The Black Death. Just the name conjures images of unimaginable suffering and societal collapse. Sweeping across Europe in the Middle Ages, this devastating pandemic instilled terror in populations and spurred desperate measures to combat the invisible enemy. Amidst this chaos emerged a figure both frightening and fascinating: the plague doctor. Contracted by cities to tend to the infected, the plague doctor, with their distinctive and eerie attire, became a symbol of both the era’s medical limitations and humanity’s enduring attempts to confront disease.

Who Were the Black Plague Doctors?

Plague doctors were not the highly esteemed physicians of their time. Instead, they were specifically hired by cities and towns during outbreaks of the bubonic plague, also known as the Black Death, to manage and treat the overwhelming number of plague victims. This was a pragmatic decision. Regular doctors, fearing contagion and often lacking effective treatments, frequently fled plague-stricken areas. To ensure some level of medical response, even if rudimentary, municipalities sought individuals willing to face the epidemic head-on.

These recruits were a mixed bag. Some were indeed trained physicians, perhaps younger doctors or those struggling to establish themselves. Others possessed minimal medical knowledge, or were even charlatans. Desperation and the promise of payment motivated many to take on this perilous role. Their contracts detailed their duties, pay, and crucially, obligated them to treat all citizens, rich and poor alike, in the most afflicted neighborhoods. Beyond basic care, their responsibilities extended to vital public health functions: meticulously recording plague cases and fatalities, documenting wills for the dying, sometimes performing autopsies to understand the disease, and keeping journals that, while often based on flawed theories, contributed to the nascent understanding of epidemics.

