During the terrifying epochs of bubonic plague outbreaks, particularly in medieval Europe, a specialized figure emerged: the plague doctor. These weren’t typical physicians of their time; instead, they were public health officials contracted by cities to specifically manage and treat the victims of the devastating disease. Unlike general practitioners who often fled in fear of contagion, plague doctors bravely confronted the epidemic head-on, becoming both a symbol of hope and a grim reminder of the pervasive mortality of the era.

The role of a Doctor Bubonic Plague was far from voluntary. Cities and towns, desperate to control outbreaks, employed these doctors through formal contracts. These agreements defined their duties, pay, and the geographical areas they were obligated to serve. A crucial clause in many contracts mandated that plague doctors treat all patients, regardless of their financial status. This commitment to the poorest citizens underscored the public service nature of their position, ensuring that even the most vulnerable received some form of care during these catastrophic times.

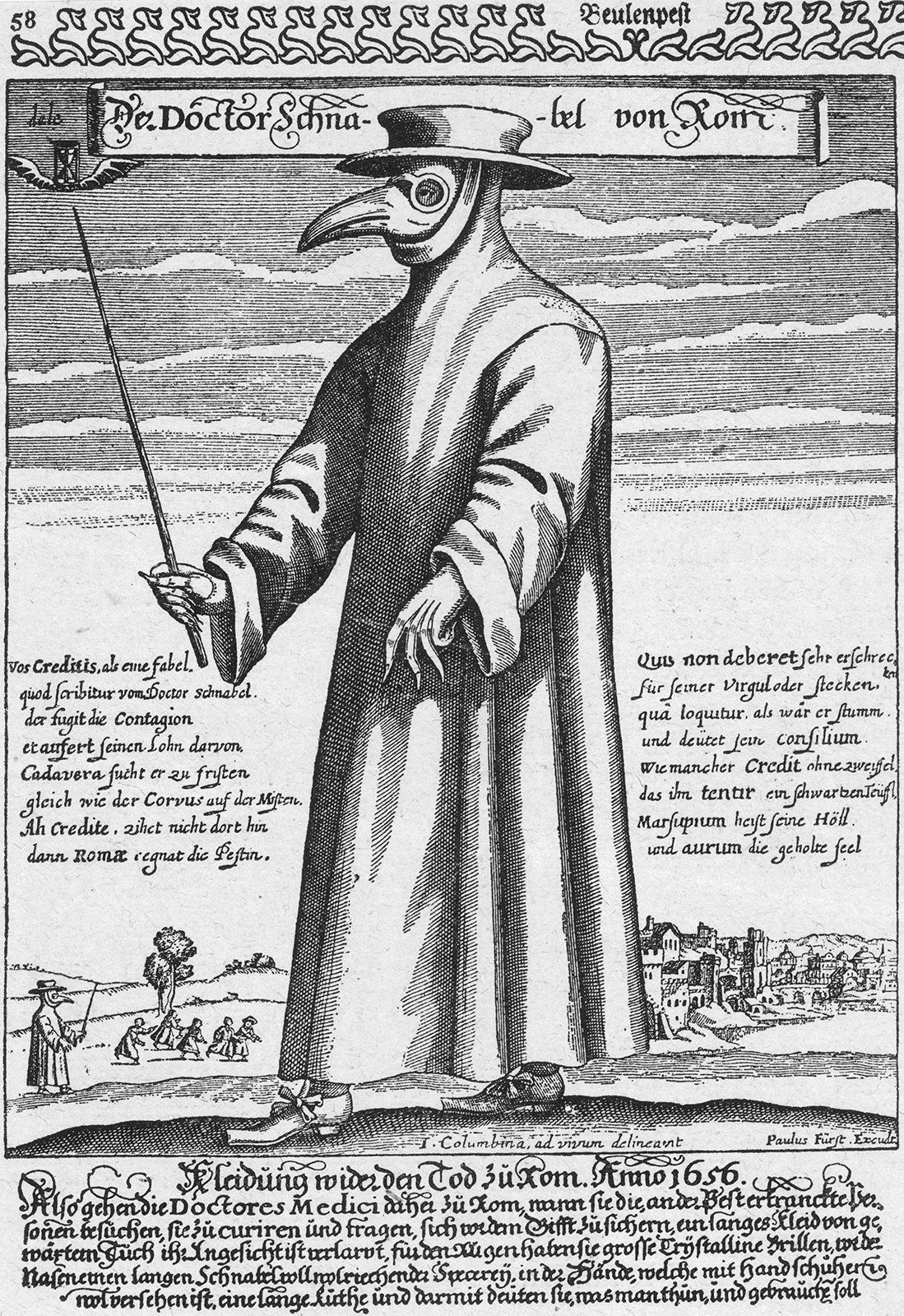

Engraving of a plague doctor in 17th-century protective clothing, including a beaked mask, long coat, and hat, worn during bubonic plague epidemics.

