Superstition is the poison of the mind

– Joseph Lewis

The grandeur of Rome and the glory of Greece, pioneers of early medical understanding, waned with the fall of the Roman Empire in the 5th century AD. While these ancient civilizations had propelled medical knowledge forward, the subsequent era, often termed the Middle Ages, witnessed a regrettable lull in artistic, cultural, and scientific advancement compared to both preceding and succeeding periods. Medical progress, in particular, faced stagnation for centuries, only beginning to re-emerge in the 17th and 18th centuries.

The mantle of Western learning shifted eastward to Constantinople, present-day Istanbul, the heart of the Byzantine Empire. This empire, having embraced Christianity since the 4th century under Emperor Constantine, saw the Church rapidly expand its influence and authority across Western Europe.

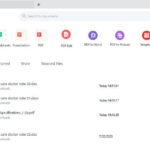

The Roman Catholic Church became the dominant force shaping the trajectory of the medical world. Any perspective diverging from established Church doctrine was swiftly condemned as heresy and met with punitive measures. The Church propagated the view that illness was divine retribution for sin, a consequence of moral failing. This interpretation went unchallenged, becoming the accepted paradigm. Suffering was woven into the fabric of the human experience. As spiritual concerns took precedence, bodily health was relegated to the realm of faith, and medical prescriptions often blurred into prayers. Superstition permeated medical thought, with disease origins and cures attributed to destiny, sin, and celestial influences. Consequently, the Middle Ages lacked a robust tradition of scientific medicine, where observation was inextricably linked with spiritual and religious interpretations. Medieval medicine became an amalgam of inherited classical ideas and prevailing spiritual beliefs. The bedrock of medical knowledge rested largely on surviving Greek and Roman texts, diligently preserved within monasteries and other repositories of learning.

Bleeding a patient

Bleeding a patient

Echoes of Classical Antiquity in Medieval Medical Practice

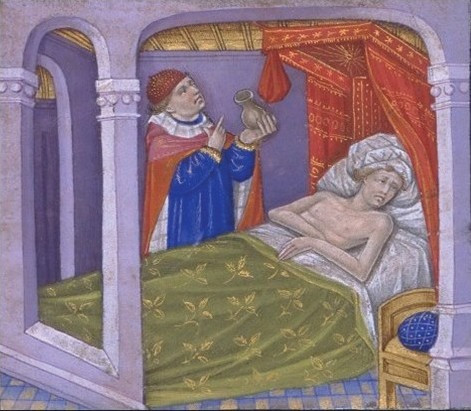

Despite the shift in societal structures and beliefs, medieval medical practice remained firmly rooted in the traditions of classical Greece. The ancient concept of the body’s composition, based on the four humors – yellow bile, phlegm, black bile, and blood – persisted. These humors were believed to be governed by the four elements: fire, water, earth, and air. Disease was seen as a manifestation of humoral imbalance, and treatments aimed at restoring equilibrium through purging excess humors. Bloodletting, cupping, and leeching, practices inherited from antiquity, were common therapeutic interventions throughout the Middle Ages. The notion that an excess of blood was the root of many ailments made bloodletting a seemingly logical and widely applied cure. Diet also held a prominent place in medieval treatment. The understanding of food’s impact on health, articulated by Hippocrates with his famous adage, “Let food be thy medicine and medicine be thy food,” continued to resonate.

