Sócrates, while his World Cup journey with Brazil never progressed beyond the quarter-finals, remains an unforgettable figure in the tournament’s rich history. Instantly recognizable by his distinctive curly black hair, a beard reminiscent of Che Guevara, and his commanding 6’4” stature, he embodied the image of a revolutionary both on and off the pitch. This captivating persona, combined with his exceptional football skills and intellectual depth, cemented his legacy far beyond the realm of sports.

At the 1986 World Cup in Mexico, it was the iconic headband, fashioned from a teammate’s sock, that became synonymous with Sócrates. This simple yet powerful accessory, worn as Brazil faced France in the quarter-final shootout where he unfortunately missed a crucial penalty, etched itself into the memories of millions. While later iterations of the headband displayed various slogans – ‘The People Need Justice’, ‘Yes To Love, No To Terror’, ‘No Violence’ – it was his initial message that resonated most profoundly. Following the devastating Mexico City earthquake the previous year, a tragedy that claimed thousands of lives and exposed deep societal inequalities, the host nation was in mourning. Sócrates’ headband bore a simple yet impactful message of solidarity: ‘México Sigue En Pie’—’Mexico Still Stands’.

Socrates in 1986 with 'Mexico Still Stands' headband

Socrates in 1986 with 'Mexico Still Stands' headband

Reflecting on the motivation behind this message, Sócrates later explained, ‘When we got to Mexico, the disaster caused by a terrible earthquake that had struck the country before the start of the World Cup was the trigger that made up my mind to seize the opportunity, at a time when the whole world was watching the event, and to highlight some critical points of social reality.’ His inspiration for the headband protest came from seeing a young girl on television wearing a tiara. This sparked the idea to use his own forehead as a platform to protest against ‘the absurdities that exist in humanity.’

Even before the symbolic headbands, Sócrates’ commitment to protest was evident. Prior to a group stage match against Spain, the wrong national anthem played, the Hymn to the National Flag instead of the Brazilian anthem. This error angered and distracted him, yet he acknowledged, ‘Any reactions against poverty, wars, imperialism, social injustice, endemic illiteracy and many other topics were overcome as I shook my head upon hearing the first chord, and I listened to the mistake… But it was worth the attempt. It is much better to try, I believe, than to conform.’

Doctor Socrates: The Anti-Athlete Icon

Sócrates was far from a typical footballer, even in an era when the sport was more deeply intertwined with community values. A charismatic leader and a creative force on the field, he became a romanticized hero in the public imagination for his actions beyond the game. His lifestyle choices, including smoking and drinking, defied the conventional athlete image, embodying a freewheeling nonchalance that mirrored his playing style. He famously declared himself ‘an anti-athlete.’ Adding to his unique profile, he was also a qualified medical doctor, earning him the nickname ‘Doctor Sócrates’ – a seeming contradiction that only amplified his image as a nonconformist and intellectual footballer.

Sócrates understood the power of his football talent as a platform to reach a vast audience. And what talent it was. An intelligent and composed midfielder, he was renowned for his exquisite passing ability and also for scoring spectacular goals, particularly with backheels. Pelé, the legendary three-time World Cup winner, is famously quoted as saying that Sócrates played better going backwards than most players did going forwards. The Brazilian national team he captained at the 1982 World Cup in Spain is often hailed as one of the greatest teams never to win the tournament. Their journey ended after a 3-2 defeat to eventual champions Italy in a second-round group stage match – a format quirk of that era – in a game described by his teammate Falcão as ‘one of the greatest games in the history of football.’

Socrates and Corinthians team wearing 'Vote on the 15th' shirts in 1982

Socrates and Corinthians team wearing 'Vote on the 15th' shirts in 1982

Socrates Brazil Doctor: Amplifying His Voice Beyond the Field

After retiring from professional football, with his final game for Brazil being that quarter-final loss at Mexico ’86, Sócrates reflected, ‘While I was a footballer, my legs amplified my voice.’ He dedicated himself to using this amplified voice to advocate for radical political change and to speak out against injustice both in Brazil and internationally. While his time with the Seleção brought him global recognition, his most impactful political engagement occurred during his six years playing club football for Corinthians in São Paulo. It was there that he became a central figure in the Democracia Corinthiana (‘Corinthians Democracy’) movement, directly challenging the oppressive military dictatorship that had governed Brazil since 1964.

