When the bubonic plague descended upon London in 1665, panic spurred those who could afford it to flee to the countryside. Ironically, this exodus included many of the city’s established physicians. The Royal College of Physicians, the body governing medical licensing within a seven-mile radius of London, had no rules compelling its members to remain during outbreaks. As danger loomed, they were free to depart, leaving a void in healthcare for those who remained.

So, where did London’s working class turn in this desperate time? They sought help from the Quack Doctor, of course.

As the English surgeon Dale Ingram later noted, the absence of licensed physicians meant “recourse was had to chymists, quacks . . . every one was at liberty to prescribe what nostrum he pleased, and there was scarce a street in which some antidote was not sold, under some pompous title.” In times of crisis, the quack doctor often fills the gap left by established medical professionals.

The term “quack” itself derives from “quacksalver,” or “kwakzalver,” a Dutch term for someone selling nostrums – those early modern over-the-counter medications of questionable origin, taken without prescription and at the buyer’s risk. Quack doctors of this era were unregulated practitioners, often lacking the education or social standing to join physicians’ guilds or medical colleges. Instead, they set up shop in public spaces, from street corners to country fairs, loudly promoting their homemade concoctions – their booming voices leading to the very name “quack,” likened to the noisy calls of ducks or geese.

Oil painting of quack selling in a market

Oil painting of quack selling in a market

During London’s “Great Plague,” while established doctors retreated, the quack doctor remained. Some may have been genuinely caring healers, driven by duty to their communities. However, for others, it was a prime business opportunity. Pandemics and “plague years” are boom times for the quack doctor. This was true in 1665, centuries before during the Black Death, and again in 1918 during the global influenza pandemic. London’s plague year, in many ways, foreshadows our own recent experiences, reminding us that the historical quack doctor can still teach us valuable lessons today.

Lesson 1: Quack Doctors Thrive in a Vacuum of Legitimate Care

Abandoned by trained physicians, Londoners had limited choices beyond the remedies offered by peddlers and unlicensed chemists. While city authorities implemented some measures to control the plague—including quarantining infected houses and tracking deaths—these efforts were less effective than the public health strategies developed in Venice. Venice, as early as 1348, recognized the critical need for unified civic and medical leadership during public health emergencies.

Venice pioneered a plague-fighting health office, a precursor to modern public health infrastructure. This office integrated physicians and city government, and crucially, incorporated the work of various city workers—street sweepers, gravediggers, and census takers—to understand the plague’s spread and how to combat it. The term “quarantine” itself originates from the Italian “quaranta giorni,” or forty days, the isolation period for suspected plague cases and travelers on Venice’s Lazzaretto Vecchio island. While quack doctors and mountebanks still operated in Venice, a robust public health system helped keep the city relatively free of plague from the mid-1600s onwards. In contrast, plague outbreaks continued to plague other European cities, even into the 19th century. This highlights a critical lesson: the quack doctor flourishes where legitimate medical systems and public health infrastructure are weak or absent.

Lesson 2: Quack Doctors Exploit the Most Vulnerable

Throughout history, vulnerable populations have been prime targets for quack doctors and charlatans. Daniel Defoe, famed for Robinson Crusoe, also wrote a vivid account of the 1665 plague based on his family’s experiences. He described how nostrums were aggressively marketed to the poor through public notices and signs, promising miraculous cures in exchange for precious money:

“Infallible preventive pills against the plague.” “Neverfailing preservatives against the infection.” “Sovereign cordials against the corruption of the air.” “Exact regulations for the conduct of the body in case of an infection.” “Anti-pestilential pills.” “Incomparable drink against the plague, never found out before.” “An universal remedy for the plague.” “The only true plague water.” “The royal antidote against all kinds of infection”—the sheer volume of such promises was overwhelming.

Illustration of a quack doctor and poor family

Illustration of a quack doctor and poor family

Defoe recounted an especially egregious example: a quack doctor advertising “free advice” to the poor, conveniently omitting that the actual medicine would cost them dearly. While Defoe’s stories might be embellished, contemporary medical writings confirm that the poor were often seen as easy prey, not just by quack doctors. Physician Gideon Harvey, in his Discourse of the Plague, advised wealthy clients to avoid the poor, whom he considered more likely to carry disease and live in “nastier, and more putrid” environments. Harvey prescribed elaborate cures for the “rich,” while his advice for the “poor” largely consisted of purging and vomiting. Given such attitudes within the established medical profession, it’s understandable why London’s poor might turn to the seemingly accessible promises of the quack doctor.

