The doctor’s white coat, a garment seemingly simple, carries a weight of symbolism rivaled only by a priest’s clerical collar in the professional world. Emerging in the late 19th century, initially donned by surgeons and then physicians, the Doctor White coat served as a clear visual differentiator. It separated those practicing evidence-based medicine from the dubious practices of quacks and snake-oil salesmen prevalent at the time. This marked the beginning of the white coat’s association with medical legitimacy and expertise.

Today, the white coat evokes a spectrum of interpretations. For many, it remains a potent symbol of professionalism, unwavering integrity, and a deep-seated commitment to the well-being of patients. It signifies the dedication of healthcare professionals to caring for the sick and vulnerable. Conversely, for others, the doctor white coat can represent elitism, a barrier to patient connection, and ironically, a potential source of germ transmission. This duality highlights the complex and evolving perception of this iconic garment in modern medicine.

While almost every medical school in the United States, approximately 97%, conducts a white coat ceremony to welcome incoming students, the actual utilization of the white coat in clinical environments is far from uniform. Specialties like pediatrics and psychiatry have increasingly voiced concerns about the white coat, with some practitioners opting to forgo it entirely, believing it can be intimidating or create a distance between them and their patients. Even prestigious institutions like the Mayo Clinic advocate for business attire alone, aiming to foster a more approachable and less hierarchical doctor-patient relationship.

Groundbreaking research, the most extensive of its kind to date published in BMJ Open, investigated patient perceptions of physician attire. Researchers at the University of Michigan surveyed 4,000 patients across 10 prominent U.S. academic medical centers. The findings revealed that what a physician wears significantly impacts patient perceptions of their doctor’s competence and their overall satisfaction with care. Physicians who chose to wear a white coat over formal business attire – defined as a navy blue suit and dress shoes – were consistently perceived as more knowledgeable, trustworthy, empathetic, and approachable, particularly among patients aged 65 and older. Doctors in scrubs paired with a white coat ranked second highest in patient preference, followed by those in business attire without a coat. Interestingly, in specific settings like operating rooms and emergency departments, a preference emerged for doctors wearing scrubs alone, suggesting context-dependent perceptions of professional dress.

Dr. Christopher Petrilli, assistant professor of hospital medicine at the University of Michigan Medical School and the lead author of the study, emphasizes the simplicity of adjusting physician attire. “What we wear is such an easy thing to modify,” he states. “At a time when we’re all trying to be more patient-centered, doesn’t it make sense to do what people want?” This perspective underscores the potential for simple changes in dress code to enhance patient comfort and trust.

The Germ Factor: Image vs. Infection Control in Doctor’s Attire

However, not everyone agrees that patient preference should dictate physician attire. Dr. Mike Edmond, chief quality officer and clinical professor of infectious diseases at University of Iowa Hospitals and Clinics, questions the validity of directly asking patients about their preferred doctor’s clothing. “Asking patients what they want doctors to wear isn’t even a valid question,” he argues. “No patient picks their doctor that way.” He recounts an anecdote from early in his career, wearing jeans for a paperwork-focused day when a patient required his attention. His apology for not wearing “doctor clothes” was met with the patient’s reassuring words: “I don’t care if you are in your pajamas. I just want you to help me.” This highlights the primacy of competence and care over attire in the patient-doctor relationship.

A significant counterpoint to the symbolic advantages of the white coat is the well-documented evidence of it harboring potentially harmful microorganisms. Studies have consistently shown that doctor white coats, particularly around the cuffs and pockets, can be reservoirs for bacteria and viruses. Following an initial study in the UK in 1991, numerous subsequent investigations have confirmed the germ-carrying potential of white coats. By 2007, the BBC declared the white coat “more or less dead” in terms of its hygienic viability. In 2008, the UK’s National Health Service, already wary of the white coat as a barrier to patient interaction, mandated that physicians who insisted on wearing them must be bare below the elbows to reduce contamination risks. The debate reached such prominence that in 2009, the American Medical Association even considered a potential ban on white coats within hospital settings.

