On a day in 1850, within the grand, ornate walls of the Vienna Medical Society’s lecture hall, an event unfolded that would echo through the corridors of medical history, though its significance remained veiled for decades. It was here that Ignaz Semmelweis, a Hungarian obstetrician, stepped forward to present a discovery that, unbeknownst to many in attendance that evening of May 15th, held the power to revolutionize medical practice and save countless lives. His advice, simple yet profound, was distilled into three words: “wash your hands!” This was the core of the message from the Semmelweis Doctor, a message that would eventually transform hospitals and childbirth practices worldwide.

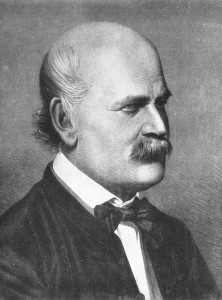

Ignaz Semmelweis

Ignaz Semmelweis

In our contemporary world, the expectation that medical professionals sanitize their hands before any patient interaction is ingrained. Hand hygiene is a cornerstone of modern healthcare, a practice rigorously enforced to prevent the spread of infections. However, the acceptance of this life-saving measure was not always a given. It wasn’t until 1847 that the medical community began to tentatively acknowledge the profound impact of something as simple as handwashing, thanks in large part to the relentless efforts of Dr. Semmelweis.

It was in that year that Dr. Semmelweis began his impassioned campaign at the esteemed Vienna General Hospital (Allgemeines Krankenhaus). He implored his colleagues to adopt handwashing as a mandatory step before examining women in labor. His insistence was not rooted in mere cleanliness; it was a desperate measure to combat a scourge known as “childbed fever,” or puerperal fever. This devastating illness, derived from Latin words meaning “child” and “parent,” was claiming the lives of mothers at alarming rates, and Dr. Semmelweis was determined to understand and eradicate it.

In the mid-19th century, childbirth was inherently risky. Around five out of every 1,000 women died during deliveries attended by midwives or at home. However, the situation was drastically worse in the best maternity hospitals across Europe and America, where deliveries performed by doctors often resulted in maternal death rates that were 10 to 20 times higher. The culprit was almost always childbed fever, a horrific condition characterized by agonizing symptoms. Women suffered from raging fevers, the discharge of putrid pus, excruciating abscesses in the abdomen and chest, culminating in a rapid descent into sepsis and death, often within a mere 24 hours after giving birth.

The cause, while glaringly obvious to us now, remained shrouded in mystery at the time. Medical students and professors at leading teaching hospitals routinely commenced their day by conducting barehanded autopsies on women who had succumbed to childbed fever the previous day. Following these dissections, they would proceed directly to the maternity wards to examine women in labor, unknowingly carrying the seeds of infection with them.

Dr. Semmelweis’s path to his groundbreaking discovery was not straightforward. When he sought a position at the Vienna General Hospital in 1846, he faced prejudice due to his Hungarian and Jewish heritage. In Vienna, medicine and surgery held the highest prestige, but Semmelweis’s background relegated him to the less coveted obstetrics division. Despite this initial setback, it was within this very division that he would make his indelible mark on medical history. Driven by an unwavering commitment to solve the riddle of childbed fever, which was decimating nearly a third of his patients, Dr. Semmelweis, the dedicated doctor, embarked on his quest. He observed that the maternity ward staffed by midwives, who did not perform autopsies, had significantly lower mortality rates, a crucial clue in his investigation.

Each day, Semmelweis was confronted with the heartbreaking pleas of women under his care, begging to be discharged. They perceived the doctors as omens of death, a grim testament to the stark reality of the hospital wards. Crucially, Semmelweis, the observant doctor, listened to his patients, valuing their insights and fears.

This attentiveness led him to a pivotal realization: puerperal fever was being transmitted by doctors. They were acting as vectors, carrying some form of “morbid poison” from the autopsy rooms, where they handled corpses, to the delivery rooms, where they attended to laboring women. This “morbid poison,” as Semmelweis termed it, is now identified as Group A hemolytic streptococcus bacteria.

Streptococcus pyogenes bacteria, seen through a microscope, the cause of puerperal fever.

Streptococcus pyogenes bacteria, seen through a microscope, the cause of puerperal fever.