Lesson 3: The Remedies of a Quack Doctor are Rarely Worth the Price

Patent medicines sold by the quack doctor came with significant risks. Ingredients were secret and unregulated. Plague remedies might contain hellebore, a toxic herb intended to induce sweating and expel sickness. Another common ingredient was theriac, an ancient concoction of garlic, vinegar, onions, rue, and viper flesh, believed to fight the plague’s “poison.”

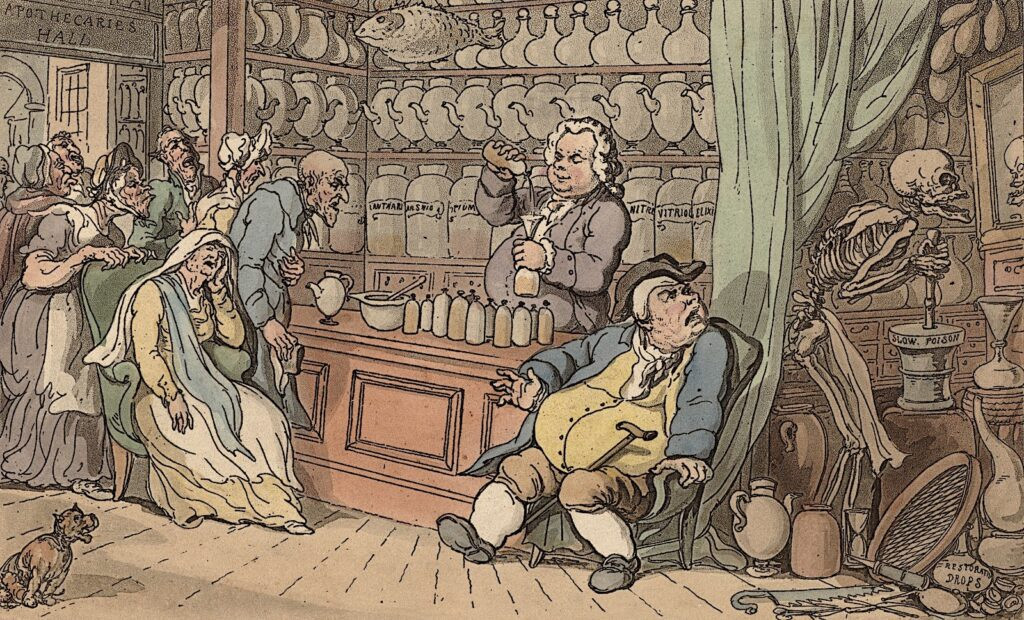

Satirical cartoon of apothecary

Satirical cartoon of apothecary

Other quack doctors recommended remedies like smoking tobacco, burning bonfires, or chewing wormwood and myrrh to dispel “bad air,” believed to cause disease. As Ingram observed about the 1665 plague, “I believe it would be better for us to have no physician, than to be . . . cheated with pretended medicines.” While Ingram, a licensed surgeon, might have been biased, even qualified doctors made errors, and their treatments could be as harmful as those of a quack doctor. Ingram himself described a “miracle” medicine from a prominent physician that, “cured the disease . . . by laying all those who took it quietly in the grave together,” revealing that even within the established medical field, deadly mistakes occurred.

During the 1918 influenza pandemic, quack doctors offered equally dubious cures. The flu’s high mortality rate and the medical establishment’s limited ability to combat it fueled sales of questionable remedies. Advertisements promoted products like Foley’s Honey and Tar Cough Remedy, Riley’s 24-Hour Flu Insurance, and Eucapine Salve, a toxic mix of eucalyptus and camphor intended to be snorted and swallowed for internal “sterilization.” Quinine-based remedies, like Hill’s Cascara Bromide Quinine, were also popular due to the mistaken belief that influenza and malaria, both causing fever, had similar origins. Even bloodletting, largely discredited by then, briefly resurged as desperate doctors and patients sought any possible cure. This historical pattern underscores that the remedies offered by a quack doctor, whether in the 17th or 20th century, were often ineffective and sometimes dangerous.

Lesson 4: “Quack Doctor” – The Label Itself Can Be Deceptive

The early modern medical establishment systematically excluded women, religious minorities, and other marginalized groups. Many skilled practitioners, excluded from formal institutions, trained through apprenticeships and worked independently. The London College of Physicians, which barred women, prosecuted at least 100 women between 1550 and 1650 for practicing medicine without licenses.

Color illustration of a woman in motley

Color illustration of a woman in motley

Despite facing persecution, these “medical outsiders” often provided essential care to their communities. During 16th-century bubonic plague outbreaks in Venice, Jewish physician David de Pomis treated patients of all faiths, despite laws prohibiting Christian patients from seeing Jewish doctors. After the plague subsided in 1589, de Pomis appealed to the Pope for a license to continue treating his Christian patients, emphasizing his dedication and skill. He also wrote a powerful defense of Jewish physicians against prevalent antisemitic attacks, which often falsely accused them of ritual killings of Christian patients (“blood libel”). De Pomis refuted these claims, stating that medicine was “an act of humanity,” a “sacramental bond” reminding us “all human beings are equally inserted into the chain of humanity.”

