Jeff Glidewell’s neck pain had escalated to an agonizing point. The pinched nerve in his back sent waves of unbearable discomfort, making simple movements like turning his head or riding in a car feel like electric shocks surging through his body. At 54, Glidewell was already living on disability due to a previous accident a decade prior. As the pain intensified, neurosurgery became his only viable option. Living in suburban Dallas, he turned to Google, searching for a neurosurgeon nearby who accepted his Medicare Advantage insurance.

This search led him to Doctor Christopher Duntsch in the spring of 2013, a name that seemed promising at first glance.

Duntsch presented an impressive facade. His curriculum vitae boasted an MD and a PhD from a prestigious spinal surgery program. Online reviews on platforms like Healthgrades were filled with four- and five-star ratings. His Facebook page echoed similar praise, seemingly from satisfied patients. A video on “Best Docs Network” showcased a confident Doctor Christopher Duntsch in a white coat, interacting with a happy patient and appearing in a sterile operating room.

Unbeknownst to Glidewell, and hidden beneath this carefully constructed online persona, lay a terrifying reality. Becoming a patient of Doctor Christopher Duntsch was, in fact, to step into grave danger.

In the two years Doctor Christopher Duntsch had been practicing medicine in Dallas, he had performed surgeries on 37 individuals. A staggering 33 of these patients suffered significant injuries during or after their procedures, experiencing complications of an almost unheard-of severity. Some were left with permanent nerve damage. Others awoke from surgery paralyzed, unable to move their limbs or feel parts of their bodies. Tragically, two patients died in the hospital, including a 55-year-old schoolteacher undergoing what should have been a routine day surgery.

The healthcare system is designed with multiple layers of protection to safeguard patients from incompetent or dangerous doctors and to provide recourse when harm occurs. However, the case of Doctor Christopher Duntsch starkly reveals how these safeguards can fail, even in the most egregious circumstances.

Hospitals generate substantial revenue from neurosurgeons, making them highly valuable assets. This financial incentive allowed Doctor Christopher Duntsch to secure operating privileges at several Dallas-area hospitals. When his profound incompetence became undeniable, many of these institutions chose to avoid the legal complexities and negative publicity of outright firing him. Instead, they allowed him to resign quietly, preserving his reputation and enabling him to continue his disastrous practice elsewhere.

At least two hospitals that quietly let Doctor Christopher Duntsch go failed to report him to the National Practitioner Data Bank, a federal database intended to flag problematic practitioners and warn potential employers.

“It seems to be the custom and practice,” observed Kay Van Wey, a Dallas attorney who represented 14 of Duntsch’s victims in malpractice suits. “Kick the can down the road and protect yourself first, and protect the doctor second and make it be somebody else’s problem.”

It took over six months and a series of catastrophic surgeries before anyone reported Doctor Christopher Duntsch to the Texas Medical Board, the body responsible for licensing and disciplining physicians. Even then, nearly another year passed before the board initiated a full investigation, during which time Duntsch continued to operate and inflict harm.

When Duntsch’s patients attempted to sue him for medical malpractice, many faced significant obstacles in finding legal representation. Texas tort reform, enacted in 2003, had drastically reduced the potential financial compensation in such cases, making them less attractive to attorneys.

Doctor Christopher Duntsch declined to be interviewed for this article through his attorney. Representatives from several hospitals where he worked also either declined to comment or stated they could not comment due to management changes or hospital closures.

Ultimately, it was the criminal justice system, not the medical system, that brought a measure of accountability for Doctor Christopher Duntsch’s devastating malpractice.

In July 2015, Duntsch was arrested, and Dallas prosecutors charged him with multiple counts, including injury to an elderly person and assault, all stemming from his surgical procedures.

The case became a media sensation, both locally and nationally. D Magazine, a Dallas publication, featured a cover story in 2016 with the chilling headline “Dr. Death,” a moniker that quickly became synonymous with Doctor Christopher Duntsch.

In a landmark verdict, Doctor Christopher Duntsch was convicted and sentenced to life in prison, marking the first time a doctor in the United States received such a sentence for actions committed in the course of practicing medicine.

“The medical community system has a problem,” stated Assistant District Attorney Stephanie Martin at a press conference following the verdict. “But we were able to solve it in the criminal courthouse.”

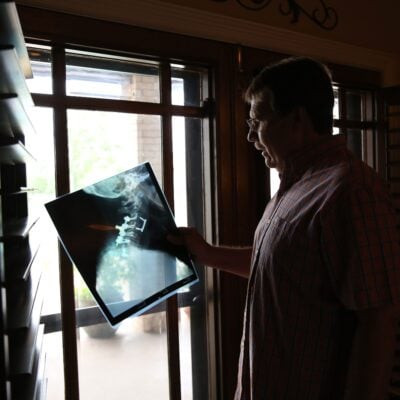

Jeff Glidewell holds the grim distinction of being the last patient Doctor Christopher Duntsch operated on before his medical license was finally suspended.