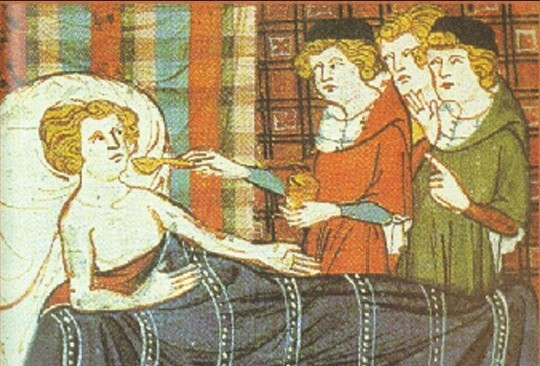

The Greek humoral theory, refined by Galen, evolved into a comprehensive framework for understanding temperament, encompassing psychological and social traits alongside physical characteristics. An excess of each humor was associated with specific temperaments: sanguine (blood), phlegmatic (phlegm), choleric (yellow bile), and melancholic (black bile). Medieval Doctors, however, were not without diagnostic skills. Observation, palpation, pulse-taking, and urine examination were their primary tools. Manuscripts often depict physicians meticulously examining urine flasks or feeling patients’ pulses. A doctor’s initial assessment involved observing appearance, listening to symptoms, feeling the pulse, and scrutinizing urine. Urine inspection was paramount, and the urine flask became the quintessential symbol of the medieval doctor, much like the stethoscope in modern medicine.

Medieval doctors used the color of urine to diagnose an illness. Physician examining a urinal

Medieval doctors used the color of urine to diagnose an illness. Physician examining a urinal

The belief in the celestial influence of the moon and planets on health, a tenet of classical antiquity, persisted in the Middle Ages. It was believed that the human body and celestial bodies shared the same four elemental composition. Health depended on the harmonious balance of these elements within the body, a balance purportedly affected by lunar and planetary positions. The moon, in particular, was thought to exert significant influence on bodily fluids and the four elements. Astrological knowledge was considered crucial for diagnosis and treatment decisions. Physicians consulted astronomical charts, including the Zodiac Chart, to determine auspicious times for treatment, particularly for procedures like bloodletting, believed to be influenced by lunar and planetary cycles. These charts served as medical guides, advising against specific interventions for individuals born under certain astrological signs.

Galen’s Enduring Influence on Medieval Medical Thought

Galen, the towering figure of ancient medicine, held unchallenged authority throughout the Middle Ages. His pronouncements on medical matters were treated as dogma. He provided detailed descriptions of the four cardinal signs of inflammation – redness, pain, heat, and swelling – and significantly advanced the understanding of infectious diseases and pharmacology. However, Galen’s anatomical knowledge was flawed, being based on animal dissections, primarily of apes, sheep, goats, and pigs, rather than humans. Paradoxically, some of Galen’s theories inadvertently hindered medical progress. His notion of blood carrying “pneuma,” or life spirit, giving it its red hue, coupled with the mistaken belief that blood traversed a porous wall between heart ventricles, delayed the comprehension of blood circulation and discouraged physiological research. Nonetheless, Galen’s contributions to muscle form and function, spinal cord anatomy, diagnosis, and prognosis were immense. His writings served as the conduit for transmitting Greek medical knowledge to the Western world via Arab scholars, solidifying his lasting impact.

The Medieval Apothecary: A Realm of Medicinal Plants

“How can a man die who has sage in his garden?”

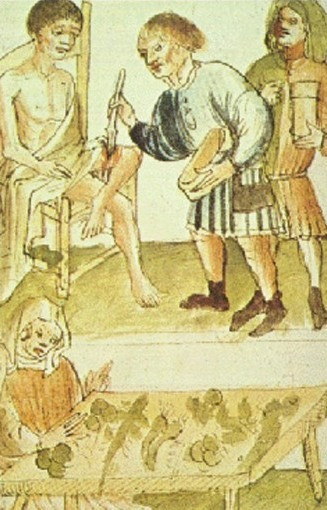

Herbs, flowers, and fragrances were integral to medieval life, intertwined with both magic and medicine. Medicinal plants and herbs formed the cornerstone of medieval pharmacopeia. Remedies were concocted from herbs, spices, and resins. Dioscorides, a Greek physician, penned his Materia Medica around 65 AD, a practical guide detailing the medicinal applications of over 600 plants. Though the original text is lost, numerous copies survive, and Dioscorides’ work became the bedrock of herbal medicine until around 1500. Some plants were specific to certain ailments, while others were touted for their panacean properties. Often, remedies were complex mixtures of multiple herbs.

The Saxon Leech Book of Bald, dating from around AD 900–950, is the oldest surviving English herbal manuscript. It reveals the prevalence of vapor and herb baths for diverse conditions and the common practice of “smoking” the sick with fragrant woods and plants. Scented garlands adorned homes, and every herb, tree, and flower was imbued with unique qualities. Among scents, the rose held a special significance in the Middle Ages. Crusaders returning from the Middle East introduced various perfumes, including rosewater, which became a luxury for the nobility, used for handwashing after meals. Rose petals also perfumed baths.

