During the devastating plague epidemics that swept through Europe in the Middle Ages, a specialized physician emerged: the Medieval Plague Doctor. These doctors were public health officials contracted by towns and cities to specifically care for individuals afflicted with the plague. In a time of widespread fear and societal disruption, the plague doctor became a recognizable, albeit often misunderstood, figure. Their role extended beyond medical treatment, encompassing vital public health functions during times of crisis.

These physicians operated under a unique contract with the governing bodies. This agreement detailed their duties, compensation, and the geographical areas they were obligated to serve. A crucial aspect of their contract was the commitment to treat all plague victims, irrespective of their social standing or ability to pay. They were often required to venture into the most severely affected neighborhoods, providing care to the poorest and most vulnerable members of society.

The necessity for plague doctors arose from the immense strain the epidemics placed on general practitioners. The risk of contagion was significantly elevated for doctors treating a wide range of ailments, leading many established physicians to flee plague-stricken areas. This exodus left a void filled by individuals who, for various reasons, remained and stepped into the role of plague doctors. While some were indeed trained medical professionals, perhaps newly graduated or struggling to find stable work, others possessed limited to no formal medical training. For some, the dire circumstances and the promise of employment were the primary motivators, regardless of their medical background.

Beyond administering treatments, plague doctors undertook a range of civic duties crucial to managing the crisis. They were tasked with meticulously recording the number of plague cases and fatalities, documenting the grim toll of the epidemic. Their responsibilities also included acting as witnesses for wills, a necessary function in times of high mortality, and even performing autopsies to better understand the disease. Many plague doctors maintained journals and casebooks, diligently documenting their observations and attempted treatments. These records, though often based on flawed medical understanding, contributed to the gradual accumulation of knowledge about the plague and potential interventions.