Jeff Glidewell, the final patient of the infamous Doctor Christopher Duntsch, recounts his surgery experience in 2013, highlighting the critical phone call he made to a judge in early 2015 that reignited the District Attorney’s investigation into the case. (Dylan Hollingsworth for ProPublica)

Jeff Glidewell, the final patient of the infamous Doctor Christopher Duntsch, recounts his surgery experience in 2013, highlighting the critical phone call he made to a judge in early 2015 that reignited the District Attorney’s investigation into the case. (Dylan Hollingsworth for ProPublica)

Medical experts who reviewed Glidewell’s case concluded that Doctor Christopher Duntsch mistakenly identified a neck muscle as a tumor and inexplicably abandoned the surgery midway through. Before doing so, he had cut into Glidewell’s vocal cords, punctured an artery, sliced a hole in his esophagus, and inexplicably stuffed a surgical sponge into the wound before sewing him up – sponge and all.

Glidewell spent four harrowing days in intensive care and endured months of painful rehabilitation to recover from the esophageal wound. Even today, he can only consume food in small portions and suffers from persistent nerve damage. “He still has numbness in his hand and in his arm,” explained his wife, Robin. “He basically can’t really feel things when he’s holding them in his fingers.”

Despite the severity and notoriety of the Duntsch case, neither Glidewell, the prosecutors, nor even Duntsch’s own defense attorneys believed it had served as a true wake-up call for the system responsible for policing doctors.

“Nothing has changed from when I picked Duntsch to do my surgery,” Glidewell lamented. “The public is still limited to the research they can do on a doctor.”

The Unconventional Path of Christopher Duntsch to Neurosurgery

Doctor Christopher Duntsch‘s journey into medicine was anything but conventional, perhaps mirroring his tendency to pursue improbable goals with unwavering focus.

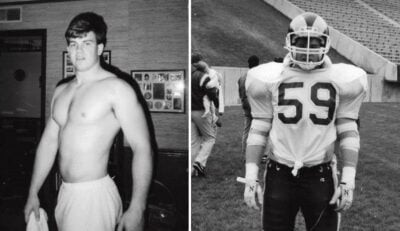

His first ambition was college football. Duntsch’s father had been a successful football player in Montana, and despite not being a naturally gifted athlete, Duntsch was determined to follow in his footsteps. He dedicated himself to relentless training and played linebacker on his high school team in Memphis, Tennessee. Classmates remember him as a force of sheer willpower.

Composite image showcasing Doctor Christopher Duntsch’s early ambition to play football before his medical career, illustrating his transition from athletic aspirations to neurosurgery, with a teammate’s quote highlighting Duntsch’s success through “sweat equity.” (Via Facebook)

Composite image showcasing Doctor Christopher Duntsch’s early ambition to play football before his medical career, illustrating his transition from athletic aspirations to neurosurgery, with a teammate’s quote highlighting Duntsch’s success through “sweat equity.” (Via Facebook)

“He had his goal, his sight on a goal and whatever it took to get there,” recalled a classmate who preferred to remain anonymous. “He wanted to go to college and play, and I can recall he was like 180 pounds and said, ‘I need to get to 220’ in order to be a linebacker at Colorado or Colorado State.”

He eventually enrolled at Millsaps College in Mississippi, which offered him financial aid. However, his ambition led him to seek a transfer to a Division I team. He set his sights on the Colorado State Rams during his sophomore year and successfully became a walk-on player. Chris Dozois, a fellow linebacker with the Rams, remembers Duntsch struggling with basic drills but persistently requesting to repeat them.

“He’d be, ‘Coach, I promise I can get this, let me do it again.’ He’d go through; he’d screw it up again,” Dozois recounted. “I gathered very quickly that everything that he had accomplished in sports had come with the sweat equity. When people said, ‘You weren’t going to be good enough,’ he outworked that and he made it happen.”

Homesickness led Duntsch to leave Colorado after a year, transferring to Memphis State University, now the University of Memphis. His hopes of playing football there were dashed as he tearfully confided to Dozois that his multiple transfers had cost him his eligibility.

It was at this point, Dozois recalled, that Doctor Christopher Duntsch declared his next ambitious goal: to become a doctor. And not just any doctor, but a neurosurgeon, specializing in operating on injured backs and necks.

From Stem Cell Research to Surgical Residency: The Making of a “Neurosurgeon”

After earning his undergraduate degree in 1995, Duntsch enrolled in the MD-PhD program at the University of Tennessee at Memphis College of Medicine, an ambitious undertaking aimed at achieving both a medical doctorate and a doctorate in philosophy.

As part of this program, he worked in a research lab, focusing on the origins of brain cancer and the potential applications of stem cells. Following the completion of his dual degrees in 2001 and 2002, it seemed for a time that Doctor Christopher Duntsch might forge a career in biotechnology rather than clinical practice.

During his surgical residency, Duntsch collaborated with two Russian scientists recruited by the University of Tennessee to explore the commercial potential of stem cells in treating back ailments. They patented a technology for obtaining and cultivating disc stem cells and, in 2008, launched a company called DiscGenics to develop and market these products. Notably, two of Duntsch’s supervisors from the university were among the initial investors.