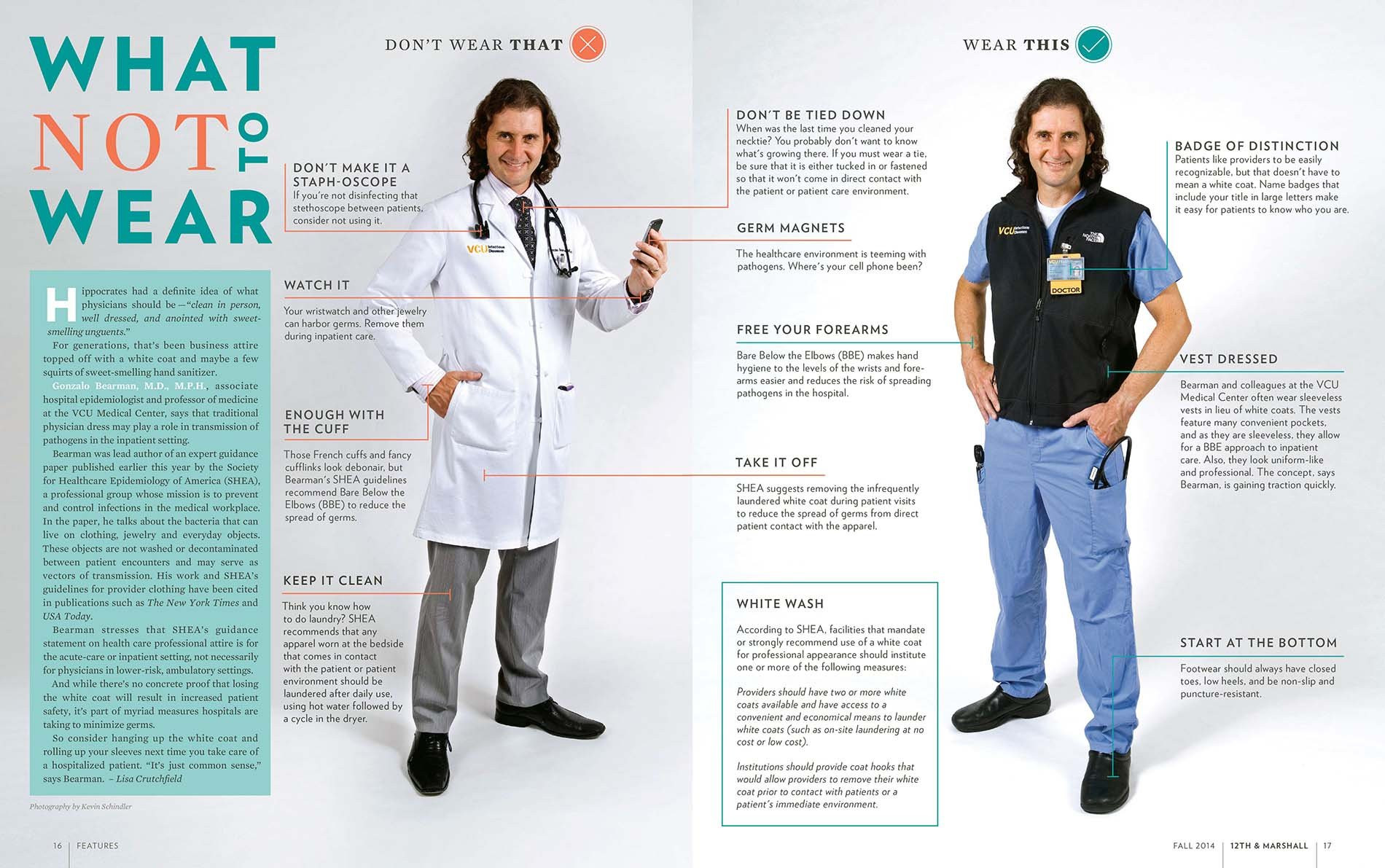

Comparison of doctor's attire: white coat versus alternative vest at Virginia Commonwealth University School of Medicine.

Comparison of doctor's attire: white coat versus alternative vest at Virginia Commonwealth University School of Medicine.

Virginia Commonwealth University School of Medicine provides guidance on doctor’s attire, suggesting alternatives like a sleeveless black neoprene vest to balance warmth and hygiene.

The frequency of laundering also contributes to the hygiene concerns. While almost every other item that comes into contact with patients is rigorously sanitized or disposed of, doctor white coats are often washed infrequently. Studies indicate that doctors typically launder their lab coats approximately once every 12 days, and a concerning 70% of physicians admitted to inconsistent laundering of their neckties, another potential source of germ transmission.

