about-edward-jenner.jfif

about-edward-jenner.jfif

Edward Jenner, a name synonymous with the eradication of smallpox, was born on May 17, 1749, in Berkeley, Gloucestershire, England. As the eighth of nine children born to Reverend Stephen Jenner, the vicar of Berkeley, and his wife Sarah, his early life was steeped in the quietude of rural England, yet destined for a profound impact on global health. His journey from a country upbringing to becoming a medical pioneer is a testament to observation, perseverance, and a revolutionary idea that would save countless lives.

Education and Formative Medical Years

Jenner’s formal education began in Wotton-under-Edge and continued in Cirencester. A significant event during his schooling was his inoculation against smallpox, a common practice at the time known as variolation. This early experience with smallpox inoculation, while intended to protect, had lasting effects on his health and likely contributed to his later quest for a safer alternative. At the age of fourteen, Jenner embarked on his medical apprenticeship, a seven-year commitment under Mr. Daniel Ludlow, a surgeon in Chipping Sodbury. This period was crucial for developing practical surgical skills and gaining hands-on experience, forming the bedrock of his medical expertise.

In 1770, seeking advanced medical training, Edward Jenner moved to London and joined St. George’s Hospital. This pivotal move placed him under the tutelage of the esteemed surgeon and experimentalist, John Hunter. Hunter, a prominent figure in 18th-century surgery and science, quickly recognized Jenner’s exceptional aptitude for dissection, keen investigative mind, and comprehensive understanding of both plant and animal anatomy. Their professional association blossomed into a lifelong friendship and intellectual correspondence, profoundly influencing Jenner’s scientific approach and career trajectory. After completing his rigorous training in 1772 at the age of 23, Dr. Edward Jenner returned to his roots in Berkeley. He established himself as the local physician and surgeon, becoming a fixture in the community. While later in life, professional opportunities led him to set up practices in London and Cheltenham, Jenner’s heart and home remained firmly rooted in Berkeley for the remainder of his life.

The Intrigue of Cowpox

Like all doctors of his era, Edward Jenner, the dedicated physician, routinely performed variolation. This was the accepted method to confer immunity to smallpox, despite its inherent risks. However, from the nascent stages of his medical career, Dr. Jenner was captivated by local folklore. Country wisdom held that individuals who contracted cowpox, a disease they caught from their cows, were subsequently immune to the more deadly smallpox. This rural belief, combined with his own unsettling experience with variolation as a child and the acknowledged dangers of the procedure, ignited a spark of inquiry that would lead to his groundbreaking research.

Cowpox is a mild viral infection that primarily affects cows. It manifests as weeping sores, or pocks, on the udders of cows, causing minimal discomfort to the animals. Milkmaids, in close contact with cows, occasionally contracted cowpox. While they might experience a few days of feeling unwell and develop a limited number of pocks, typically on their hands, the disease was generally benign and short-lived. This stark contrast to the severity of smallpox was the crucial observation that fueled Dr. Jenner’s revolutionary idea.

CowpoxJennerMuseumPic.JPG

CowpoxJennerMuseumPic.JPG

Alt text: Close-up of cowpox lesions on a cow’s udder, a milder disease that held the key to preventing deadly smallpox, as discovered by Dr. Edward Jenner.

The Seminal First Vaccination

May 1796 marked a turning point in medical history. Sarah Nelmes, a dairymaid, sought Dr. Edward Jenner’s medical opinion regarding a rash on her hand. Jenner diagnosed her condition as cowpox, not smallpox. Sarah confirmed that Blossom, one of her Gloucester cows, had recently been afflicted with cowpox. For Dr. Jenner, this was the opportune moment to rigorously test the long-held theory about cowpox’s protective properties against smallpox. He decided to conduct an experiment, using matter from Sarah Nelmes’ cowpox lesion to inoculate someone who had never had smallpox.