Doctor Christopher Duntsch pictured on his first day as a neurosurgeon, a profession he pursued after ventures in biotechnology and stem cell research, despite underlying issues that would later surface. (Via Facebook)

Doctor Christopher Duntsch pictured on his first day as a neurosurgeon, a profession he pursued after ventures in biotechnology and stem cell research, despite underlying issues that would later surface. (Via Facebook)

While Doctor Christopher Duntsch appeared to be thriving professionally during these years, darker aspects of his personal life remained hidden beneath the surface.

Sworn testimony from 2014 by an ex-girlfriend of one of his close friends described a drug-fueled, all-night birthday celebration for Duntsch during his residency. Revelers reportedly consumed alcohol, cocaine, and pills. At dawn, Duntsch allegedly donned his white coat and proceeded to the hospital for his rounds.

“Most people, when they go binge all night long, they don’t function the next day to go to work,” she stated in her deposition. “After you’ve spent a night using cocaine, most people become paranoid and want to stay in the house. He was totally fine going to work.”

Rand Page, an early investor in DiscGenics, initially impressed by Duntsch’s presentation and business acumen, grew increasingly wary of his new business partner over time.

“We would meet in the mornings, and he would be mixing a vodka orange juice to start off the day,” Page recalled. On one occasion, stopping by Duntsch’s house to retrieve paperwork, Page opened a desk drawer and found a mirror with cocaine and a rolled-up dollar bill on top.

Ultimately, Doctor Christopher Duntsch was ousted from DiscGenics, and his partners and investors initiated legal action against him concerning financial matters and stock ownership. (Representatives from DiscGenics declined to be interviewed for this story.)

The University of Tennessee stated they could not comment on Duntsch, citing student record confidentiality. However, Dr. Frederick Boop, chief of neurosurgery at the hospital where Duntsch completed his residency, appears to have been aware of Duntsch’s substance abuse issues.

In a 2012 phone call recorded by a Texas doctor alarmed by Duntsch’s surgical errors and who contacted Boop, Boop acknowledged an anonymous complaint against Duntsch alleging drug use before seeing patients.

During this conversation, Boop indicated that university officials had requested Duntsch undergo a drug test, but he had evaded it, disappearing for several days. Upon his return, he was reportedly enrolled in a program for impaired physicians and placed under close supervision for the remainder of his surgical training, according to Boop. (An attorney for the University of Tennessee stated Boop would not respond to questions for this story.)

The extent of Duntsch’s actual surgical training remains unclear.

Following his arrest, the Dallas district attorney’s office subpoenaed records from every hospital listed on Duntsch’s CV, including his residency and subsequent one-year fellowship.

The Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education stipulates that a neurosurgery resident should perform approximately 1,000 operations during training. However, records gathered by the DA revealed that Doctor Christopher Duntsch had performed fewer than 100 operations by the time he completed his residency and fellowship.

Despite his earlier aspirations voiced to friends, Rand Page believes Duntsch’s primary focus was on business, not medicine.

“I don’t think his plan was ever to become a surgeon,” Page stated. When Duntsch was removed from DiscGenics, “I think the decision was made for him that he was going to have to enter into the medical community to support himself.”

The Downward Spiral Begins: Duntsch’s First Surgical Positions and Mounting Red Flags

Doctor Christopher Duntsch’s first position as a practicing physician was at the Minimally Invasive Spine Institute in Plano, an affluent Dallas suburb. He was hired in the summer of 2011, simultaneously gaining operating privileges at Baylor Regional Medical Center.

Baylor-Plano welcomed Duntsch with a substantial $600,000 advance. While representatives from the institute declined interviews, they provided an email detailing the glowing recommendations they received from Duntsch’s supervisors at the University of Tennessee medical school in Memphis.

“We were told Duntsch was one of the best and smartest neurosurgeons they ever trained, as they went on at length about his strengths,” the email stated. “When asked about Dr. Duntsch’s weaknesses or areas for improvement, the supervising physician communicated that the only weakness Duntsch had was that he took on too many tasks for one person.”

In 2010, Dr. Boop faxed a recommendation for Doctor Christopher Duntsch to Baylor-Plano, marking “good” or “excellent” in skill assessments and noting, “Chris is extremely bright and possibly the hardest working person I have ever met.” Another supervisor, Dr. Jon Robertson, a family friend of the Duntsches and an investor in DiscGenics, highlighted Duntsch’s “excellent work ethic” in his recommendation. (A University of Tennessee attorney stated Dr. Robertson could not respond to questions.)

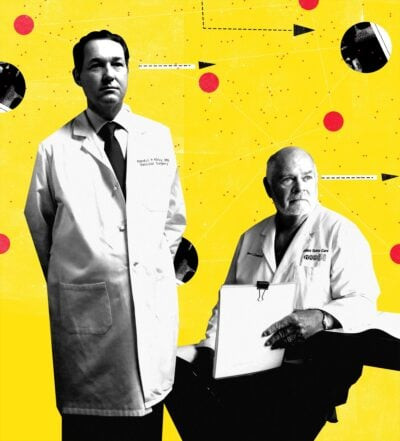

Dr. Randall Kirby, a vascular surgeon at Baylor-Plano, met Duntsch shortly after his arrival and found him to be arrogant and opinionated.