Interestingly, plague outbreaks themselves inadvertently broadened access to medical knowledge. Before the Black Death, most medical texts were in Latin, accessible only to scholars. The plague’s widespread impact led to a surge in medical texts in vernacular languages. These books targeted not just trained physicians but also barber-surgeons, parish priests, herbal healers, “wisewomen,” and even local lawmakers – anyone involved in combating the plague’s spread. The plague exposed the limitations of Europe’s medical networks, highlighting a shortage of trained physicians for such a large-scale disaster. This shift in medieval medical literature moved away from theoretical texts aimed at future physicians towards practical health advice – a “how-to” genre accessible to both professionals and those labeled as quack doctors. This historical context reveals that the label “quack doctor” was often used to marginalize those outside the established medical system, regardless of their skills or contributions.

Lesson 5: Even the Powerful Can Fall for a Quack Doctor

During London’s Great Plague, astrologer William Lilly profited handsomely from wealthy clients, offering astrological readings, health tonics, and advice on auspicious days for bloodletting. Quack doctors could even gain royal patronage. James Angier, a French quack doctor, convinced King Charles II’s Privy Council that burning brimstone could “sterilize” plague houses and prevent further infections. Similarly, William Read, a tailor-turned-mountebank eye surgeon, was knighted by Queen Anne and appointed royal oculist in 1705.

In a peculiar episode, John Wilmot, the Earl of Rochester, created the persona of “Dr. Alexander Bendo,” an Italian quack doctor, during a period of royal disfavor. In 1676, Rochester spent weeks advertising Bendo’s services across London, offering consultations. Despite Bendo’s clearly satirical nature—his handbills advertised fertility cures to prevent “leaving of Plentifull Estates, and Possessions to be inherited by Strangers”—he attracted wealthy and prominent clients eager to be fooled by an earl in disguise. This incident demonstrates that even wealth and status are no protection against the allure of the quack doctor.

Oil painting, portrait of a man in a wig

Oil painting, portrait of a man in a wig

Modern Quack Doctors and Enduring Lessons

It’s easy to draw parallels between historical plagues and the recent coronavirus pandemic, which has seen a resurgence of modern quack doctors. From January to August 2020, the FDA issued over 100 warning letters to companies making false claims about products “curing” or “protecting” against COVID-19. These ranged from essential oils and supplements to unproven diagnostic kits.

Even legitimate medicines can be misused and promoted with quackery. Chloroquine and hydroxychloroquine, antimalarial drugs, were touted as “game changers” against COVID-19 by prominent figures, including political leaders. However, clinical trials revealed these drugs, with potentially dangerous side effects, had little to no benefit for COVID-19 patients. Tragically, misinformation led to a couple poisoning themselves with aquarium cleaner mistakenly believing it to be chloroquine, with fatal consequences. Desperation, poverty, and lack of access to reliable healthcare continue to drive people to modern nostrums, just as they did centuries ago.

Conversely, similar to historical plague years, unlicensed practitioners and community volunteers stepped up during the pandemic to fill gaps in strained healthcare systems. In rural India, “quack doctors” or village healers played a vital role in implementing quarantines and disseminating information about hygiene in areas lacking healthcare infrastructure. In the United States, mutual aid networks, mask makers, food delivery drivers, and other essential workers contributed significantly to public health and safety.

Oil painting of early modern doctor chemist

Oil painting of early modern doctor chemist

While each pandemic is unique, history teaches us about our ongoing vulnerability to both disease and the quack doctor who emerges in its wake. Historically, medical authorities attempted to suppress “unlettered chemists, shifting and outcast pettifoggers . . . stage-players, pedlars” and “prattle-prattling barbers,” but never fully eradicated them.

Similarly, quack doctors persist today, now circulating misinformation online as readily as they once did on London’s noticeboards. Despite access to vast medical information, a significant portion of the world still lacks basic healthcare or faces financial barriers to treatment. This gap continues to be filled by dubious remedies, unregulated practitioners, and wishful thinking, perpetuating the cycle of quackery.

Perhaps the most effective way to combat the quack doctor is not through punitive measures, but through a more fundamental solution: eradicating poverty. By addressing this root cause, we might diminish the conditions in which the quack doctor thrives and ensure access to reliable healthcare for all. Without the plague of poverty, many quack doctors might indeed need to find a new profession.

Correction: An earlier version of this story misstated the century during which David de Pomis was active.