Did Doctors Prescribe Cigarettes? It may seem bizarre today, but thebootdoctor.net reveals a time when physicians were featured in cigarette ads, implying safety. Understanding this historical period sheds light on the evolution of medical knowledge and advertising ethics. Discover how views on smoking have shifted drastically over time.

Table of Contents

- Early Medical Claims

- Tobacco Industry Courts Doctors

- RJ Reynolds’s Medical Relations Division

- The “More Doctors” Campaign

- Medical Authority and Tobacco

- The Disappearing Doctor

- FAQ Section

1. What Were the Early Medical Claims in Cigarette Advertisements?

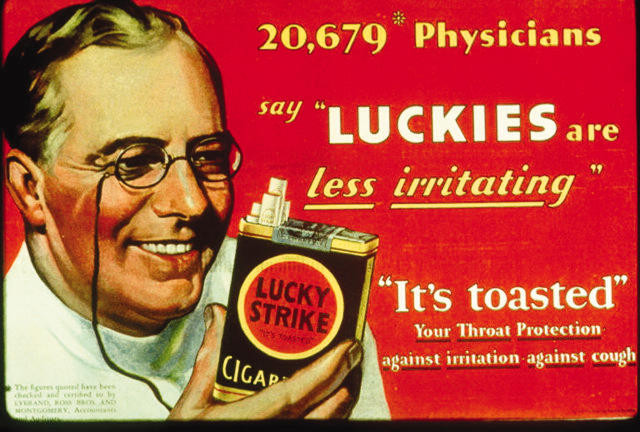

Early medical claims in cigarette advertisements focused on the idea that certain brands were “less irritating” to the throat, with some ads even claiming that doctors recommended these brands. American Tobacco was the first to feature physicians in advertisements, asserting their “toasting” process made Lucky Strikes less irritating. According to a 1930 advertisement, “20,679 Physicians say ‘LUCKIES are less irritating’,” though the evidence backing this was unsubstantiated.

These campaigns were designed to reassure the public that their brands had competitive health advantages. This tactic became increasingly important as the health effects of smoking became more apparent. One aspect of these promotional strategies was to refer directly to physicians in both images and words. Let’s explore how physicians were depicted in these advertisements and how the ad campaigns developed as health evidence implicating cigarette smoking accumulated by the early 1950s.

FIGURE 1—

FIGURE 1—

1.1 How Did Lucky Strikes Use Medical Claims in Their Advertising?

Lucky Strikes used medical claims to suggest their “toasting” process reduced throat irritation, prominently featuring doctors in their ads. American Tobacco insisted that the “toasting” process that Lucky Strikes tobacco underwent decreased throat irritation. Despite the lack of real scientific evidence, a 1930 advertisement stated that “20,679 Physicians say ‘LUCKIES are less irritating’,” featuring a reassuring doctor.

1.2 What Role Did Philip Morris Play in Early Cigarette Advertising?

Philip Morris took health claims a step further by directly referencing research conducted by physicians, claiming their cigarettes were “proven” to be less irritating. In a 1937 advertisement, it was announced that according to “a report on the findings of a group of doctors . . . when smokers changed to Philip Morris, every case of irritation cleared completely and definitely improved.” This campaign contributed to making Philip Morris a major brand for the first time.