James Phipps, the eight-year-old son of Jenner’s gardener, became the subject of this pivotal experiment. On May 14th, Dr. Jenner made a few superficial scratches on James’ arm and introduced matter taken directly from a cowpox pock on Sarah Nelmes’ hand into these scratches. Days later, James developed a mild case of cowpox, experiencing a slight illness, but he fully recovered within a week. This confirmed to Jenner that cowpox could be transmitted from cows to humans and from person to person. The critical next step was to ascertain whether this cowpox infection would indeed protect James from smallpox. On July 1st, Dr. Jenner performed variolation on James, deliberately exposing him to smallpox. To Jenner’s immense relief and as he had hypothesized, James showed no signs of developing smallpox, neither on this occasion nor in subsequent tests to challenge his immunity. This successful experiment was the first documented instance of vaccination, a term that would later be derived from ‘vacca,’ the Latin word for cow, in honor of Jenner’s discovery.

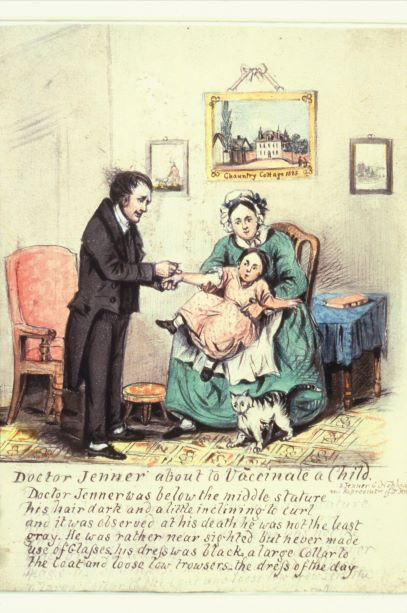

CollectionJennervaccinatingJennerMuseum.jpg

CollectionJennervaccinatingJennerMuseum.jpg

Alt text: Historical artwork depicting Dr. Edward Jenner vaccinating a patient, illustrating the groundbreaking medical procedure he pioneered to combat smallpox.

Publication and Dissemination of Findings

Dr. Jenner meticulously continued his research, conducting numerous experiments to validate his initial findings. In 1798, he compiled his comprehensive research into a seminal publication: ‘An Inquiry into the Causes and Effects of the Variolae Vaccinae; a Disease Discovered in some of the Western Counties of England, Particularly Gloucestershire, and Known by the Name of The Cow Pox’. This groundbreaking work detailed his experiments and laid out the scientific basis for vaccination. In each of the following two years, Dr. Edward Jenner published further experimental results, each reinforcing his original theory: cowpox inoculation effectively conferred protection against the devastating smallpox disease.

DrJennersHouseMuseum_Gardens11MuseumPic.jpg

DrJennersHouseMuseum_Gardens11MuseumPic.jpg

Alt text: Exterior view of Dr. Edward Jenner’s house and museum in Berkeley, Gloucestershire, UK, the home and workplace of the pioneering doctor.

Resistance from the Medical Community

Despite the compelling evidence presented by Dr. Jenner, his innovative vaccination technique did not immediately gain universal acceptance within the medical profession. One significant obstacle was practical. Cowpox was not widespread, making it difficult for physicians to obtain the necessary cowpox matter to replicate Jenner’s process. Doctors who wished to implement vaccination often had to rely on samples from Dr. Jenner himself. In an era preceding the understanding of germ theory, cowpox samples were frequently contaminated with smallpox due to the practices of those handling them, who often worked in smallpox hospitals or performed variolation. This contamination led to misleading claims that cowpox vaccination was no safer than traditional smallpox inoculation. Furthermore, a segment of the surgical community actively resisted Jenner’s success. Variolators, who derived substantial income from performing smallpox inoculations, perceived Jenner’s safer and more effective cowpox treatment as a direct threat to their livelihoods. This economic factor contributed to the initial resistance to vaccination.

The Anti-Vaccination Movement

Beyond professional skepticism, public apprehension also arose. People harbored fears about the implications of introducing material originating from cows into their bodies. Religious objections surfaced, with some arguing against being treated with substances from animals considered “lower” creatures. Despite this initial resistance, the scientific evidence in favor of vaccination became undeniable. The British Parliament eventually prohibited variolation by an Act in 1840. Subsequently, in 1853, vaccination with cowpox was mandated by law. Ironically, this compulsory vaccination led to a new wave of opposition. Protest marches and vehement public outcry erupted from those who championed freedom of choice in medical treatments, marking the early emergence of an anti-vaccination movement.