Dr. Randall Kirby, pictured on the left, and Dr. Robert Henderson, pictured on the right, are two physicians who played crucial roles in preventing Doctor Christopher Duntsch from continuing to operate on unsuspecting patients, driven by their concern for patient safety. (Nate Kitch, special to ProPublica)

Dr. Randall Kirby, pictured on the left, and Dr. Robert Henderson, pictured on the right, are two physicians who played crucial roles in preventing Doctor Christopher Duntsch from continuing to operate on unsuspecting patients, driven by their concern for patient safety. (Nate Kitch, special to ProPublica)

“I would see him maybe once a week at the scrub sinks or in the doctor’s lounge,” Kirby recounted. “He is among giants up there, and he was trying to tell me over and over again how most of the spine surgery here in Dallas was being done inappropriately and that he was going to clean this town up.”

Duntsch’s tenure at the spine institute was short-lived, lasting only a few months. However, his departure wasn’t due to patient complications but rather a dispute with other doctors regarding his professional responsibilities.

One weekend in September 2011, Kirby recounted, Duntsch was assigned to patient care but instead traveled to Las Vegas. Dr. Michael Rimlawi, a partner at the institute, “was notified by the administration that the patient wasn’t getting rounded on, and Dr. Rimlawi then dismissed Dr. Duntsch after that,” Kirby stated. (Dr. Rimlawi declined to comment for this story.)

Despite his dismissal from the spine institute, Doctor Christopher Duntsch retained his operating privileges at Baylor-Plano. On December 30, 2011, he performed surgery on Lee Passmore.

Passmore, an investigator with the Collin County Medical Examiner’s office, had previously undergone successful back surgery, but his pain had returned. His pain specialist, lacking a regular referral back surgeon, mentioned a recent lunch with a surgeon who “seemed like a guy that knew what he was talking about,” as Passmore testified in court.

Vascular surgeon Mark Hoyle assisted in the procedure. In subsequent testimony, Hoyle expressed alarm as Duntsch began cutting a ligament near the spinal cord, an area typically untouched in such surgeries. Passmore began bleeding profusely, obscuring the surgical field in blood. Hoyle testified that Duntsch not only misplaced hardware in Passmore’s spine but also stripped a screw, rendering it unmovable. At one point, Hoyle stated he either physically stopped Duntsch’s scalpel or blocked the incision to prevent further procedure continuation. Hoyle then left the operating room, vowing never to work with Duntsch again. (In response to a comment request, Hoyle indicated he was finished discussing Duntsch.)

Passmore did not respond to requests for comment for this story. He has testified to living with chronic pain and mobility issues as a result of Duntsch’s errors.

Escalating Surgical Disasters: Morguloff and Summers’ Tragedies

The next patient Doctor Christopher Duntsch operated on was Barry Morguloff.

Morguloff, a pool service company owner, had aggravated his back from years of physical labor in his father’s import business. His back pain had returned after a prior surgery, but his surgeon recommended exercise and weight loss over another procedure.

A pain specialist gave Morguloff Duntsch’s contact information.

“Everything that I read when we first got his card — outstanding reviews, people loved him. I read everything I could about this guy,” Morguloff recalled. He scheduled an appointment and was impressed by Duntsch’s confident demeanor.

“Phenomenal, great guy, loved him,” Morguloff said. Most importantly, “I was in pain and somebody, a neurosurgeon, said, ‘I can fix you.’”

His surgery, an anterior lumbar spinal fusion, took place on January 11, 2012. Vascular surgeon Kirby assisted Duntsch at the request of a head-and-neck surgeon also involved in the case. Kirby described it as a routine procedure.

“In the spectrum of what a neurosurgeon does for a living, doing an anterior lumbar fusion procedure’s probably the easiest thing that they do on a daily basis,” he stated.

However, Duntsch quickly encountered problems. Instead of a scalpel, he attempted to remove Morguloff’s problematic disc with a grabbing instrument, risking spinal damage. Kirby stated he argued with Duntsch, even offering to take over, but Duntsch insisted he knew what he was doing. Kirby then left the operating room.

Barry Morguloff, a victim of Doctor Christopher Duntsch’s surgical errors during what was supposed to be a routine procedure, now faces lasting physical damage affecting his mobility, with a progressive loss of function on the left side of his body over time. (Dylan Hollingsworth for ProPublica)

Barry Morguloff, a victim of Doctor Christopher Duntsch’s surgical errors during what was supposed to be a routine procedure, now faces lasting physical damage affecting his mobility, with a progressive loss of function on the left side of his body over time. (Dylan Hollingsworth for ProPublica)

Morguloff awoke in excruciating pain.

His previous surgeon testified at Duntsch’s trial that the procedure had left bone fragments in Morguloff’s spinal canal. Despite subsequent repair surgeries, Morguloff now relies on a cane to walk. His condition is expected to worsen as scar tissue accumulates, further limiting his mobility and increasing his pain, potentially leading to wheelchair dependence.