FIGURE 2—

FIGURE 2—

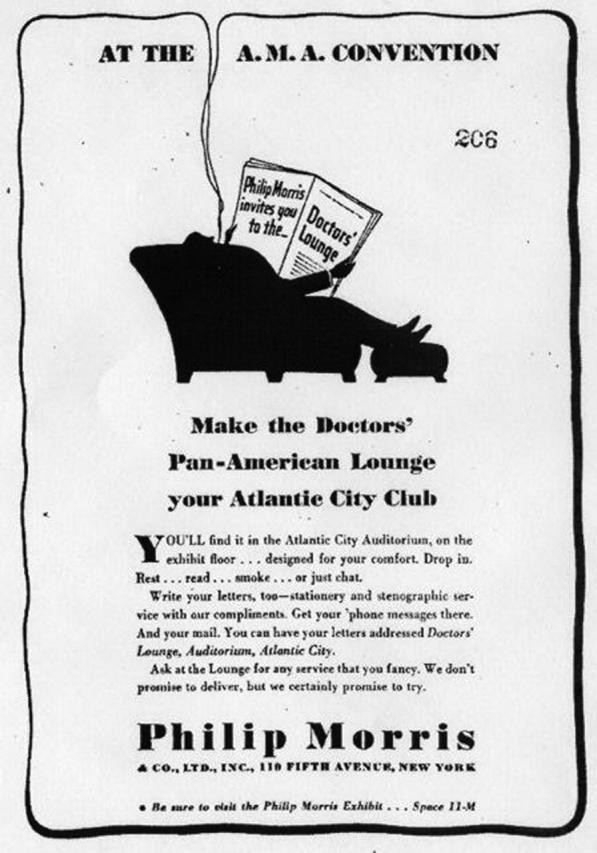

1.3 How Did Philip Morris Influence Doctors to Support Their Claims?

Philip Morris influenced doctors by sponsoring research and providing free cigarettes and reprints of scientific articles at medical conventions. As a 1936 Fortune Magazine profile of Philip Morris & Company made clear:

The object of all this propaganda is not only to make doctors smoke Philip Morris cigarettes, thus setting an example for impressionable patients, but also to implant the findings of Mulinos so strongly in the medical mind that the doctors will actually advise their coughing, rheumy, and fur-tongued patients to switch to Philip Morris on the ground that they are less irritating.

2. How Did the Tobacco Industry Actively Court Doctors?

The tobacco industry actively courted doctors by placing advertisements in medical journals, sponsoring medical events, and even creating specialized medical relations divisions. For tobacco companies, physicians’ approval of their product could prove to be essential, especially since patients often brought smoking-related symptoms and health concerns to the attention of their doctors. Through advertisements appearing in the pages of medical journals for the first time in the 1930s, tobacco companies worked to develop close, mutually beneficial relationships with physicians and their professional organizations.

2.1 Why Was Physician Approval Important to Tobacco Companies?

Physician approval was crucial because patients often sought medical advice for smoking-related symptoms, making doctors key influencers. During this era, there was a strong tendency to avoid altogether causal hypotheses in matters so clearly complex. There was—and would remain—a powerful notion that risk is largely variable and thus, most appropriately evaluated and monitored at the individual, clinical level.

2.2 How Did Tobacco Companies Use Medical Journals in Their Advertising Strategy?

Tobacco companies used medical journals to promote their products, which provided income for the journals while also appealing to doctors’ expertise. Philip Morris praised physicians in these advertisements with taglines like “Every doctor is a doubter” and “Doctor as judge” as they appealed to physicians’ expert ability to evaluate the evidence, referring them to scientific articles that they claimed illustrated the superiority of their brand.

2.3 What Types of Taglines Were Used to Appeal to Physicians?

Taglines such as “Every doctor is a doubter” and “Doctor as judge” were used to appeal to physicians’ sense of expertise and ability to evaluate evidence. As one such advertisement explained in its entirety in 1939, “If you advise patients on smoking—and what doctor does not—you will find highly important data in the studies listed below. May we send you a set of reprints?” Physicians became, through this process, an increasingly important conduit in the marketing process.

3. What Was the Role of RJ Reynolds’s Medical Relations Division?

The Medical Relations Division (MRD) of RJ Reynolds focused on promoting Camels by courting researchers to substantiate health claims, and directly soliciting doctors through various advertisements. RJ Reynolds created a Medical Relations Division (MRD) in the early 1940s that became the base of their aggressive physician/health claims promotional strategy. They directly solicited doctors in a 1942 advertisement that appeared in medical journals describing the MRD. Declaring that “[t]he most significant medical data is derived from the every-day records of practising [sic] physicians,” the text asserted “your office record reports in such cases should prove interesting to study.”

