It started with a voicemail, a cheerful voice informing me of my prestigious “Top Doctor” award. The catch? I’m not a doctor. As an investigative journalist specializing in healthcare at ProPublica, my expertise lies in scrutinizing the medical system, not practicing within it. This unexpected recognition from a Long Island-based company, Top Doctor Awards, sparked my curiosity and set me on a path to uncover the truth behind these ubiquitous accolades.

Initially, the call seemed absurd, easily dismissed as a misguided sales pitch. However, I recognized a deeper issue at play. These awards tap into the complex relationship between doctors’ professional pride and patients’ urgent quest for quality healthcare. Many patients, understandably, assume these “Top Doctor” titles signify rigorous evaluation and represent genuinely superior physicians. This perception is reinforced when hospitals and doctors proudly display these awards, lending an air of legitimacy to what might be a hollow honor.

The fact that Top Doctor Awards mistakenly identified me, someone entirely outside the medical profession, as worthy of their accolade was both ironic and telling. For over a decade, I’ve been investigating healthcare, focusing on the often-murky area of doctor quality assessment. Determining a physician’s true competence – considering factors from diagnostic skills to surgical outcomes and patient satisfaction – is a profoundly complex endeavor. Yet, a booming industry of for-profit companies churns out “Top,” “Super,” and “Best” doctor lists, readily marketed through magazine ads, online directories, and, of course, those coveted plaques and promotional videos – often available for an additional fee.

During my call with Anne from Top Doctor Awards, the conversation took an unexpected turn when she finally noticed my affiliation.

“It says here you work for a company called ProPublica,” she stated, finally reading my details correctly.

“Yes,” I replied, “and I’m actually a journalist, not a doctor. Is that going to be a problem for my ‘Top Doctor’ award?” I asked, genuinely curious.

A moment of stunned silence followed. Clearly, my profession was an unforeseen variable in her sales script. But quickly recovering, Anne declared, “No,” I could still receive the award.

It became apparent that Anne’s sales targets likely prioritized quantity over quality of award recipients.

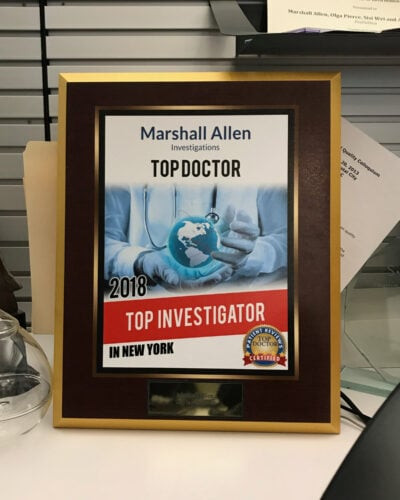

Then came the sales pitch. The “honor” included a personalized plaque, offered in classic cherry wood with gold trim or contemporary black with chrome. I pondered which aesthetic best represented my unique brand of “medicine”—investigative journalism.

“There’s a nominal fee for this recognition,” Anne continued, slipping back into her scripted cadence. “A reduced rate, just $289. We accept Visa, Mastercard, and American Express.”

Even for a unique reporting expense, $289 felt steep for ProPublica’s budget. I hesitated.

“This plaque celebrates your achievements and, more importantly, communicates those achievements to your patients,” she emphasized, moving towards closing the deal. “It’s a significant accomplishment. I wouldn’t want you to miss out. I can offer it to you right now for $99.”

I accepted the discounted offer, and just like that, I became a “Top Doctor.” It certainly seemed a much quicker route than medical school and years of residency. And, I must admit, it did lend a certain authority when advising colleagues in the newsroom, “Maybe you should go home before we all catch your cold.”

My experience with Top Doctor Awards, while amusing, raised serious questions about the legitimacy of the numerous doctor accolades we encounter. From Castle Connolly Top Doctors to Super Doctors and The Best Docs, the market is saturated with these titles. The more I investigated, the more companies I discovered bestowing praise upon physicians, only to then charge them to promote their “achievement.” What criteria were they truly using? And what motivated doctors to participate in this system? I wondered how these “real” doctors would react to learning about my equally esteemed “Top Doctor” status.

First, I sought insights from actual healthcare quality experts. Their reactions were, unsurprisingly, critical. “This is a scam,” declared Dr. Michael Carome, director of the health research group at Public Citizen, a consumer advocacy organization. “Any truly competent and qualified doctor doesn’t need one of these awards, unless they are simply seeking an ego boost. These awards are meaningless and worthless.”

Dr. Carome went further, suggesting it was unethical for companies to issue these awards and for doctors to accept them.

Conversely, the companies behind these for-profit doctor ratings were quick to defend their legitimacy, often at the expense of their competitors.

John Connolly, co-founder of Castle Connolly Top Doctors, couldn’t resist a jab at my award. “What’s your specialty, Dr. Marshall?” he joked. “I hope you’re not performing surgery.”