Some infectious disease specialists propose a simpler solution: rolling up sleeves. While acknowledging the lack of definitive proof linking white coat germs to patient infections, they point to studies showing reduced cross-contamination with short sleeves. A 2017 study led by Dr. Amrita John, an infectious disease specialist at University Hospitals Cleveland Medical Center, demonstrated that long sleeves significantly contribute to cross-contamination. The study, involving 34 healthcare workers wearing coats with both long and short sleeves and using dummies contaminated with a harmless virus, found that 25% of long-sleeved coats became contaminated, and 5% transferred the virus to clean dummies.

Dr. John advocates for a balanced approach, recalling her medical training in India where minimizing barriers between doctors and patients was prioritized. However, she acknowledges the societal expectation of doctors wearing white coats. As a practical compromise, she supports short-sleeved white coats, citing both climate considerations from her medical school days and the crucial need to prevent pathogen transmission in contemporary healthcare.

“In my medical school training in India, we didn’t want to have a barrier between patients and us. But it’s true many people expect doctors to wear [white coats].”

Dr. Amrita John, University Hospitals Cleveland Medical Center

Virginia Commonwealth University School of Medicine has taken a proactive stance by offering doctors a sleeveless black neoprene vest. According to Dr. Gonzalo Bearman, chair of the division of infectious diseases at VCU, this vest addresses the practical needs of pockets and warmth associated with the white coat while mitigating infection risks. The choice of black aligns with the university’s colors, and the initiative has achieved a high compliance rate with bare-below-the-elbows guidelines without strict enforcement. While Dr. Bearman notes the lack of direct evidence linking this to reduced infections, he emphasizes it as a “common-sense intervention.”

Beyond Germs: White Coat Syndrome and Medical Hierarchy

Alternatives to the traditional white coat may also offer benefits beyond infection control, potentially alleviating “white coat syndrome.” This phenomenon, documented since 1896, describes the anxiety-induced elevation of blood pressure readings in up to 30% of patients simply due to being in a medical setting. Emerging research challenges the perception of white coat syndrome as benign. A mortality study published in the New England Journal of Medicine revealed that patients with white coat hypertension face twice the mortality risk compared to individuals with normal blood pressure, underscoring the potentially serious health implications of this anxiety response.

Furthermore, the traditional hierarchy symbolized by white coat length is also being re-evaluated. Historically, first-year residents wore shorter, hip-length white coats, transitioning to longer, knee-length coats after their initial year. While subtle to patients, this distinction was significant within the medical community. However, this tradition is facing scrutiny, particularly at institutions like the Osler Medical Residency Training Program at The Johns Hopkins Hospital, the oldest residency program in the US.

Responding to concerns from new doctors, Johns Hopkins has abandoned the practice of requiring short white coats for first-year residents. These residents felt the shorter coat established an unnecessary hierarchy, placing them below more senior residents and attending physicians. Dr. Sanjay Desai, director of the residency program at Johns Hopkins (and a white coat advocate), explains the historical rationale behind the short coat: it symbolized that earning an MD was not synonymous with being a fully-fledged clinician, and the first year was primarily a learning period.

Students interpreted the short white coat “as a physical symbol of hierarchy and rigidity, so we eliminated it. Our values haven’t changed. But I am perfectly willing to compromise on symbols.”

Dr. Sanjay Desai, Johns Hopkins Hospital

Dr. Desai acknowledges that contemporary students perceived the short white coat as a symbol of “hierarchy and rigidity,” leading to its elimination. He emphasizes that the program’s core values remain unchanged, but a willingness to adapt symbolic traditions is necessary to foster a more inclusive and collaborative environment.

This shift towards egalitarianism resonates with younger generations who often favor less formal attire and aligns with concerns about patient safety. Dr. Edmond argues that hierarchical dress codes can hinder communication, potentially preventing junior doctors in short coats from speaking up when they observe senior doctors in long coats making errors.

The Future of the Doctor White Coat: Evolution, Not Extinction

Will the doctor white coat disappear entirely? Probably not in the near future. However, the ongoing debate and re-evaluation of its symbolism and practical implications are undeniable. Dr. Paul Sax, an infectious disease specialist at Brigham and Women’s Hospital in Boston, notes the passionate and often polarized responses he receives when discussing the white coat issue online, indicating the continued relevance and emotional weight associated with this garment.

Ultimately, personal preference plays a significant role. Dr. Desai, while acknowledging the evolving perspectives, remains a white coat proponent. “I don’t wear it every day,” he says, “but I do when I am in front of patients. It’s part of the process for me. It’s almost a uniform for when we want to help patients feel better.” This sentiment reflects the enduring appeal of the doctor white coat as a symbol of the healing profession, even as its role and interpretation continue to evolve in the 21st century.