Initially, Sócrates was not a natural dissident. Growing up in a middle-class household with a father, Raimundo, who deeply valued education – hence his son’s name after the ancient Greek philosopher – Sócrates experienced a pivotal childhood moment when he witnessed his father burning books on left-wing politics after the military coup. In an early interview in 1976, he even expressed an apolitical stance, suggesting censorship was necessary to prevent ‘things would get complicated for the government.’ However, he was an avid reader and continued his self-education, increasingly aware of Brazil’s social problems and the military regime’s harsh repression.

Upon joining Corinthians in 1978, Sócrates’ political leanings shifted leftward. He and his teammate Wladimir, later joined by Casagrande, spearheaded a movement, supported by director of football Adilson Monteiro Alves and club president Waldemar Pires, to institute direct democracy within the club. Every member of the club, from players to staff, voted on club decisions, ranging from training schedules to team travel arrangements. They also relaxed the stringent concentração tradition in Brazilian football, where players were confined to hotels before matches.

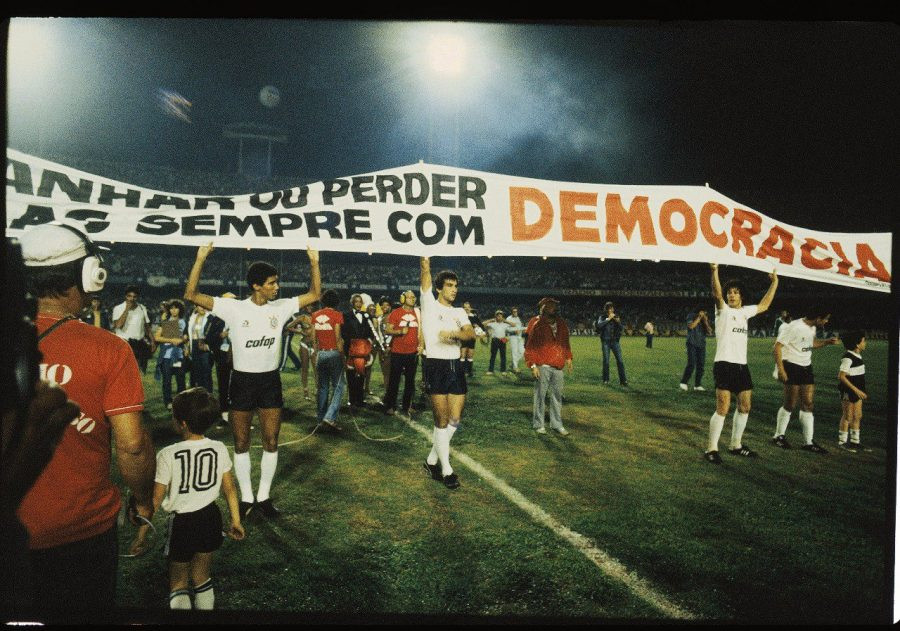

Corinthians team with 'Win or Lose, But Always with Democracy' banner in 1983

Corinthians team with 'Win or Lose, But Always with Democracy' banner in 1983

Democracia Corinthiana: Football as a Metaphor for Freedom

Challenging the authoritarian concentração was particularly symbolic, transforming Corinthians into a microcosm of Brazilian society yearning for democracy. Beyond simply adopting democratic practices within a high-profile sporting institution, Sócrates and his teammates demonstrated the effectiveness of collective action over apathy and individualism. Democracia Corinthiana brought significant success to the club, winning the Campeonato Paulista twice, in 1982 and 1983. Casagrande emphasized Sócrates’ crucial role in the movement: ‘Our movement was successful because of many points, but the most fundamental was Sócrates… We needed a genius like him, someone politicised, smart and admired. He was a shield for us. Without him, we couldn’t have Corinthians Democracy.’

