energy seems to provide insight into the causal mechanisms of mental illness, linking them to normal psychology. However, this is debated. Causality typically requires independently identifiable cause (X) and effect (Y). While causes can be unobservable in science (e.g., subatomic particles), correspondence rules link unobservable causes to observable phenomena.

Freud’s theory posits unobservable causes (e.g., repressed unconscious conflicts) for behaviors. But there are no clear correspondence rules. These causes are identified only through the behaviors they are supposed to explain. The analyst doesn’t demonstrate, “This is the unconscious cause, and that is the effect,” but infers, “This is the behavior, therefore an unconscious cause must exist.” This circularity casts doubt on whether psychoanalysis offers genuine causal explanations.

c. Freud’s Discovery: Uncovering Truth or Constructing Theory?

Critics like Masson (The Assault on Truth) suggest Freud made a genuine discovery—widespread child sexual abuse—but suppressed it due to hostile reactions, replacing it with the theory of the unconscious. Freud initially proposed a seduction theory of neuroses, which faced fierce opposition and was quickly retracted in favor of unconscious conflicts. As one Freudian commentator notes:

“Questions concerning the traumas suffered by his patients seemed to reveal [to Freud] that Viennese girls were extraordinarily often seduced in very early childhood by older male relatives. Doubt about the actual occurrence of these seductions was soon replaced by certainty that it was descriptions about childhood fantasy that were being offered” (MacIntyre).

This suggests the Oedipus complex emerged as a substitute. The term “extraordinarily often” raises questions: what standard is used? Critics argue Freud’s patients weren’t recalling fantasies but real traumatic events. Freud, they contend, knowingly suppressed the reality of widespread child sexual abuse. If true, this is a severe indictment.

This issue gains further controversy with contemporary Freudians combining repression theory with the acknowledgement of widespread child sexual abuse. This has led to “recovered memories” of abuse in therapy, causing accusations, family divisions, and the “False Memory Syndrome” backlash (Pendergast, Victims of Memory). The concept of repression, “the foundation stone of psychoanalysis,” faces unprecedented scrutiny. It’s often overlooked that Freud himself didn’t extend repression to actual child sexual abuse, and that not all recovered memories are necessarily veridical or falsidical. The debate is intensely polarized.

d. Therapy Efficacy: Does the Doctor’s Cure Work?

Even if Freud’s theory is unscientific or false, it might still be therapeutically beneficial. A theory’s truth and utility are not directly correlated. Eighteenth-century leeching was based on flawed theory, yet sometimes helped patients. Conversely, a true theory can be misapplied. Defining “cure” for neurosis is complex, distinguishing it from symptom alleviation.

Therapeutic efficacy is typically measured using control groups, comparing outcomes of treatment X to other treatments or no treatment. Clinical trials suggest psychoanalytic treatment outcomes are not significantly different from spontaneous recovery or other interventions in control groups. Thus, psychoanalysis’s therapeutic effectiveness remains debated and unproven by robust empirical evidence.

8. References and Further Reading

a. Works by Freud

- The Standard Edition of the Complete Psychological Works of Sigmund Freud (Ed. J. Strachey with Anna Freud), 24 vols. London: 1953-1964.

b. Works on Freud and Freudian Psychoanalysis

- Abramson, J.B. Liberation and Its Limits: The Moral and Political Thought of Freud. New York: Free Press, 1984.

- Bettlelheim, B. Freud and Man’s Soul. Knopf, 1982.

- Cavell, M. The Psychoanalytic Mind: From Freud to Philosophy. Harvard University Press, 1993.

- Cavell, M. Becoming a Subject: Reflections in Philosophy and Psychoanalysis. New York: Oxford University Press, 2006.

- Chessick, R.D. Freud Teaches Psychotherapy. Hackett Publishing Company, 1980.

- Cioffi, F. (ed.) Freud: Modern Judgements. Macmillan, 1973.

- Deigh, J. The Sources of Moral Agency: Essays in Moral Psychology and Freudian Theory. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press, 1996.

- Dilman, I. Freud and Human Nature. Blackwell, 1983

- Dilman, I. Freud and the Mind. Blackwell, 1984.

- Edelson, M. Hypothesis and Evidence in Psychoanalysis. University of Chicago Press, 1984.

- Erwin, E. A Final Accounting: Philosophical and Empirical Issues in Freudian Psychology. MIT Press, 1996.

- Fancher, R. Psychoanalytic Psychology: The Development of Freud’s Thought. Norton, 1973.

- Farrell, B.A. The Standing of Psychoanalysis. Oxford University Press, 1981.

- Fingarette, H. The Self in Transformation: Psychoanalysis, Philosophy, and the Life of the Spirit. HarperCollins, 1977.