Connolly explained that his company relies on peer nominations to identify “top doctors.” He stated they have a research team that verifies each nominee’s license, board certification, education, and disciplinary history. While these checks are basic and publicly accessible, they would, at least, prevent someone like me from slipping through the cracks.

Connolly conceded that gaming the nomination system would be “very difficult” but offered a notable disclaimer. “We don’t claim they are the best,” he clarified regarding Castle Connolly honorees. “We say they are ‘among the best’ and ones we have screened carefully.”

Doctors recognized as “among the best” by Castle Connolly can enhance their online presence with upgraded profiles in the company’s directory. They can also purchase plaques to display their achievement. Further revenue is generated through partnerships with magazines for promotional “Top Doctor” issues, which Connolly claimed are typically top sellers in newsstands and for advertisers.

Super Doctors, based in Minnesota, employs a similar methodology of physician nominations and credential verification. Their disclaimer, however, is even more explicit about the limitations of their “Super Doctor” designation: “No representation is made that the quality of the medical services provided by the physicians listed in this Web site will be greater than that of other licensed physicians.”

Becky Kittelson, research director for Super Doctors, positioned their list as “a starting point” for patients. “We never say you should only go to this one,” she emphasized.

Super Doctors also profits from premium website listings, commemorative plaques, and advertising in publications that feature their recognized doctors.

Those glossy magazine spreads showcasing “The Best” plastic surgeons, orthopedic specialists, or other medical professionals often found in airline magazines? These are frequently advertising sections orchestrated by Madison Media Corp. of New York City. They essentially leverage the selections of companies like Castle Connolly or Super Doctors. Doctors who have received these prior accolades can then pay Madison Media to be featured in airline publications, explained John Rissi, president and owner of Madison Media.

When questioned about how he ensures the doctors featured in “The Best” ads are truly the best, Rissi admitted, “I guess in this world it’s hard to find the absolute best. It’s all through reputation and interpretation.”

Healthcare quality experts scoffed at this notion. Dr. John Santa, who previously led healthcare quality measurement initiatives at Consumer Reports, pointed out the inherent flaws in nomination-based systems. These systems, he argued, are easily manipulated by doctors with intertwined financial interests – partners within the same practice or doctors who frequently refer patients to one another. “If you examine these methodologies, they are riddled with economic and relationship biases,” Santa stated.

Santa condemned these vanity awards as an insult to patients who deserve reliable information when choosing healthcare providers. He argued that even the most reputable awards barely scratch the surface of assessing true physician quality, often only verifying basic credentials. “I’m sorry, but being in good standing with a state licensing board is a very low bar,” Santa asserted. “Being board certified is a very low bar.”

Months after my own “Top Doctor” induction, I decided to probe further into Top Doctor Awards’ selection process, this time without revealing my prior “honor.” I was directed to Donna Martin in client services, who explained that “Top Doctors” could be nominated by peers for their accomplishments. She also mentioned a “full interview process” encompassing questions about education, leadership, and awards (interestingly, no one had inquired about my journalism degree).

My interest piqued when she mentioned a research team, but further details about their methodology were deemed “proprietary.”

When I followed up with Martin, questioning the rigor of their process given my own “Top Doctor” status, she promised to review my account and call me back. I’m still awaiting that call.

Turning my attention to my fellow “Top Doctors”—the actual physicians who shared this accolade—I wondered about their perceptions of this recognition. I contacted Dr. Lewis Maharam, a sports medicine specialist in New York City known as the “Running Doc.” He expressed no surprise at being recognized by Top Doctor Awards, mentioning his extensive collection of similar accolades. “I’m sort of in that echelon or class,” he said. “If you’re finding people that don’t deserve [the awards], then maybe you’re onto something.”

It was at this point I revealed my own “Top Doctor” status.

“That’s pretty strong evidence that it’s not legitimate,” Dr. Maharam conceded, his tone shifting immediately. “It might have been that my assistant just sent in a check.”

Dr. Maharam suggested that busy doctors are easily targeted by such schemes. He admitted that inclusion in these lists, even questionable ones, can be beneficial for attracting patients. However, my story prompted him to reconsider. Moving forward, he pledged to inquire about the selection process for any similar awards and indicated he might not renew his “Top Doctor” award in 2019. I didn’t take it personally.

I attempted to contact roughly a dozen other “Top Doctors”—orthopedic and gynecologic surgeons, allergists, infectious disease specialists, even an orthodontist, spread across the country. The sheer number of recipients was staggering. While most calls went to voicemail, I did speak with some assistants who were noticeably alarmed to learn of my “Top Doctor” ranking. Dr. Maharam was the only physician who returned my call directly.

Despite the dubious nature of the award, a small smile crept across my face when my faux cherry wood and gold “Top Doctor” plaque arrived at the ProPublica newsroom. During the ordering process, the saleswoman had asked about my specialty. The entire charade was so absurd I could have claimed neurosurgery. But in the spirit of journalistic integrity, I told her the truth: “investigations.”