3.1 How Did RJ Reynolds Target Doctors Through Their Medical Relations Division?

RJ Reynolds targeted doctors by directly soliciting them for information and promoting research that supported their claims, even if it lacked substantial scientific backing. In the late 1930s and early 1940s, Clarke—who had no medical or scientific training—corresponded with many researchers who were pursuing questions relating to smoking and health. The MRD financed research that Reynolds then referred to in advertisements.

3.2 What Claims Did RJ Reynolds Make About Camels Cigarettes?

RJ Reynolds claimed that Camels were the slowest burning cigarettes, which supposedly reduced nicotine absorption, making them a safer option. Rather than emphasizing claims of moistness as Philip Morris had done, RJ Reynolds focused on nicotine absorption, insisting that Camels were the slowest burning of all cigarettes. Camels’ slow burning rate, their advertisements now asserted, decreased nicotine absorption; as a result, Camels offered smokers an advantage over other, faster-burning brands.

3.3 How Did RJ Reynolds Engage with Medical Conventions?

RJ Reynolds actively participated in medical conventions, offering free cigarettes and exhibits that showcased their research, linking clinical medicine to investigative science. For example, social commentator Bernard Devoto described the exhibit hall of the 1947 American Medical Association (AMA) convention in Atlantic City, where doctors “lined up by the hundred” to receive free cigarettes.

FIGURE 3—

FIGURE 3—

4. What Was the “More Doctors” Campaign and How Did It Evolve?

The “More Doctors” campaign was a series of advertisements by RJ Reynolds that prominently featured doctors, initially claiming that “More doctors smoke Camels than any other cigarette.” When the “More Doctors” campaign began in January 1946, it also focused on the respected and romantic image the medical profession had achieved in American society. Featuring 6 illustrations of physicians with patients—in the laboratory or sitting back with cigarette in hand—this first advertisement personalized the physician for the readers of such popular magazines as Ladies’ Home Journal and Time.

4.1 How Did RJ Reynolds Initially Present the “More Doctors” Claim?

RJ Reynolds initially claimed that surveys showed more doctors smoked Camels than any other cigarette, linking this to the consumer’s own doctor to create immediacy. Prefaced with the bold statement that “Every doctor in private practice was asked:—family physicians, surgeons, specialists . . . doctors in every branch of medicine,” the advertisement touted the thoroughness of their survey and insisted that “yes, your doctor was asked . . . along with thousands and thousands of other doctors from Maine to California.”

4.2 How Did the “More Doctors” Campaign Adapt Over Time?

The campaign adapted by toning down the claim to “113,597 physicians” surveyed, avoiding direct implications that doctors recommended smoking Camels for health reasons. With the Federal Trade Commission already challenging suspected health claims in cigarette advertisements, RJ Reynolds toned down their copy, quickly shifting their claim to “113,597 physicians” surveyed rather than all physicians.

4.3 How Did the Campaign Idealize Physicians?

The campaign idealized physicians by portraying them as dedicated, trustworthy, and vital members of the community, often linking them to wartime patriotism and medical science advancements. As a 1944 advertisement that appeared in Life Magazine entitled “Doctor of Medicine . . . and Morale” illustrated, doctors on the front received hero status:

He wears the same uniform. . . . He shares the same risks as the man with the gun. . . . Yes, the medical man in the service today is a fighting man through and through, except he fights without a gun. . . . [H]e’s a trusted friend to every fighting man. . . .[H]e well knows the comfort and cheer there is in a few moments’ relaxation with a good cigarette . . . like Camel . . . the favorite cigarette with men in all the services.

FIGURE 4—

FIGURE 4—

5. How Did Medical Authority Influence Tobacco Advertising?

Medical authority heavily influenced tobacco advertising by lending credibility to claims and reassuring consumers about the safety of smoking. After the initial onslaught of heroic physicians and medical miracles in 1946, the “More Doctors” advertisements in 1947 and 1948 continued to remind readers about the survey as the focus of the advertisements shifted. The main slogan of one such campaign was “Experience is the best teacher.”

