During periods of widespread disease outbreaks, particularly throughout the Middle Ages in Europe, the specter of the “plague doctor” emerged. These weren’t your typical physicians; they were specialized doctors contracted by cities and towns to specifically manage and treat victims of the plague. These contracts were formal agreements outlining their duties, the geographical areas they would cover, their compensation, and importantly, a commitment to care for all, regardless of social standing, even those who were impoverished and unable to pay.

In times of plague, general practitioners faced heightened risks of infection from everyday exposure. Therefore, designating specific doctors to handle plague cases was considered a safer approach for the broader medical community. However, many established and experienced doctors often fled urban centers to avoid the plague, leaving a void. This resulted in a situation where many Plague Doctors were either newly trained, less experienced doctors who struggled to find other work, or in some cases, individuals with no formal medical training at all, but who were willing to engage directly with plague sufferers when others were not. The role of the plague doctor extended beyond just medical treatment. They were also tasked with crucial public health functions, such as meticulously recording the numbers of plague cases and deaths, acting as witnesses for wills, sometimes performing autopsies to understand the disease, and diligently maintaining journals and casebooks. This documentation was vital for tracking the epidemic and attempting to develop effective treatments or preventative strategies for the future.

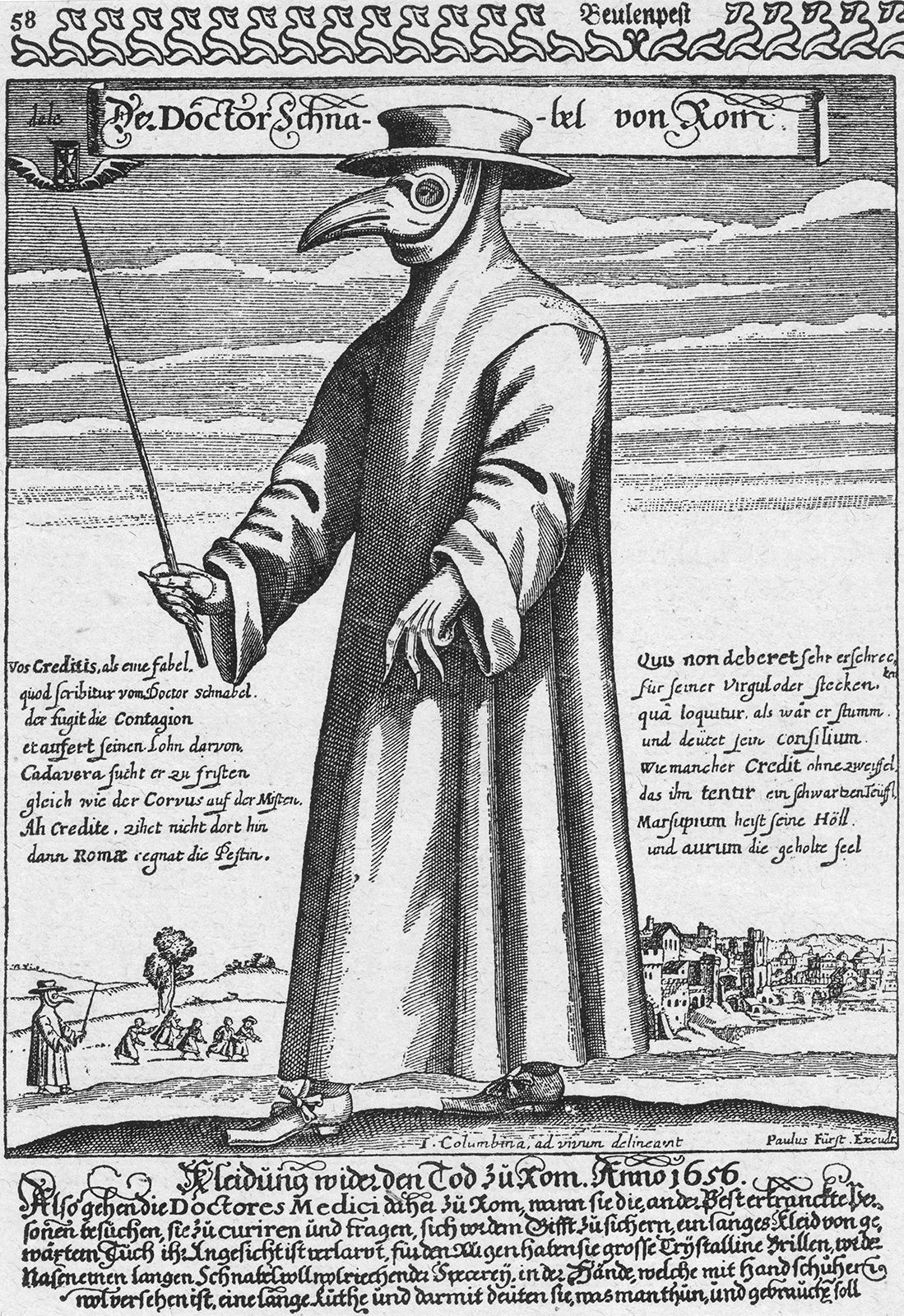

A 17th-century engraving depicts a plague doctor in full protective gear, circa 1656.

A 17th-century engraving depicts a plague doctor in full protective gear, circa 1656.

During the medieval plague epidemics, understanding of disease transmission was rudimentary. Consequently, the medical interventions provided by plague doctors were often based on prevailing theories rather than effective practices and were largely ineffective against the plague itself. Common treatments included bloodletting and draining fluids from buboes, the characteristic swellings associated with bubonic plague. Doctors also prescribed emetics to induce vomiting and diuretics to promote urination. These treatments were rooted in the ancient Greek theory of humorism, which posited that the body’s balance of four humors (blood, phlegm, yellow bile, and black bile) needed to be restored to combat illness.

