During periods of widespread disease like the bubonic plague, specialized figures known as plague doctors emerged. These weren’t necessarily the most skilled physicians of their time; rather, they were individuals specifically contracted by cities and towns to manage and treat plague victims. Their presence, particularly during the European epidemics of the Middle Ages, is a stark reminder of humanity’s historical battles against devastating illnesses. These doctors, while often ineffective in treatment by modern standards, played a crucial role in communities ravaged by the plague.

Plague doctors were essentially public health officials hired during outbreaks. Cities employed them when the plague struck, as general practitioners were understandably hesitant to expose themselves to the highly contagious disease. Many established doctors fled affected areas, leaving a void that needed to be filled. This situation led to a diverse range of individuals becoming plague doctors. Some were indeed trained physicians, perhaps younger doctors or those struggling to establish themselves. However, others had minimal to no medical training. In desperate times, willingness to confront the disease often outweighed formal qualifications. Their contracts, funded by the city, stipulated they treat everyone, even the poorest who couldn’t afford care, and to venture into the most afflicted neighborhoods.

Beyond attempting to treat the sick, plague doctors had numerous administrative and social duties. Accurately recording the number of plague cases and deaths was vital for tracking the epidemic’s progression. They were also called upon to witness wills of the dying, ensuring legal and familial matters were settled amidst the chaos. In some instances, plague doctors even performed autopsies, rudimentary as they may have been, in a desperate attempt to understand the disease. Many diligently kept journals and casebooks, documenting symptoms, treatments, and observations. These records, while not immediately leading to breakthroughs, contributed to the slow accumulation of medical knowledge over time.

The treatments administered by plague doctors were rooted in the medical understanding of the Middle Ages, which was limited and often misguided. The prevailing theory revolved around the concept of humorism – the belief that bodily health depended on the balance of four fluids or humors. Treatments aimed to restore this balance, often through methods we now recognize as ineffective or even harmful. Bloodletting, or draining blood, and purging, inducing vomiting or urination, were common practices intended to expel the supposed imbalance. Buboes, the characteristic swollen lymph nodes of bubonic plague, were sometimes lanced and drained. Herbal remedies and various concoctions were also prescribed, but their efficacy against the plague was negligible.