Monasteries were centers for the study of medicinal plants. Monks cultivated and experimented with plants described in classical texts in their monastic gardens, an essential component of any monastery. The sick sought healing herbs from monasteries, local herbalists, or apothecaries. Monasteries developed extensive herb gardens for producing herbal cures, which remained part of folk medicine and were also utilized by some professional physicians. Monks, skilled in manuscript production and tending to both gardens and the sick, compiled books of herbal remedies. However, much of this work mirrored and reiterated classical texts. Pliny’s Naturalis Historia, encompassing myths, folklore, trees, and medicinal plants (circa 77–79 AD), and Dioscorides’ De Materia Medica were frequently cited, and their translations were widely copied throughout the Middle Ages.

Medieval doctor's blood letting blades

Medieval doctor's blood letting blades

Doctors giving medicine

Doctors giving medicine

Common ailments were treated with readily available herbs. Headaches and joint pain were addressed with fragrant herbs like rose, lavender, sage, and hay. Henbane and hemlock mixtures were applied to aching joints. Coriander was used to reduce fever. Wormwood, mint, and balm were remedies for stomach pains and sickness. Lung problems were treated with liquorice and comfrey. Cough syrups and drinks were prescribed for chest colds, head colds, and coughs. Wounds were cleansed, and vinegar was widely employed as a disinfectant, believed to eradicate disease. Mint was used to treat venom and wounds, while myrrh served as an antiseptic for wounds.

Notably, medieval herbal medicine lacked rigorous experimentation to validate the efficacy of treatments. Success was attributed to the herbs’ supposed action on humors and the belief that such natural remedies were divinely intended for healing. Origen, an early Christian theologian, stated, “For those who are adorned with religion use physicians as servants of God, knowing that he himself assigned both herbs and other things to grow on the earth.” This fusion of medicine and religion, medical thought and theological considerations, is a defining characteristic of the medieval period.

The doctrine of signatures, a philosophy embraced by herbalists from Dioscorides to Galen, further shaped herbal usage. This doctrine posited that herbs resembling body parts could treat ailments of those parts. For instance, lungwort, used for tuberculosis, has spotted leaves resembling diseased lungs. The Church provided a theological justification, suggesting that God provided remedies for every ailment, marked by a “signature” indicating their purpose. This, however, is now recognized as superstition, lacking scientific basis for plant shapes and colors indicating medicinal properties.

The Black Death: A Cataclysmic Challenge to Medieval Medicine

“… and so many died that all believed it was the end of the world.”

The Plague in Siena: An Italian Chronicle

The Black Death, one of history’s most devastating pandemics, originated in China or Central Asia before spreading westward. It ravaged the Mediterranean and Europe in the 13th and 14th centuries. By 1349, it had decimated one-third of the Islamic world and is estimated to have killed 30–60% of Europe’s population. Europe took 150 years to recover demographically. The plague recurred intermittently until the 19th century. Its aftermath triggered profound religious, social, and economic upheavals, reshaping European history.

The Black Death arrived in Europe in October 1347, carried by twelve Genoese trading ships docking at Messina, Sicily, after a Black Sea voyage. Dockworkers were met with a gruesome sight: most sailors were dead, and survivors were gravely ill with fever, vomiting, delirium, and covered in black, oozing boils – the signature “plague-boils.” Sicilian authorities hastily expelled the “death ships,” but it was too late. The Black Death would claim over 20 million European lives within five years, nearly a third of the continent’s population.

Rumors of a “Great Pestilence” preceded the ships’ arrival, reaching Europe from trade routes across the Near and Far East, where the disease had already struck China, India, Persia, Syria, and Egypt in the early 1340s. However, Europeans were unprepared for the Black Death’s horrific reality.