5.1 How Did Tobacco Companies Use Physicians to Validate Their Claims?

Tobacco companies used physicians to validate their claims by featuring them in advertisements, citing their “scientific investigations,” and emphasizing individual clinical judgment. In July 1949 issues of both local and national medical journals, RJ Reynolds asked, “How mild can a cigarette be?” In answering this question, the advertisement juxtaposed a “doctors report”—illustrated with a physician, cigarette in hand and head mirror strapped around his brow—with a “smokers report”—illustrated with a smiling “Sylvia MacNeill, secretary.”

5.2 What Themes Were Common in Tobacco Advertisements Featuring Physicians?

Common themes included throat irritation, mildness, and individual experience, with advertisements encouraging smokers to judge the safety of cigarettes for themselves. The question of throat irritation so central to many 1920s and 1930s ad campaigns again emerged here as RJ Reynolds introduced a “mildness” theme. With the central claim that Camels did not irritate the throat, Reynolds featured both the physician-researcher and the everyday smoker to convince readers of Camels’ mildness.

5.3 How Did Tobacco Companies Attempt to Subvert Emerging Health Findings?

Tobacco companies attempted to subvert emerging health findings by emphasizing individual judgment and promoting the idea that smokers could determine the safety of cigarettes on their own. These advertisements worked to subvert the emerging population-based epidemiological findings by emphasizing the primacy of “individual” judgment.

Figure 5—

Figure 5—

6. When Did the Use of Doctors in Tobacco Advertising Decline?

The use of doctors in tobacco advertising declined sharply in the mid-1950s as scientific evidence linking smoking to lung cancer became more widely known and accepted. Ultimately, however, the use of physicians in Camel advertisements could not be sustained as the health evidence against cigarettes accumulated. When disturbing scientific results connecting lung cancer and cigarettes began to emerge, Camel advertisements shifted away from physicians’ judgment and authority.

6.1 What Scientific Discoveries Influenced the Decline?

Key scientific discoveries, such as the work of Evarts Graham, Ernst Wynder, A. Bradford Hill, and Richard Doll, linking smoking to lung cancer, significantly influenced the decline. By 1953, when Wynder, Graham, and their colleague Adele Croninger published laboratory findings confirming that cigarettes were carcinogenic, scientific findings constituted a critical threat to the industry. Tobacco executives were well aware both of these findings and of the public attention they were receiving, and their statements and actions reflected an understanding that this new scientific evidence constituted a full-scale crisis for their corporations.

6.2 How Did the Tobacco Industry Respond to Growing Concerns?

The tobacco industry responded by jointly agreeing to stop making health claims in their advertising and shifting to promoting filter cigarettes as a safer alternative. In December 1953, the tobacco executives met to devise a joint strategy. They hired prominent public relations firm Hill & Knowlton to aid in this effort. As a planning memo makes clear, health claims were considered to be no longer viable.