“As time goes on, the scar tissue and everything builds up, and I lose more and more function of that left side,” he explained. “I do my best to stay active. But some days I just can’t get moving. The pain is continuous.”

Soon after Morguloff’s surgery, Doctor Christopher Duntsch took on another patient, who was also a long-time friend, Jerry Summers.

Summers had played football with Duntsch in high school and assisted in logistics at his research lab during his residency. When Duntsch accepted the Dallas job, he asked Summers to move with him and help set up his practice. They shared a luxury high-rise apartment while Duntsch searched for a house.

In a deposition, Summers stated he asked Duntsch to operate on him due to chronic pain from a high school football injury, exacerbated by a car accident. However, following the February 2012 surgery, Summers was unable to move from the neck down.

Medical experts reviewing the case determined that Duntsch had damaged Summers’ vertebral artery, causing near-uncontrollable bleeding. To stem the hemorrhage, Duntsch packed the area with excessive anticoagulant, compressing Summers’ spine.

For days following the surgery, Summers remained in the ICU, sinking into severe depression. “Jerry was calm with Chris,” recalled Jennifer Miller, Summers’ girlfriend at the time, “but all Jerry would say to me is: ‘I want to die. Kill me. Kill me. I want to die.’”

One morning, Summers began yelling, telling nurses that he and Duntsch had spent the night before the surgery using cocaine. In reality, the night before surgery, Summers and Miller had dined at a local restaurant and watched a basketball game at the bar.

In his 2017 deposition, Summers admitted to fabricating the pre-surgery cocaine use, driven by feelings of abandonment by Duntsch, both as his surgeon and friend.

“I was just really mad and hollering and wanting him to be there,” Summers explained. “And so I made a statement that was not something that was necessarily true. … The statement was only made so that he might hear it and go, ‘Let me get my ass down there.’”

Baylor officials took Summers’ accusation seriously, ordering Doctor Christopher Duntsch to undergo a drug test. Similar to his behavior at the University of Tennessee, he initially stalled, claiming he got lost en route to the lab. He passed a subsequent psychological evaluation and, after a three-week suspension, was permitted to resume operating, but with restrictions to minor procedures.

The Tragic Case of Kellie Martin and Baylor-Plano’s Failure to Report

Doctor Christopher Duntsch’s first patient after his return was Kellie Martin, an elementary school teacher who suffered a compressed nerve from a fall while retrieving Christmas decorations. During her surgery, medical records indicate Martin’s blood pressure inexplicably plummeted.

Upon regaining consciousness, nurses reported Martin became agitated, slapping and clawing at her legs, which had become mottled and discolored. She was sedated due to her agitation but never regained consciousness. An autopsy later revealed that Duntsch had severed a major vessel in her spinal cord, leading to fatal blood loss within hours.

Baylor-Plano again ordered Doctor Christopher Duntsch to take a drug test. The initial screening was diluted with tap water, but a subsequent test came back clean. Hospital administrators also conducted a comprehensive review of Duntsch’s cases, leading to the determination that his time at the facility was over.

However, crucially, they did not terminate him outright. Instead, he resigned on April 20, 2012, with a lawyer-negotiated letter stating, “All areas of concern with regard to Christopher D. Duntsch have been closed. As of this date, there have been no summary or administrative restrictions or suspension of Duntsch’s medical staff membership or clinical privileges during the time he has practiced at Baylor Regional Medical Center at Plano.”

Because Duntsch’s departure was technically voluntary and his leave was under 31 days, Baylor-Plano was not obligated to report him to the National Practitioner Data Bank.

Established in 1990, the databank tracks malpractice payouts and disciplinary actions against doctors, including terminations, Medicare exclusions, suspensions, and license revocations.

This information is not publicly accessible or available to other doctors, but hospital administrators are granted access and are expected to utilize it to prevent problematic doctors from concealing their pasts by moving between states or hospitals. Robert Oshel, a patient safety advocate and former databank associate director, explains that hospitals are required to check all applicants for clinical privileges and biennially for all privileged clinicians.

However, many hospitals are hesitant to file reports with the databank, fearing potential harm to doctors’ career prospects or even triggering lawsuits.

“What happens sometimes is that doctors are allowed to resign in lieu of discipline so that the hospital can protect its perceived legal liability from the doctor,” explained Van Wey, the Dallas trial lawyer. “If Dr. Duntsch was unable to get privileges at other hospitals, theoretically Dr. Duntsch could have sued Baylor and said: ‘Look, I could be making $2 million a year here. … You owe me $2 million for the rest of my life.’”

According to a Public Citizen report, approximately half of U.S. hospitals had never reported a doctor to the databank by 2009. A more recent analysis indicated minimal change, according to Dr. Sid Wolfe of Public Citizen’s Health Research Group.

Despite the concerning pattern of issues at Baylor-Plano, Doctor Christopher Duntsch was also not reported to the Texas Medical Board, the state’s primary physician disciplinary body. While medical boards often operate slowly, hospital-provided documentation justifying a doctor’s dismissal can enable boards to act swiftly to protect patients from imminent danger.