Perhaps the most enduring and striking image of the plague doctor is their distinctive and somewhat unsettling attire. This iconic costume consisted of a long, ankle-length coat typically waxed for protection, leggings that connected to boots, gloves, and a wide-brimmed hat. The most recognizable feature was the beaked mask, equipped with glass or crystal eyepieces to shield the eyes. Plague doctors also carried a wand or staff. This tool served a dual purpose: it allowed them to examine and direct patients without direct physical contact, and to maintain what they believed was a safe distance from potentially infectious individuals. While earlier plague outbreaks did not feature a specific uniform, this particular costume design is largely attributed to Charles de Lorme, a 17th-century French physician who served the royal court. The macabre appearance of the plague doctor and their costume quickly made them figures of both fear and dark humor. They became recognizable symbols of death and disease, often featured in jokes and satirical cartoons. The costume also gained a life beyond its practical (or impractical) origins, becoming a popular choice for masquerades, particularly at the Venetian Carnival, and a recurring stock character in the Italian commedia dell’arte. Intriguingly, the plague doctor costume has seen a resurgence in modern times, especially during the COVID-19 pandemic, adopted by costume enthusiasts and as a symbolic, if somewhat grim, commentary on contemporary epidemics.

The long beak of the plague doctor’s mask was not merely for show. It was designed to be filled with strong-smelling aromatic items. These usually included herbs like lavender and mint, flowers, or other potent substances like myrrh, camphor, or sponges soaked in vinegar. Some doctors even filled the beak with theriac, a complex and widely used medicinal concoction believed to be a cure-all since the 1st century CE. This practice stemmed from the prevailing medical theory of miasma. It was believed that diseases were spread through “miasma,” or foul-smelling air, which disrupted the balance of bodily humors. The strong aromas in the beak were intended to act as a protective barrier against this bad air. Ironically, while the reasoning was based on a flawed understanding of disease transmission, the plague doctor’s costume, in practice, likely offered a degree of protection. The full-body covering could have helped shield the wearer from infected bodily fluids and respiratory droplets, and potentially even from bites from infected fleas, which were vectors for the bubonic plague.