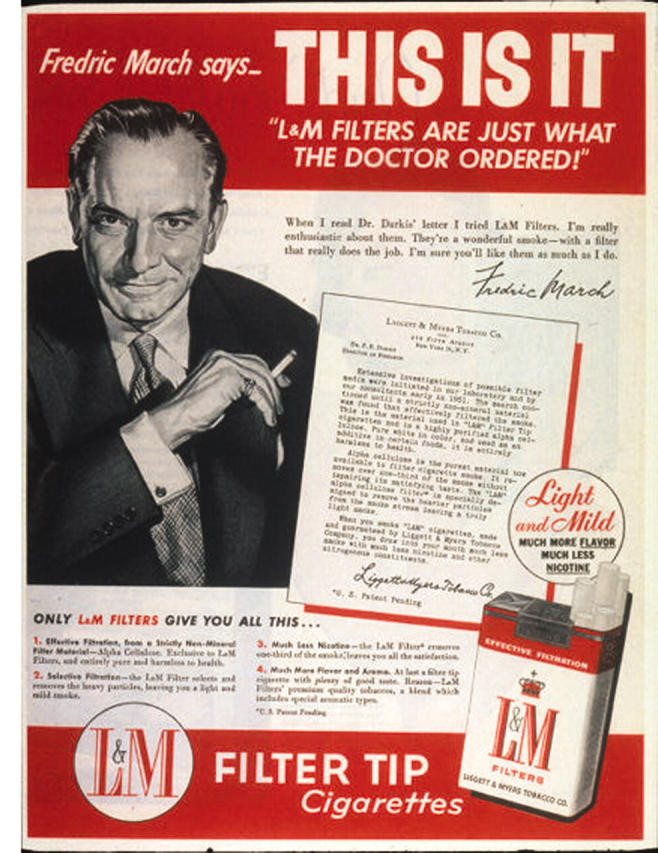

6.3 What Was the Last Notable Reference to Doctors in Cigarette Advertising?

The last notable reference was in 1954 when Liggett and Myers claimed their L&M filter cigarette was “Just what the doctor ordered!”, although this was later revealed to be a research chemist, not a medical doctor. In a typical advertisement that appeared in a February issue of Life magazine, Hollywood star Fredric March made this assertion after having read the letter written by a “Dr Darkis” that was inset into the advertisement. More significantly, this use of implicit doctor endorsement of cigarettes would not occur again in American advertising after this campaign.

FIGURE 6—

FIGURE 6—

6.4 How Did the AMA React to Cigarette Advertising?

In 1953, the AMA decided to stop accepting cigarette advertisements in its publications and banned cigarette companies from exhibiting their products at AMA conventions. After conducting its own survey of physicians, the AMA explained in a letter to tobacco companies that “a large percentage of physicians interviewed expressed their disapproval” of cigarette advertisements in medical journals. With the AMA publicly condemning the Kent ad campaign in 1954 as “hucksterism,” it became even more clear to tobacco companies that the purported allegiance with physicians was no longer feasible or effective.

7. FAQ Section

7.1 Did doctors really prescribe cigarettes in the past?

While doctors didn’t “prescribe” cigarettes in the modern sense, they were often featured in advertisements endorsing specific brands, implying that these cigarettes were safe or even beneficial.

7.2 Why were doctors featured in cigarette advertisements?

Doctors were seen as trusted figures in society, so their endorsement of a product was considered a powerful marketing tool.

7.3 Which cigarette brands used doctors in their advertising?

Several brands, including Lucky Strike, Philip Morris, and Camel, used doctors in their advertising campaigns.

7.4 What types of claims did these advertisements make?

Advertisements claimed that certain cigarettes were “less irritating,” “milder,” or even beneficial for throat health.

7.5 How did the public react to these advertisements?

Initially, the public largely accepted these advertisements due to the high regard for medical professionals.

7.6 What changed that led to the decline of these advertisements?

Mounting scientific evidence linking smoking to severe health problems, such as lung cancer, led to the decline.

7.7 When did medical journals stop accepting cigarette advertisements?

The Journal of the American Medical Association (JAMA) stopped accepting cigarette advertisements in 1953.

7.8 What are the ethical implications of these advertisements?

These advertisements raised serious ethical concerns about the manipulation of public trust in medical professionals for commercial gain.

7.9 How has our understanding of smoking and health evolved since then?

Our understanding has drastically evolved, with overwhelming evidence confirming the harmful effects of smoking on nearly every organ in the body.

7.10 Where can I find more reliable information about foot health?

For reliable and expert information on foot health, visit thebootdoctor.net.

Understanding the historical context of doctors in cigarette advertisements is crucial for appreciating the progress in medical ethics and public health awareness. Today, healthcare professionals are committed to evidence-based practices and transparent communication, ensuring that public health remains the top priority. If you are in Houston, TX and looking for reliable and specialized foot care, visit us at 6565 Fannin St, Houston, TX 77030, United States. You can also call us at +1 (713) 791-1414 or explore our services online at thebootdoctor.net.

Don’t wait any longer to take control of your foot health. Explore the valuable resources available at thebootdoctor.net and take the first step towards healthier, happier feet.