Engraving of a plague doctor in 17th-century protective clothing, including a beaked mask, long coat, and hat, worn during bubonic plague epidemics.

The reasons behind establishing a dedicated corps of doctor bubonic plague were pragmatic. General doctors faced immense risks of infection simply through their regular practice. By assigning specific doctors to plague cases, cities aimed to protect the broader medical community, however, this system was born out of necessity and fear. Many experienced physicians chose to abandon their practices rather than face the plague, creating a vacuum filled by individuals of varying medical backgrounds. Some plague doctors were indeed trained medical professionals, perhaps newly graduated or struggling to find stable work. Yet, a significant number lacked formal medical training altogether. In some instances, those willing to risk their lives tending to the sick were simply individuals who, for various reasons, remained when others fled.

The responsibilities of a doctor bubonic plague extended beyond mere medical intervention. In a time before robust public health infrastructure, they became vital for data collection and civic administration. They were tasked with meticulously recording the grim statistics of infections and deaths, providing crucial information for understanding the epidemic’s progression. Plague doctors also served as witnesses for wills, a necessary function in times of high mortality, and even performed autopsies, rudimentary as they were, in a desperate attempt to understand the disease. Furthermore, many kept journals and casebooks, documenting their observations and attempted treatments. These records, though often based on flawed medical theories, represent early efforts at epidemiological tracking and the search for effective interventions.

Perhaps the most enduring and striking image associated with doctor bubonic plague is their distinctive attire. The iconic costume, which became standardized in the 17th century, was designed to offer protection, albeit based on the limited understanding of disease transmission at the time. This ensemble featured a long, waxed coat, typically made of heavy fabric or leather, worn over leggings and boots, all crafted from leather to minimize potential exposure. Gloves and a wide-brimmed hat completed the outfit, but the most recognizable element was undoubtedly the beaked mask. This mask, often constructed of leather, featured glass or crystal eyepieces to shield the eyes. Plague doctors also carried a wand or staff, used to examine patients and maintain a perceived safe distance without direct contact.

The popular attribution for this peculiar garb often points to Charles de Lorme, a physician to the French court in the early 1600s. Prior to this period, there was no specific uniform for plague doctors. The beaked mask, in particular, became a potent symbol, quickly adopted into popular culture. However, it also became a target of mockery, morphing into a macabre figure of jokes and satirical cartoons. Despite its grim associations, the plague doctor costume found an unexpected place in festive traditions, becoming a popular choice at the Venetian Carnival. It also transitioned into a stock character in the Italian commedia dell’arte, further cementing its cultural presence. Intriguingly, the costume has experienced a modern resurgence in popularity, particularly among costume enthusiasts and during the COVID-19 pandemic, highlighting its enduring symbolic power in times of widespread disease concern.

The beak of the doctor bubonic plague mask was not merely a stylistic choice; it served a purported, albeit misguided, purpose. Medical theory of the time largely subscribed to the concept of “miasma,” the belief that diseases were spread by foul-smelling air. To combat this perceived threat, the beak was filled with intensely aromatic substances. These could include fragrant herbs and flowers like lavender and mint, or stronger-smelling materials such as myrrh, camphor, and sponges soaked in vinegar. Some doctors even employed “theriac,” a complex concoction believed to be a universal antidote since the 1st century CE. While the rationale behind these aromatic fillings was scientifically inaccurate, the practice inadvertently offered some degree of protection. The mask and costume, however unintentionally, created a barrier against infectious bodily fluids and respiratory droplets. Furthermore, the layers of clothing could have offered a degree of protection from flea bites, the actual vector for bubonic plague transmission.

In conclusion, the figure of the doctor bubonic plague is a fascinating and complex product of a terrifying historical period. Born out of necessity during devastating epidemics, they were more than just physicians; they were public servants, data collectors, and symbols of a society grappling with incomprehensible disease. While their medical treatments were largely ineffective by modern standards and rooted in flawed theories, their commitment to caring for the sick, often at great personal risk, remains a compelling testament to human resilience in the face of overwhelming adversity. Their iconic costume, initially intended as protection, has transcended its practical origins to become a lasting and recognizable emblem of disease, death, and, perhaps surprisingly, a morbid form of cultural fascination.