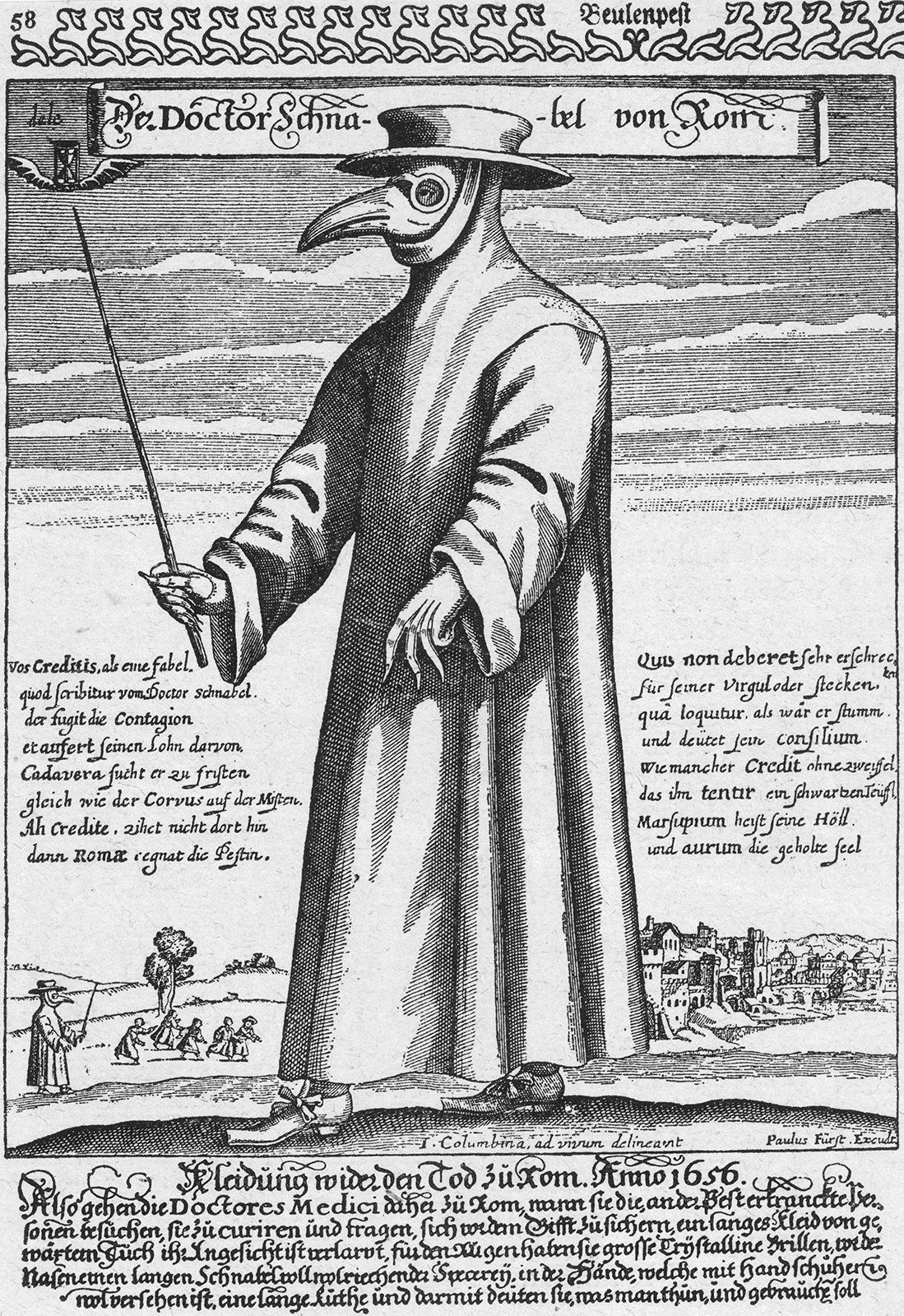

Engraving of a medieval plague doctor wearing protective clothing including a beaked mask, gloves, and a long coat, circa 1656.

Engraving of a medieval plague doctor wearing protective clothing including a beaked mask, gloves, and a long coat, circa 1656.

The treatments employed by medieval plague doctors reflected the limited medical knowledge of the era and were largely ineffective against the plague. Influenced by the prevailing theory of humoralism, treatments often aimed to rebalance the body’s supposed humors. Common practices included bloodletting and draining fluids from buboes, the characteristic swellings associated with bubonic plague. Doctors also prescribed various concoctions intended to induce vomiting or urination, all in the belief of purging the body of imbalances. These methods, while well-intentioned within the contemporary medical framework, did little to combat the bacterial infection itself.

Perhaps the most enduring and striking image of the plague doctor is their distinctive and somewhat unsettling attire. The iconic costume, which became standardized in the 17th century, consisted of several key components designed, according to the beliefs of the time, to offer protection against the disease. This ensemble typically included a long, ankle-length coat or gown made of waxed fabric or leather, worn over leggings that were connected to boots, gloves, and a wide-brimmed hat. The most recognizable element was the peculiar beaked mask, often fitted with glass or crystal eyepieces to shield the eyes. Plague doctors also carried a wand or staff, used to examine patients and their clothing without direct contact, and to maintain what was considered a safe distance from potentially infectious individuals. While the costume is often attributed to Charles de Lorme, a physician serving the French court in the early 17th century, it is important to note that earlier plague doctors did not have a standardized uniform.

The mask’s beak was not merely a stylistic choice; it served a perceived protective function. Adhering to the miasma theory, which posited that disease spread through foul-smelling air, the beak was filled with aromatic substances. These often included strong-smelling herbs and flowers like lavender, mint, and rosemary, as well as materials like myrrh, camphor, or sponges soaked in vinegar. Some doctors even filled the beak with theriac, a complex mixture of herbs and other ingredients that was considered a universal antidote for various ailments. While the miasma theory itself was inaccurate, the plague doctor’s costume inadvertently offered a degree of protection. The full-body covering could shield against infected flea bites and contact with infectious bodily fluids and respiratory droplets, offering a barrier against the actual modes of plague transmission, even if unknowingly.

The distinctive appearance of the plague doctor, particularly the beaked mask, quickly permeated popular culture. It became a subject of dark humor and satire, with plague doctors depicted in macabre jokes and cartoons as grim figures foreshadowing disease and death. Despite its somber associations, the costume gained a surprising popularity at the Venetian Carnival, becoming a recurring and recognizable guise. The plague doctor also emerged as a stock character in the Italian commedia dell’arte, further solidifying its place in the cultural imagination. Interestingly, in contemporary times, the plague doctor costume has experienced a revival, particularly among costume enthusiasts and during the COVID-19 pandemic, reflecting a renewed fascination with this historical figure and their haunting legacy.

In conclusion, the medieval plague doctor was a product of extraordinary times. Tasked with managing a terrifying and poorly understood disease, they represent a complex intersection of historical medicine, public health, and cultural symbolism. While their treatments were largely ineffective and their understanding of disease transmission was flawed, they played a crucial role in providing care, documenting the epidemic, and offering a semblance of order during periods of widespread chaos and fear. The iconic image of the plague doctor, especially their beaked mask, continues to resonate today, serving as a potent reminder of past pandemics and the enduring human struggle against disease.