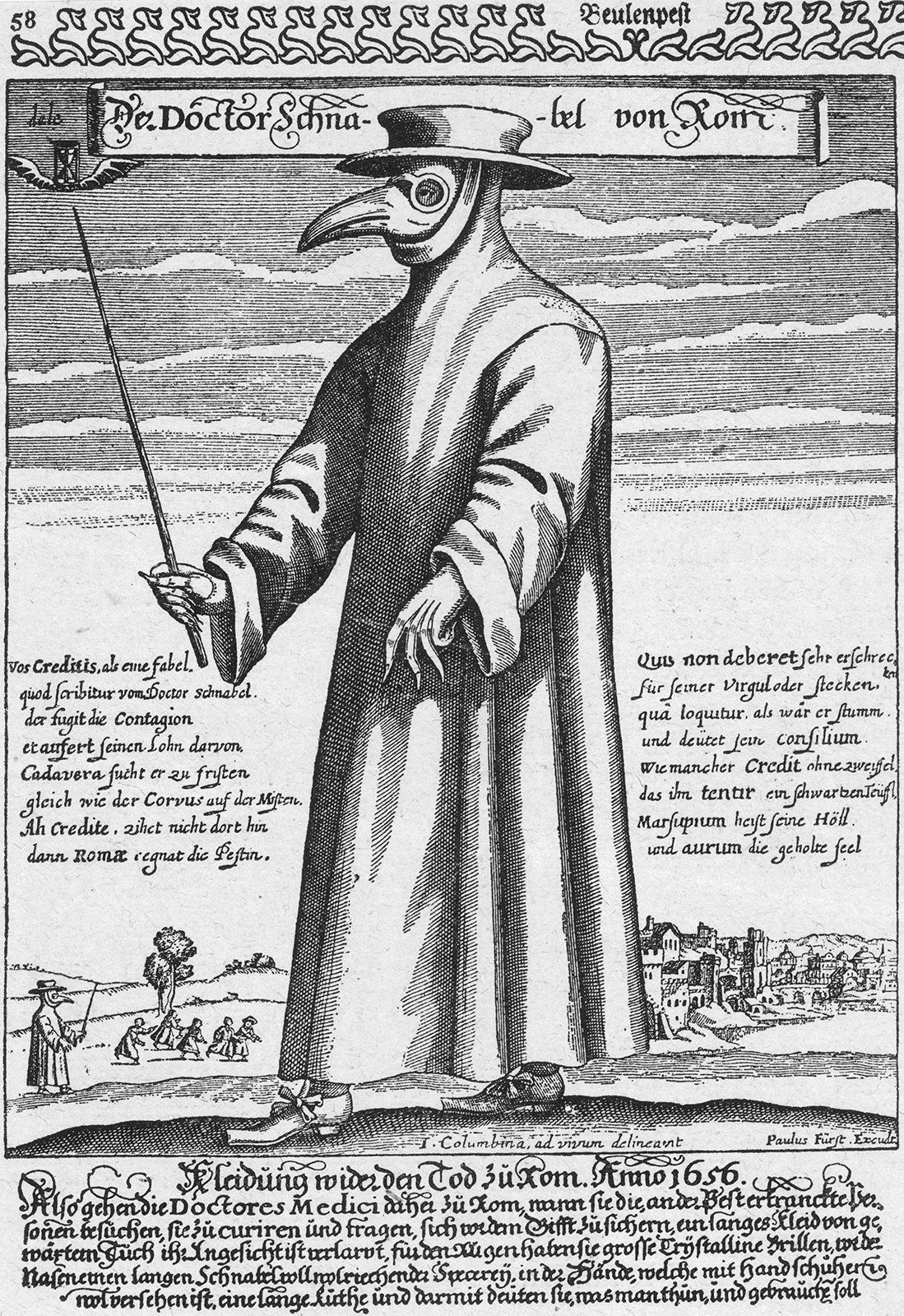

Engraving of a plague doctor in protective clothing, circa 1656

Engraving of a plague doctor in protective clothing, circa 1656

The Macabre Costume of the Plague Doctor

Perhaps the most enduring image of the plague doctor is their unsettling costume. Far from being a standard medical uniform, this attire was conceived as a form of protection against the “miasma” – the foul-smelling air believed to spread disease according to the prevailing medical theories of the time. Developed in the early 17th century and often attributed to Charles de Lorme, a physician to French royalty, the full garb was a sight to behold, and likely, to fear.

The costume consisted of several key components all designed to create a barrier against disease. A long, ankle-length coat, typically waxed for waterproofing, served as the outer layer. Leggings that connected to boots, gloves, and a wide-brimmed hat completed the body covering, often crafted from leather or heavy cloth. But the most striking feature was undoubtedly the beaked mask. This bird-like mask had glass or crystal openings for the eyes and, most importantly, a long beak stuffed with aromatic herbs, spices like lavender and mint, dried flowers, or even sponges soaked in vinegar or camphor. The idea was that these strong scents would counteract the noxious miasma and purify the air the doctor breathed. Plague doctors also carried a wand or staff, used to examine patients and give instructions without direct contact, maintaining what they hoped was a safe distance from infection.

While the miasma theory was incorrect, and the beak’s fragrant stuffing did little to combat airborne viruses or bacteria (which were unknown at the time), the costume inadvertently offered a degree of protection. The full-body covering could shield against infected fleas, which were a primary vector of bubonic plague, and potentially reduce exposure to bodily fluids and respiratory droplets, offering a limited barrier against contagion through contact.

Treatments and the Legacy of the Black Death Doctors

Despite their iconic image, it’s crucial to remember that plague doctors were not miracle workers. Their treatments, rooted in the flawed medical understanding of the era, were largely ineffective against the plague. They often employed practices like bloodletting and draining buboes – the characteristic swollen lymph nodes of bubonic plague – believing these actions would rebalance the body’s humors. They also prescribed medicines to induce vomiting or urination, further attempts to purge the supposed imbalances causing the disease.

These treatments, while reflecting the medical science of the time, did little to cure the plague and could even weaken patients further. However, judging plague doctors solely on their medical ineffectiveness misses a crucial aspect of their role. In a time of societal breakdown and immense fear, they provided a visible, albeit unsettling, presence of authority and care. Their record-keeping, while not leading to immediate cures, contributed to the slow accumulation of knowledge about epidemics.

The image of the plague doctor has persisted through centuries, evolving from a symbol of fear and death to a more romanticized and even fashionable figure. The macabre costume became a popular choice for Venetian Carnival and a stock character in commedia dell’arte. In modern times, especially during the COVID-19 pandemic, the plague doctor costume experienced a resurgence in popularity, reflecting a continued fascination with disease, mortality, and perhaps, a darkly humorous way of confronting fear in the face of widespread illness. The Black Plague Plague Doctor remains a potent reminder of a terrifying chapter in human history and the enduring efforts to find meaning and order in the face of pandemics.