During the terrifying epochs of plague epidemics, particularly the Black Death that ravaged Europe in the Middle Ages, a specialized physician emerged: the plague doctor. These individuals were public health workers contracted by towns and cities to specifically care for plague victims. In a time of widespread fear and misunderstanding of disease, the plague doctor became a recognizable, if somewhat ominous, figure. Their contracts, often detailed, stipulated their duties, pay, and the populations they were obligated to serve, crucially including the poorest who could not afford private medical care.

In an age where disease was poorly understood, general physicians faced immense risk of infection, making the assignment of dedicated plague doctors a pragmatic, if desperate, measure. As many established doctors fled plague-stricken areas, the void was often filled by those with less experience, or, in some cases, individuals with no formal medical training at all. These individuals, willing to confront the epidemic head-on, stepped into roles that extended beyond medical treatment. Plague doctors were tasked with the grim responsibilities of recording plague cases and deaths, documenting last wills, conducting autopsies to better understand the disease, and meticulously keeping journals that, it was hoped, would contribute to future treatments and preventative strategies.

Amidst the chaos of the Black Death and subsequent plague outbreaks, medical understanding was rudimentary. The treatments offered by plague doctors, reflecting the medical theories of the time, were often ineffective and sometimes harmful by modern standards. Common practices included bloodletting and the draining of fluids from the characteristic buboes, the painful swellings associated with bubonic plague. Doctors also prescribed remedies intended to induce vomiting or urination, all in an attempt to rebalance the body’s humors – the ancient Greek concept of bodily fluids believed to govern health and temperament. These treatments, while grounded in the then-current medical paradigm, did little to combat the bacterial infection causing the plague.

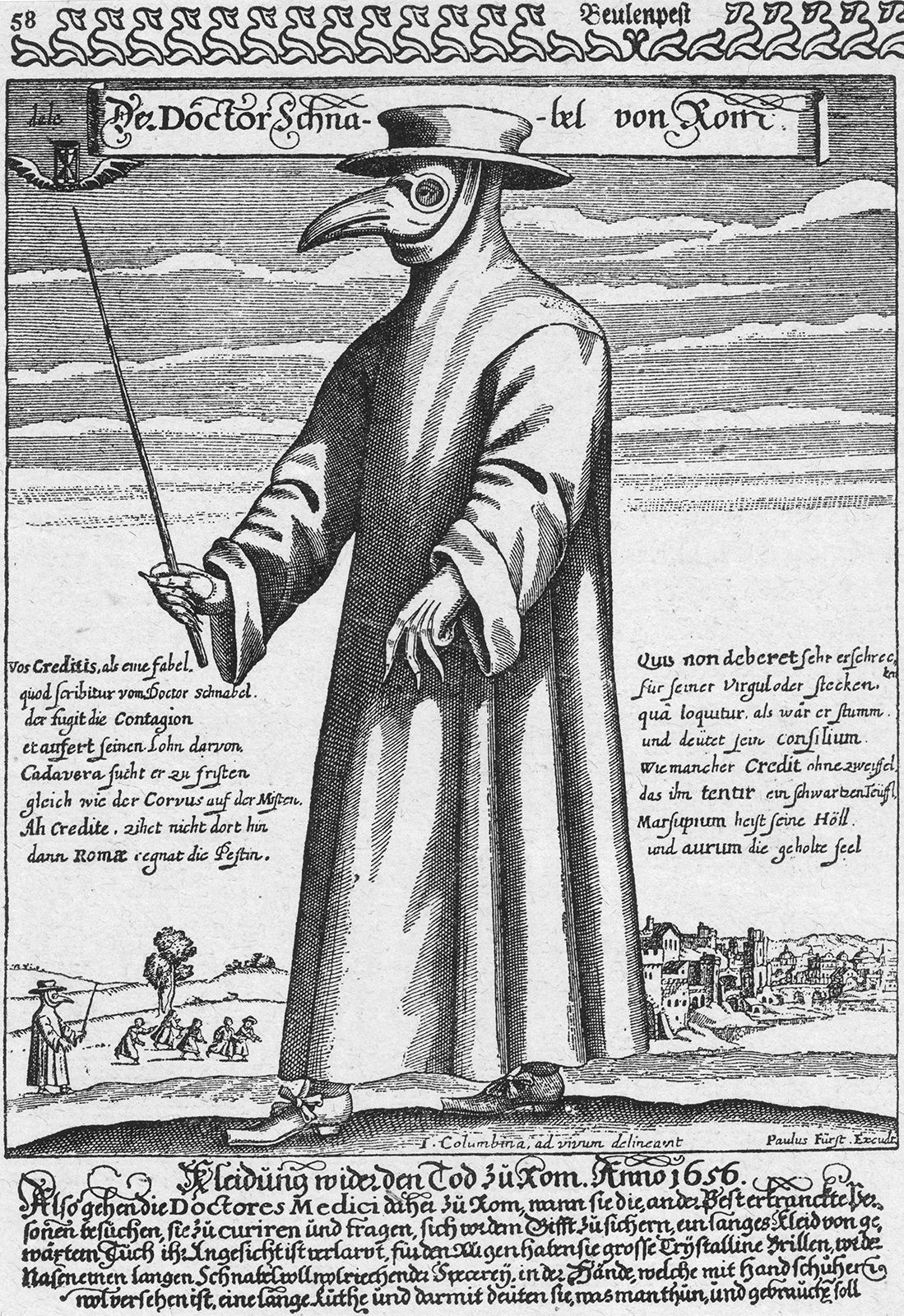

Perhaps the most enduring legacy of the plague doctor is their distinctive and unsettling attire. The iconic plague doctor costume, now synonymous with the Black Death era, featured a long, waxed coat, leggings connected to boots, gloves, and a wide-brimmed hat, all typically made of leather. The most striking element was the beaked mask, fitted with glass or crystal eyepieces to protect the eyes. Plague doctors also carried a wand or staff, used to examine patients and maintain a perceived safe distance without physical contact. While this costume is often attributed to Charles de Lorme, a 17th-century French physician, it’s important to note that earlier plague doctors did not have a standardized uniform. This macabre ensemble, initially intended as protective gear, soon became a symbol of death itself, lending itself to dark humor and caricature. The plague doctor mask and costume became a popular feature of Venetian Carnival celebrations and a stock character in Italian commedia dell’arte. Intriguingly, the plague doctor’s image has seen a modern resurgence, particularly during the COVID-19 pandemic, embraced by costume enthusiasts and as a chilling reminder of historical pandemics.

The long beak of the plague doctor mask was not merely for dramatic effect. It served a purpose rooted in the miasma theory of disease, the prevailing belief that illnesses were spread by foul-smelling air. To combat this perceived threat, the beak was packed with aromatic herbs and flowers like lavender and mint, or substances such as myrrh, camphor, and vinegar-soaked sponges. Some doctors even used theriac, a complex cure-all concoction dating back to the 1st century CE. While the miasma theory was incorrect, and the beak’s contents did not prevent plague, the costume itself, with its layers of fabric and separation from the environment, likely offered a degree of protection against infected fleas, bodily fluids, and respiratory droplets, inadvertently providing some level of barrier against the disease’s spread.