The movement’s impact extended beyond the club, directly challenging the military regime. In 1982, leading up to Brazil’s first multi-party elections under military rule during the gradual ‘abertura’ (‘opening up’), Sócrates and his teammates wore shirts displaying ‘Dia 15 Vote‘ (‘Vote on the 15th’). Prior to their 1983 Campeonato Paulista victory, the team, led by Sócrates, entered the field with a large banner reading: ‘Ganhar ou Perder, Mas Sempre com Democracia‘ (‘Win or Lose, But Always with Democracy’). In the two-legged final against São Paulo, Sócrates scored twice, celebrating each goal with a raised clenched fist – a salute to the Brazilian people and their democratic aspirations.

Sócrates actively participated in the Diretas Já (‘Direct Elections Now’) movement, which mobilized millions of Brazilians – trade unionists, workers, artists, students, and many others – and played a crucial role in the transition to democracy in 1985. A defining moment in his personal story occurred when, amidst interest from Italian clubs, he stood before a massive crowd in São Paulo and pledged not to leave Brazil if a constitutional amendment for free elections was passed. Despite the amendment’s initial defeat, Sócrates, in a defiant act, moved to Fiorentina. Upon arriving in Italy, when asked about his admiration for Serie A legends Sandro Mazzola or Gianni Rivera, he famously replied, ‘I don’t know them. I’m here to read Gramsci in the original language and study the history of the labour movement.’

The Enduring Legacy of Doctor Socrates

For many Brazilians, Sócrates remains ‘an idol,’ as Rosie Siqueira of Fiel Londres, a London-based Corinthians fan club, attests. ‘He was a guy beyond his time, his views and ideals in terms of social causes and politics enlightened so many fans, not only Corinthians fans, but Brazilian fans… He was also a social cause leader, influencing players and the club staff. Sócrates was a leftist, standing against the military dictatorship we had in Brazil and defending freedom and right of speech… we don’t see that happening very often in football, be it either South American or global.’

Socrates on the pitch in Guadalajara, Mexico, 1986

Socrates on the pitch in Guadalajara, Mexico, 1986

While Democracia Corinthiana‘s impact is well-documented, the profound connection between the club’s identity and its supporters to Sócrates is often overlooked. Siqueira explains, ‘We feel very proud to be one of the only clubs with such a beautiful chapter in our history… The message behind it will always live with Corinthians now, and it keeps reminding us about our history, our origin, our purpose. Corinthians comes from poor, immigrant, working-class origins. We should never forget that. Having Democracia Corinthiana in the pages of our history book will help us keep this ideal alive.’

Sócrates passed away in 2011 at the age of 57, after battling alcoholism, on the very day Corinthians secured the Brazilian league title. He remained a vocal advocate for radical politics throughout his life, practicing medicine after football, and working as a pundit, writer, and lecturer. He supported Luiz Inácio Lula da Silva – another key figure in Diretas Já and a Corinthians fan – during Lula’s first presidential term, praising his government as ‘the best in Brazil’s history,’ while still offering critical perspectives.

In contemporary Brazil, amidst political polarization, the national team has become a symbol of division. The canary yellow shirt, once a unifying emblem, was co-opted by far-right Bolsonaro supporters. In this context, Sócrates’ legacy becomes even more relevant. Andrew Downie, journalist and author of the book Doctor Sócrates, notes, ‘With what’s going on at the moment, Sócrates is still a hugely important figure… You hear a lot of people in Brazil—especially during the election campaign when you had guys like Neymar saying they supported Bolsonaro—say things like: “How we miss a guy like Sócrates, who stood up for social causes, who stood up for human rights, who stood up for democracy and progressive positions”… he was a guy who stood up for what he thought was right.’

While some prominent Brazilian footballers endorsed Bolsonaro, others, like Sócrates’ friend Casagrande and his brother Raí, supported Lula. Raí even subtly displayed an ‘L’ for Lula while presenting the Sócrates Award at the Ballon d’Or ceremony. ‘We all know which side Sócrates would be on,’ Raí stated.

In a World Cup climate where FIFA restricts pro-equality gestures, the spirit of Sócrates’ Mexico ’86 protest is particularly poignant. For Brazilians seeking to reclaim their national team’s identity from Bolsonaro’s followers, Sócrates stands as a powerful reminder that the far right cannot monopolize national heritage. Siqueira concludes, ‘We’ve beaten Bolsonaro in this election, but that doesn’t mean Bolsonarismo is done… In my opinion, football, as usual, plays an important role in society and we will need Sócrates’ spirit alive with us.’