“Had Baylor’s action been reported appropriately, I would anticipate the board would have met within days to have an immediate suspension,” stated Dr. Allan Shulkin, a Dallas pulmonologist who served on the medical board in 2012.

While an investigation would still be necessary, Duntsch would have been prevented from operating during its duration, Shulkin emphasized, expressing visible anger at Baylor-Plano’s reporting failure. “What’s the worst that can happen, a lawsuit?” he questioned. “Come on. These are people dying, and we’re stopping because you’re afraid of a lawsuit?”

Two years after Duntsch’s departure, Baylor-Plano’s decision not to report its review or findings led to a state health authority investigation. The hospital received a violation and a $100,000 fine in December 2014, but this citation and penalty were rescinded a year later. The Texas Health and Human Services Commission cited confidentiality as the reason for not explaining the reversal.

Hospital officials declined interview requests, providing a written statement instead.

“Our primary concern, as always, is with patients,” it read. “Out of respect for the patients and families involved, and the privileged nature of a number of details, we must continue to limit our comments. There is nothing more important to us than serving our community through high-quality, trusted healthcare.”

Dallas Medical Center and the Catastrophes of Floella Brown and Mary Efurd

Doctor Christopher Duntsch’s next position was at Dallas Medical Center, located just outside Dallas in Farmers Branch. Baylor-Plano may have assumed future employers would contact them for confidential information, but Dallas Medical Center granted Duntsch temporary privileges while reference checks were still underway.

On July 24, 2012, Duntsch operated on Floella Brown, 64, a banker nearing retirement who sought cervical spine surgery for neck and shoulder pain.

Approximately 30 minutes into Brown’s surgery, Duntsch began complaining of visibility issues due to excessive bleeding.

“He was saying: ‘There’s so much blood I can’t see. I can’t see this,’” recalled Kyle Kissinger, an operating room nurse. He repeatedly instructed the scrub tech to “’suck more, suck more. Get that blood out of there. I can’t see.’ That’s really concerning to me because, not only that he can’t do it correctly when he can’t see that but, why is it still bleeding?”

Brown bled so profusely that blood saturated the surgical drapes and dripped onto the floor, requiring nursing staff to use towels to absorb it.

While Brown initially seemed well after surgery, she lost consciousness early the next morning due to increasing intracranial pressure.

The same morning, with Brown in critical condition, Doctor Christopher Duntsch proceeded with another surgery on Mary Efurd, an active 71-year-old seeking relief from back pain hindering her treadmill use.

Duntsch arrived approximately 45 minutes late for Efurd’s scheduled surgery, according to Kissinger. Kissinger noticed a hole in Duntsch’s scrubs, “It’s on the butt cheek of his scrubs. He didn’t wear underwear. That’s why it really shined down to me,” Kissinger stated. He realized he had seen the same hole for three consecutive days, suggesting Duntsch hadn’t changed his scrubs all week. Kissinger also observed Duntsch’s pinpoint pupils and infrequent blinking.

Upon arrival, staff informed Duntsch of Brown’s critical condition.

Shortly after beginning Efurd’s surgery, Duntsch instructed Kissinger to inform the front desk he would perform a craniotomy on Brown to relieve brain pressure. However, Dallas Medical Center lacked the facilities and equipment for craniotomies.

During Efurd’s surgery, Duntsch reportedly argued with Kissinger and later with supervisors, insisting on a craniotomy for Brown, according to court testimony. Operating room staff questioned the placement of hardware in Efurd, noting Duntsch’s repeated drilling and screw adjustments.

Ultimately, Duntsch did not perform a craniotomy on Brown. She was transferred to another hospital but never regained consciousness. Her family made the difficult decision to withdraw life support days later. A neurosurgeon reviewing her case determined Duntsch had pierced and blocked her vertebral artery with a misplaced screw, also misdiagnosing her pain source and operating in the wrong location.

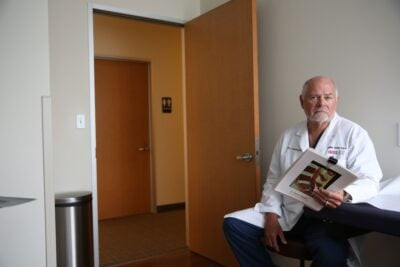

The day after her surgery, Efurd awoke in severe pain, unable to move or feel her lower extremities. Hospital administrators called Dr. Robert Henderson, a Dallas spine surgeon, to attempt to repair the damage.

Upon reviewing Efurd’s postoperative X-rays, Henderson’s initial reaction was, “I’m really thinking that some kind of travesty occurred.” This impression intensified upon reopening Efurd’s incisions the next day. “It was as if he knew everything to do,” Henderson said of Duntsch, “and then he’d done virtually everything wrong.”

Henderson found three holes in Efurd’s spinal column from Duntsch’s failed screw insertions. One screw was driven directly into her spinal canal, impaling nerves controlling her leg and bladder. Henderson removed bone fragments and discovered one of Efurd’s nerve roots completely missing, inexplicably amputated by Duntsch.