Global Spread of Vaccination

Dr. Edward Jenner dedicated a significant portion of his later life to promoting and facilitating the global adoption of vaccination. He tirelessly supplied cowpox matter to individuals and institutions worldwide and engaged in extensive correspondence on related scientific matters. His deep commitment to combating smallpox through vaccination was evident in his self-description as ‘the Vaccine Clerk to the World.’ To facilitate wider distribution of the vaccine, he developed innovative techniques for preserving and transporting cowpox matter. This included methods for drying the matter onto threads or glass, enabling it to be shipped across long distances without losing its efficacy. In recognition of his monumental contribution to public health and as compensation for the significant time he devoted away from his private practice, the British Government bestowed upon Dr. Jenner substantial financial awards: £10,000 in 1802 and a further £20,000 in 1807.

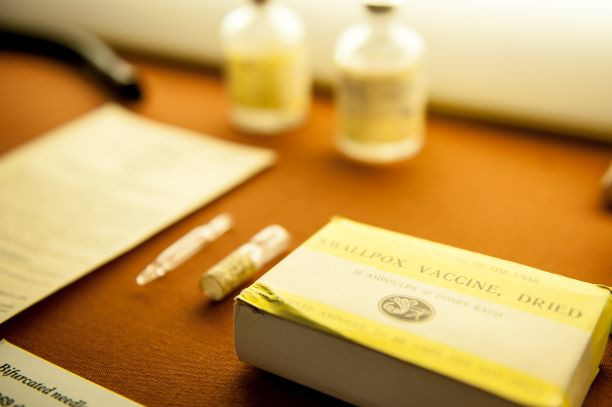

SmallPoxVaccineMuseumPic2.jpg

SmallPoxVaccineMuseumPic2.jpg

Alt text: A display of historical smallpox vaccination tools and artifacts, showcasing the instruments used to implement Dr. Jenner’s life-saving technique.

Enduring Recognition and Legacy

In honor of Edward Jenner’s transformative discovery, the technique of introducing material under the skin to confer disease protection became universally known as vaccination. This term, derived from ‘vacca,’ the Latin word for cow, immortalized Jenner’s pivotal role. He received widespread accolades and honors from cities and learned societies across the globe. He was granted the Freedom of numerous cities, including London, Glasgow, Edinburgh, and Dublin. Prestigious societies and universities worldwide conferred honorary degrees and memberships upon him. Notable tributes included a special medal minted by Napoleon in 1804, a gift of a ring from the Empress of Russia, and a string and belt of Wampum beads along with a certificate of gratitude from North American Indian Chiefs. Statues commemorating Dr. Jenner were erected in locations as distant as Tokyo and London, with the London statue eventually finding its place in Kensington Gardens after initially standing in Trafalgar Square.

The Triumph Over Smallpox

In 1967, the World Health Organization (WHO) launched a global campaign with the ambitious goal of eradicating smallpox worldwide. At that time, estimates indicated that smallpox still afflicted up to 15 million people annually. The regions most severely impacted were South America, Africa, and the Indian subcontinent. The WHO’s strategy centered on mass vaccination, aiming to immunize every individual in at-risk areas. Dedicated teams of vaccinators from across the globe traveled to even the most remote communities to administer the vaccine pioneered by Dr. Jenner.

Following an intensive surveillance period to monitor for new cases, in 1980, the WHO formally declared: “Smallpox is Dead!” This momentous announcement marked the eradication of what was once the most feared disease in human history, fulfilling a prediction made by Edward Jenner himself in 1801. It is estimated that the work initiated by Dr. Edward Jenner has resulted in saving more human lives than the contributions of any other single individual. Today, the last remaining samples of the smallpox virus are secured in just two high-security laboratories, one in Siberia and one in the United States. These samples are strictly reserved for research purposes and are protected with security measures exceeding those for nuclear weapons. The eventual plan is to destroy these remaining samples, marking the complete and irreversible eradication of smallpox, the first major infectious disease to be entirely wiped from the face of the Earth, thanks to the pioneering work of Edward Jenner, the doctor who changed the world.