Italian poet Giovanni Boccaccio vividly described the symptoms:

“In men and women alike at the beginning of the malady, certain swellings, either on the groin or under the armpits ¼ waxed to the bigness of a common apple, others to the size of an egg, some more and some less, and these the vulgar named plague-boils. Blood and pus seeped out of these strange swellings, which were followed by – fever, chills, vomiting, diarrhea, terrible aches and pains – and then, in short order, death ¼ the mere touching of the clothes appeared to itself to communicate the malady to the toucher.”

The Black Death’s terrifying contagiousness meant death could strike overnight.

Medieval society lacked the medical understanding to combat this disease. Bacteria and contagion were unknown concepts. Medieval doctors attributed the plague to a “pestilential atmosphere,” caused by planetary alignments or preceding earthquakes and volcanic eruptions. Treatments were crude and ineffective: bloodletting, boil-lancing (dangerous and unsanitary practices), and superstitious measures like burning aromatics and bathing in rosewater or vinegar. Some even advised against olive oil consumption and bathing. Believing the air was “stiff,” loud noises were employed – bells, gunshots, and releasing birds indoors.

In the face of incomprehensible horror, people turned to prayer and pilgrimage. The Church declared the Black Death divine punishment for humanity’s sins. People implored Christ, the Virgin Mary, and saints for intervention. Penitent flagellants whipped themselves, a practice still re-enacted in some Catholic countries during Holy Week, seeking divine mercy. Faith, though potent comfort, offered no cure.

Plague doctor

Plague doctor

Modern medicine understands the Black Death, or plague, is caused by the bacterium Yersinia pestis, discovered by Alexandre Yersin in the late 19th century. Transmission occurs through air, saliva, and infected flea and rat bites. Medieval Europe, teeming with rats and fleas, particularly on ships, facilitated the plague’s rapid spread from port to port. From Messina, it reached Marseilles, Tunis, Rome, and Florence, then Paris, Bordeaux, Lyon, and London by mid-1348.

This sequence, clear to modern understanding, was utterly baffling in the 14th century. Transmission mechanisms were unknown. One doctor theorized “instantaneous death occurs when the aerial spirit escaping from the eyes of the sick man strikes the healthy person standing near and looking at the sick.” Prevention and treatment were nonexistent.

Panic seized populations. Healthy individuals shunned the sick. Doctors and priests refused their duties. Shops closed. Flight to the countryside proved futile, as the disease affected animals too. Desperate self-preservation led to abandonment of the sick and dying. Boccaccio lamented, “Each thought to secure immunity for himself.”

The Black Death epidemic subsided by the early 1350s, but plague recurred for centuries. Modern sanitation, public health, and antibiotics have dramatically reduced its impact, but not eradicated it. Plague still occurs, affecting fewer than 3000 people annually worldwide, and remains deadly if untreated.

This man's leg wound is being treated, while herbs for a soothing ointment or healing drink are being prepared

This man's leg wound is being treated, while herbs for a soothing ointment or healing drink are being prepared

[Rieux] knew that … the plague bacillus never dies or vanishes entirely … it can remain dormant for dozens of years in furniture or clothing … it waits patiently in bedrooms, cellars, trunks, handkerchiefs and old papers, and … perhaps the day will come when, for the instruction or misfortune of mankind, the plague will rouse its rats and send them to die in some well-contented city.

The Plague, Albert Camus

The Black Death pandemic underscored the limitations of medieval medicine, where religious dogma often overshadowed scientific inquiry in explaining such cataclysmic events.

“Formerly, when religion was strong and science weak, men mistook magic for medicine; now, when science is strong and religion weak, men mistake medicine for magic.”

Thomas Szasz (15 April 1920 – 8 September 2012), Professor of Psychiatry and Author

FOR FURTHER READING

- Jenny Sutcliffe, Nancy Duin. A history of medicine from history to the year 2020. USA: Barnes and Noble Inc; 1992.

- Albert Lyons, R. Joseph Petrucelli II. Medicine An Illustrated History. New York: Henry N. Atnams Inc., Publishers; 1987.

- Roy Genders. A History of Scent. New York, USA: Hamilton Publishers; 1972.

- Albert Camus. Tr. Robin Buss. The Plague. Penguin Classics 2002.