The surgical damage was so severe that Henderson initially suspected Duntsch was an impostor. Despite Henderson’s corrective efforts, Efurd never regained mobility and now uses a wheelchair. (In an email, Efurd indicated that discussing her experience further would negatively impact her health.)

By week’s end, hospital administrators informed Doctor Christopher Duntsch he could no longer operate at Dallas Medical Center. However, as with Baylor-Plano, Duntsch was allowed to resign, and the hospital did not report him to the National Practitioner Data Bank. Dallas Medical Center officials stated that current management could not comment on Duntsch’s tenure or departure circumstances due to administrative changes.

Duntsch’s surgical practice, however, was far from over. His Dallas career was only at its midpoint.

Medical Board Intervention and the Final Act at University General

Following Doctor Christopher Duntsch’s disastrous period at Dallas Medical Center, he was finally reported to the Texas Medical Board. The initial report came from Dr. Shulkin, the Dallas physician and board member, alerted to the surgeries on Efurd and Brown. Other doctors also began filing complaints.

“Once I heard about those cases, I called the medical board,” stated Kirby, the vascular surgeon present during Morguloff’s surgery. “I said: ‘Listen, we’ve had egregious results at Baylor-Plano. He was not reported to the databank. We’ve had egregious results at Dallas Medical Center. He’s got to be stopped.’”

After being called in to assist Efurd, Henderson also made it his mission to prevent Duntsch from operating again. He contacted Boop at the University of Tennessee to inquire about Duntsch’s training and spoke with officials at Baylor-Plano hospital. He also reported to the state medical board.

After a couple of months passed without further incidents, Henderson and Kirby assumed Duntsch’s actions had finally caught up with him.

Then, in December 2012, Kirby was asked to assist Jacqueline Troy, a patient with a severe infection. (The Troy family declined to comment for this story.) Troy was being transferred to a Dallas hospital from a Frisco surgery center following neck surgery where the surgeon had damaged her vocal cords and an artery. Upon learning the details, Kirby inquired about the surgeon’s identity: “Is it a guy named Christopher Duntsch?”

It was.

Duntsch had secured a position at Legacy Surgery Center, an outpatient clinic. (The clinic’s ownership has changed, and the new owners declined to comment.)

Shortly after Troy’s surgery, Doctor Christopher Duntsch was finally reported to the National Practitioner Data Bank, not by previous employers, but by Methodist Hospital in McKinney, which had denied him privileges six months prior due to “substandard or inadequate care” at Baylor-Plano. (Methodist McKinney declined to comment.) The report was dated January 15, 2013.

Even with the databank report, Kirby was astonished to learn Duntsch had gained privileges at yet another hospital. In May 2013, he received an invitation to a “Meet Our New Specialist” dinner hosted by University General Hospital to celebrate the arrival of their new neurosurgeon: Doctor Christopher Duntsch.

“I called down there and raised holy hell,” Kirby recalled.

Dr. Kirby, pictured in his Dallas office, a vascular surgeon who witnessed one of Doctor Christopher Duntsch’s surgeries, dedicated himself to preventing Duntsch from operating again, driven by patient safety concerns. (Dylan Hollingsworth for ProPublica)

Dr. Kirby, pictured in his Dallas office, a vascular surgeon who witnessed one of Doctor Christopher Duntsch’s surgeries, dedicated himself to preventing Duntsch from operating again, driven by patient safety concerns. (Dylan Hollingsworth for ProPublica)

University General, formerly South Hampton Community Hospital, had a history of financial instability, including bankruptcies and a CEO imprisoned for healthcare fraud. Acquired in 2012 by a Houston-based company for $30 million, University General was one of only three hospitals serving a large, underserved area of southern Dallas. The community hoped for its revitalization.

The hospital has since closed, and administrators from that period did not respond to inquiries regarding Duntsch’s hiring.

Economic factors likely played a significant role. According to Merritt Hawkins, a healthcare analysis firm, the average neurosurgeon generates $2.4 million annually for a hospital.

“That’s a dream for a hospital administrator,” Kirby noted.

This revenue potential translates to near-guaranteed employment for doctors with Duntsch’s credentials, according to Dallas neurosurgeon Dr. Martin Lazar.

“I don’t think it’s because of our charm,” Lazar quipped. “We are like a cash cow.”

It was at University General that Glidewell underwent neck surgery, completely unaware of Duntsch’s two-year history of surgical catastrophes.

Glidewell’s back problems began nearly a decade earlier in a motorcycle accident. After rehabilitation, he attempted to return to his air conditioning systems job but was forced to stop due to persistent pain. His initial meeting with Doctor Christopher Duntsch left him optimistic and hopeful.

“I was actually so happy with the way it went that I called my wife and my mother and said, ‘I think I found somebody on my insurance that’s gonna fix my neck,’” he recounted.

The day of surgery began with an ominous sign. “We pulled out of the driveway, and soon as we started going forward down the street, a black cat ran across the front of the car,” Glidewell recalled. “I said, ‘Oh, Lord, this is not good.’ We turned the corner, and when we got on the first county road, and another one. Turning into the hospital, another one.”