Historical accounts acknowledge that Semmelweis was not the first to draw a connection between physicians and the spread of puerperal fever, a phenomenon chillingly referred to by expectant mothers as “the doctors’ plague.” Earlier, in 1795, Alexander Gordon, an obstetrician from Aberdeen, Scotland, proposed in his “Treatise on the Epidemic of Puerperal Fever” that midwives and doctors who had recently treated infected women could transmit the disease. Similarly, in 1843, Oliver Wendell Holmes, a Harvard anatomist, published “The Contagiousness of Puerperal Fever,” suggesting that physicians were carriers and recommending that obstetricians refrain from performing autopsies on women who died of puerperal fever.

However, it was Semmelweis, the proactive doctor, who translated this understanding into concrete action. He mandated that his medical students and junior physicians wash their hands in a chlorinated lime solution. This wasn’t a mere rinse; they had to scrub until the lingering odor of decaying flesh, acquired from the autopsy suite, was completely undetectable. Following the implementation of this rigorous handwashing protocol in 1847, the results were dramatic. Mortality rates in the doctor-led obstetrics service plummeted, offering undeniable evidence of the efficacy of Semmelweis’s methods.

Despite the compelling evidence, Semmelweis’s groundbreaking ideas were not universally embraced. In fact, many of his colleagues reacted with outrage and vehement opposition. The suggestion that they, the esteemed physicians, were the cause of their patients’ deaths was deeply offensive and met with considerable resistance and criticism.

Semmelweis himself was not without his complexities. Described as remarkably difficult, he inexplicably delayed publishing his seemingly “self-evident” findings for 13 years, even under persistent encouragement from his supporters. Compounding the situation, he resorted to delivering scathing insults to prominent hospital doctors who dared to question his theories. Such behavior, regardless of provocation, was not easily forgiven within the rigid hierarchy of academic medicine.

As the criticism mounted, Semmelweis grew increasingly embittered and volatile. He ultimately lost his position at the Vienna General Hospital and, in 1850, abruptly returned to his native Budapest, leaving without even informing his closest associates. It was not until 1861 that he finally published his seminal work, “Die Aetiologie, der Begriff und die Prophylaxis des Kindbettfiebers” (“The Etiology, the Concept, and the Prophylaxis of Childbed Fever”). In this publication, he meticulously detailed his theories on childbed fever, advocated for rigorous handwashing as a preventive measure, and launched a fierce, unrestrained attack against his critics, the vehemence of which remains palpable even today.

Tragically, Dr. Semmelweis’s mental state deteriorated further. His behavior became increasingly erratic, leading to his confinement in an insane asylum on July 30, 1865. He died there just two weeks later, on August 13, 1865, at the young age of 47. The circumstances surrounding Semmelweis’s mental breakdown and death remain a subject of historical debate. Some theories suggest he contracted syphilis during an operation, which may have contributed to his mental decline. Others propose blood poisoning and sepsis acquired within the asylum, possibly exacerbated by undiagnosed bipolar disorder. More recent accounts even suggest he might have suffered from early-onset Alzheimer’s disease and was fatally beaten by asylum staff.

Semmelweis’s misfortune was compounded by timing. His pivotal discoveries occurred between 1846 and 1861, a period when the medical world was not yet ready to fully grasp or accept the germ theory of disease.

While Louis Pasteur began exploring the role of bacteria in fermentation in the late 1850s, his groundbreaking work establishing the germ theory of disease largely unfolded between 1860 and 1865. Subsequently, in 1867, Joseph Lister, a Scottish surgeon, unaware of Semmelweis’s contributions, elaborated on the principles of antiseptic surgery, including handwashing with carbolic acid. In 1876, Robert Koch, a German physician, definitively linked a specific germ, Bacillus anthracis, to anthrax, further solidifying the germ theory.

From the early 20th century onwards, however, the medical community and historians have overwhelmingly lauded Semmelweis’s pioneering work. He is now widely recognized and venerated, his name spoken with reverence in medical and public health institutions whenever hand hygiene is discussed. His tragic story serves as a potent reminder of the resistance faced by those who challenge established norms, even when their insights are profoundly life-saving. In his time, Semmelweis, the misunderstood doctor, was dismissed as eccentric, unstable, and a disruptive force within the profession.

Yet, history has unequivocally vindicated Semmelweis. His detractors were undeniably wrong, and he was undeniably right. Dr. Semmelweis paid a heavy personal price for his unwavering dedication to saving lives, pushing the boundaries of medical knowledge in the face of fierce opposition.

On the anniversary of his groundbreaking announcement, it is fitting to celebrate the legacy of this extraordinary Semmelweis doctor. Perhaps the most meaningful tribute we can offer is to wholeheartedly embrace his simple yet revolutionary message: wash our hands often and thoroughly, a practice that continues to save lives every day.