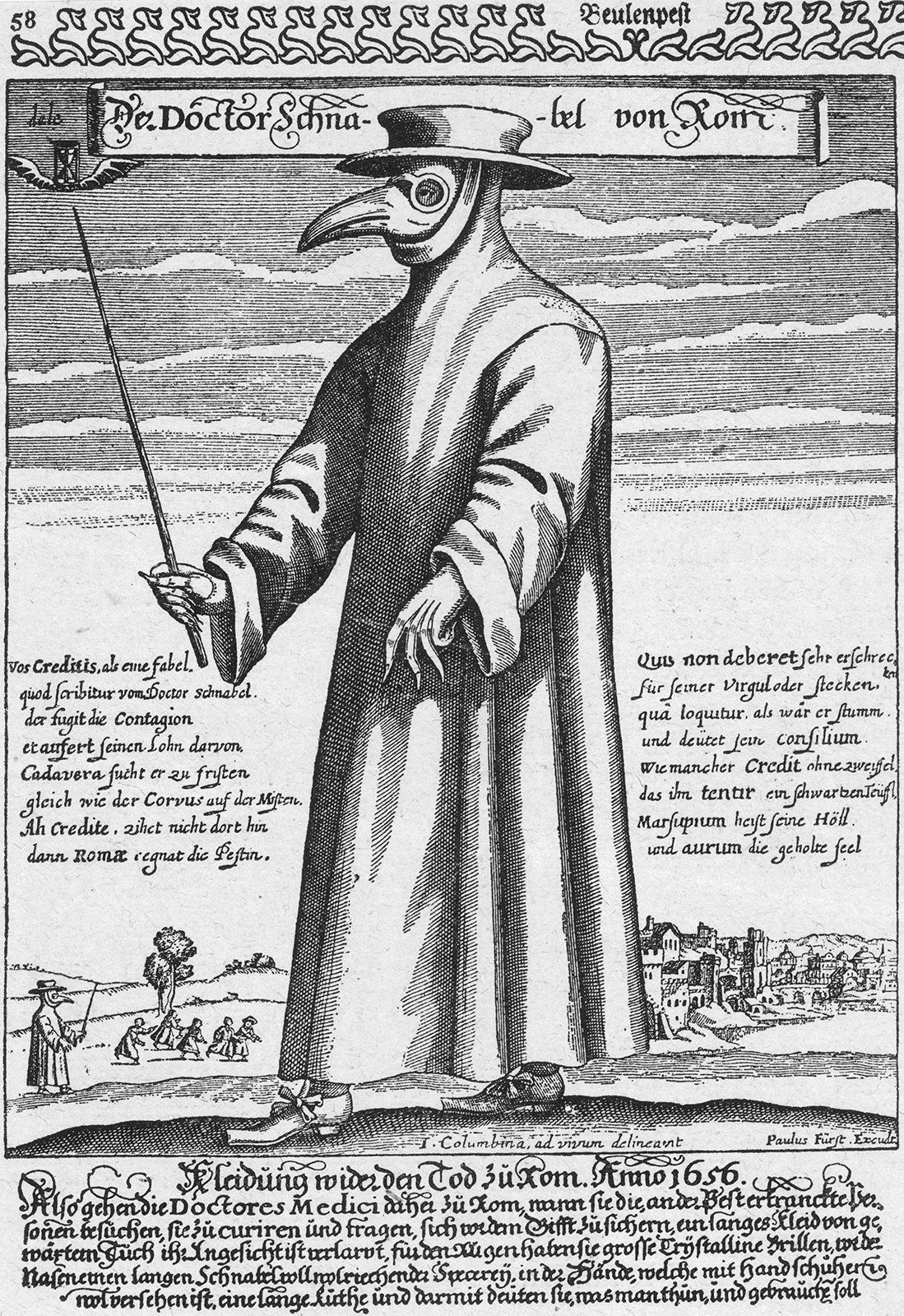

Perhaps the most enduring image of the plague doctor is their distinctive and somewhat unsettling attire. This iconic costume, featuring a long, waxed coat, leggings connected to boots, gloves, a wide-brimmed hat, and most notably, a beaked mask, is strongly associated with these figures. While earlier plague doctors didn’t have a standardized uniform, this particular ensemble is largely attributed to Charles de Lorme, a 17th-century French physician. Constructed primarily of leather, the costume was designed to create a barrier against disease. The mask incorporated glass or crystal eyepieces for eye protection. Plague doctors also carried a wand or staff, allowing them to examine patients and maintain a perceived safe distance without physical contact.

The beaked mask, the costume’s most striking feature, was not merely for dramatic effect. It served a specific purpose based on the miasma theory of disease. This theory posited that diseases were spread through foul-smelling air, or “miasma.” To combat this, the beak of the mask was filled with aromatic substances. Fragrant herbs and flowers like lavender and mint, along with materials like myrrh, camphor, and vinegar-soaked sponges, were packed into the beak. The intention was to filter and purify the air the doctor breathed, protecting them from the noxious miasma believed to cause the plague. Ironically, while the miasma theory was incorrect, the costume, in practice, likely offered some degree of protection. The layers of fabric and the mask could have reduced exposure to infected fleas and respiratory droplets, offering a limited barrier against transmission, albeit unintentionally.

The image of the plague doctor, once a symbol of fear and death, has transformed over time. The macabre appearance of the beaked figure lent itself to dark humor and caricature. Plague doctors became stock characters in commedia dell’arte and popular figures in Venetian Carnival, their costumes repurposed for festive and theatrical contexts. In a more recent twist, the plague doctor image has experienced a resurgence in popular culture, particularly during the COVID-19 pandemic. The costume has been adopted by costume enthusiasts and become a recognizable symbol in contemporary media, reflecting a renewed, albeit sometimes ironic, interest in historical responses to pandemics and the figures who navigated them. The doctors of the bubonic plague, with their eerie masks and limited medical tools, remain a fascinating and somewhat unsettling chapter in medical history, embodying both the fear and the resilience of societies facing devastating epidemics.