- Freeman, L. The Story of Anna O.—The Woman who led Freud to Psychoanalysis. Paragon House, 1990.

- Frosh, S. The Politics of Psychoanalysis: An Introduction to Freudian and Post-Freudian Theory. Yale University Press, 1987.

- Gardner, S. Irrationality and the Philosophy of Psychoanalysis. Cambridge, Cambridge University Press, 1993.

- Grünbaum, A. The Foundations of Psychoanalysis: A Philosophical Critique. University of California Press, 1984.

- Gay, V.P. Freud on Sublimation: Reconsiderations. Albany, NY: State University Press, 1992.

- Hook, S. (ed.) Psychoanalysis, Scientific Method, and Philosophy. New York University Press, 1959.

- Jones, E. Sigmund Freud: Life and Work (3 vols), Basic Books, 1953-1957.

- Klein, G.S. Psychoanalytic Theory: An Exploration of Essentials. International Universities Press, 1976.

- Lear, J. Love and Its Place in Nature: A Philosophical Interpretation of Freudian Psychoanalysis. Farrar, Straus & Giroux, 1990.

- Lear, J. Open Minded: Working Out the Logic of the Soul. Cambridge, Harvard University Press, 1998.

- Lear, Jonathan. Happiness, Death, and the Remainder of Life. Harvard University Press, 2000.

- Lear, Jonathan. Freud. Routledge, 2005.

- Levine, M.P. (ed). The Analytic Freud: Philosophy and Psychoanalysis. London: Routledge, 2000.

- Levy, D. Freud Among the Philosophers: The Psychoanalytic Unconscious and Its Philosophical Critics. New Haven, CT: Yale University Press, 1996.

- MacIntyre, A.C. The Unconscious: A Conceptual Analysis. Routledge & Kegan Paul, 1958.

- Mahony, P.J. Freud’s Dora: A Psychoanalytic, Historical and Textual Study. Yale University Press, 1996.

- Masson, J. The Assault on Truth: Freud’s Suppression of the Seduction Theory. Faber & Faber, 1984.

- Neu, J. (ed). The Cambridge Companion to Freud. Cambridge University Press, 1994.

- O’Neill, J. (ed). Freud and the Passions. Pennsylvania State University Press, 2004.

- Popper, K. The Logic of Scientific Discovery. Hutchinson, 1959.

- Pendergast, M. Victims of Memory. HarperCollins, 1997.

- Reiser, M. Mind, Brain, Body: Towards a Convergence of Psychoanalysis and Neurobiology. Basic Books, 1984.

- Ricoeur, P. Freud and Philosophy: An Essay in Interpretation (trans. D. Savage). Yale University Press, 1970.

- Robinson, P. Freud and His Critics. Berkeley, University of California Press, 1993.

- Rose, J. On Not Being Able to Sleep: Psychoanalysis and the Modern World. Princeton University Press, 2003.

- Roth, P. The Superego. Icon Books, 2001.

- Rudnytsky, P.L. Freud and Oedipus. Columbia University Press, 1987.

- Said, E.W. Freud and the Non-European. Verso (in association with the Freud Museum, London), 2003.

- Schafer, R. A New Language for Psychoanalysis. Yale University Press, 1976.

- Sherwood, M. The Logic of Explanation in Psychoanalysis. Academic Press, 1969.

- Smith, D.L. Freud’s Philosophy of the Unconscious. Kluwer, 1999.

- Stewart, W. Psychoanalysis: The First Ten Years, 1888-1898. Macmillan, 1969.

- Sulloway, F. Freud, Biologist of the Mind. Basic Books, 1979.

- Thornton, E.M. Freud and Cocaine: The Freudian Fallacy. Blond & Briggs, 1983.

- Tauber, A.I. Freud, the Reluctant Philosopher. Princeton University Press, 2010.

- Wallace, E.R. Freud and Anthropology: A History and Reappraisal. International Universities Press, 1983.

- Wallwork, E. Psychoanalysis and Ethics. Yale University Press, 1991.

- Whitebrook, J. Perversion and Utopia: A Study in Psychoanalysis and Critical Theory. MIT Press, 1995.

- Whyte, L.L. The Unconscious Before Freud. Basic Books, 1960.

- Wollheim, R. Freud. Fontana, 1971.

- Wollheim, R. (ed.) Freud: A Collection of Critical Essays. Anchor, 1974.

- Wollheim, R. & Hopkins, J. (eds.) Philosophical Essays on Freud. Cambridge University Press, 1982.

See also the articles on Descartes’ Mind-Body Distinction, Higher-Order Theories of Consciousness and Introspection.

Author Information

Stephen P. Thornton University of Limerick Ireland