Jeff Glidewell’s recovery journey after Doctor Christopher Duntsch’s surgery involved four days in intensive care and months of rehabilitation, with images depicting Glidewell, one portrait and one photo of him holding an iPad showing a picture from the day he returned home after months in the hospital, illustrating his long road to recovery. (Dylan Hollingsworth for ProPublica)

Jeff Glidewell’s recovery journey after Doctor Christopher Duntsch’s surgery involved four days in intensive care and months of rehabilitation, with images depicting Glidewell, one portrait and one photo of him holding an iPad showing a picture from the day he returned home after months in the hospital, illustrating his long road to recovery. (Dylan Hollingsworth for ProPublica)

Three black cats en route to the hospital. “I said, ‘We need to just turn around and go home.’”

At the hospital, Glidewell and his wife waited for hours. Doctor Christopher Duntsch finally arrived in a cab, three hours late. “He had on jeans that were frayed at the bottom,” Glidewell described. “He didn’t look like he was ready for a surgery.”

Reluctantly, Glidewell proceeded. Hours later, Duntsch informed Glidewell’s wife he had discovered a tumor in Glidewell’s neck and had to abort the procedure.

“I was devastated, crying,” Robin Glidewell recalled. She went to the recovery room to see her husband. “Immediately, Jeff was: ‘Where is the doctor? I can’t move my arm or my leg.’ He was having trouble even talking and said, ‘Something’s wrong, something’s wrong.’”

There was no tumor. A review determined Duntsch had made a series of errors, mistaking neck muscle for a growth.

University General’s owner contacted Kirby upon learning of Glidewell’s case to mitigate the damage.

“I, with reluctance, went down there and met the Glidewell family and took care of him,” Kirby stated. Glidewell was transferred to another hospital for care, where he remained for months due to spiking fevers and complications.

“This was not an operation that was performed,” Kirby concluded. “This was attempted murder.”

Revocation, Criminal Charges, and a Life Sentence for Dr. Death

By the time Doctor Christopher Duntsch operated on Glidewell, the Texas Medical Board had been investigating him for approximately 10 months.

Frustrated by the board’s slow progress, Henderson had contacted the lead investigator six months prior, pleading for expedited intervention. In a recorded call, Henderson urged, “This is a bad, bad guy, and he needs to be put on the fast track if there’s such a thing.” The investigator responded that while she wished they could suspend his license during the investigation, the board’s attorneys were hesitant.

Kirby sent a strongly worded five-page letter to the board on June 23, 2013, prompted by Glidewell’s case. “Let me be blunt,” it stated. “Christopher Duntsch, Texas Medical Board license number N8183, is an impaired physician, a sociopath, and must be stopped from practicing medicine.” Robin Glidewell also sent a letter detailing her husband’s experience.

Brett Shipp, a reporter from Dallas’ ABC affiliate, had received tips about the board’s slow investigation from patient contacts and a malpractice attorney. “Very shortly after I contacted them,” Shipp stated, “they suspended his license.”

On June 26, Duntsch was ordered to cease operating. Dr. Irvin Zeitler, then head of the medical board, explained the investigation’s duration, stating “it’s not uncommon for there to be complications in neurosurgery.”

The board also found it difficult to believe a recently trained surgeon could be so inept.

“So none of us rushed to judgment,” Zeitler explained. “That’s not fair, and in the long run, it can come back to be incorrect. To suspend a physician’s license, there has to be a pattern of patient injury. So that was, ultimately that’s what happened. But it took until June of 2013 to get that established.”

Dr. Henderson, pictured, was called in to repair surgical damage inflicted on a patient by Doctor Christopher Duntsch, and upon witnessing the extent of the harm, he dedicated himself to preventing Duntsch from operating again to protect future patients. (Dylan Hollingsworth for ProPublica)

Dr. Henderson, pictured, was called in to repair surgical damage inflicted on a patient by Doctor Christopher Duntsch, and upon witnessing the extent of the harm, he dedicated himself to preventing Duntsch from operating again to protect future patients. (Dylan Hollingsworth for ProPublica)

Even after the board’s action, those who had worked to stop Doctor Christopher Duntsch feared it might not be the end of his medical career.

“I was terrified of that term, ‘suspended,’” Henderson admitted. “I mean, that indicates that he might get it back at some point in time, and I was already aware of the fact of how glib Dr. Duntsch was, and how disarming he was, and how friendly and intelligent he appeared whenever he introduced himself to people that he wanted to impress. I was concerned that he would do the same thing in getting his license back whether it was six months later, a year later, two years later.”

Kirby, Henderson, and another doctor decided to approach the district attorney, believing Duntsch’s malpractice was so egregious it constituted criminal behavior. Their initial meeting with an assistant DA yielded little progress.

On December 6, 2013, the medical board permanently revoked Duntsch’s license.

He left Texas, moving to Colorado to live with his parents and filing for bankruptcy, claiming approximately $1 million in debt. His life spiraled downwards. In January 2014, he was arrested for DUI in southern Denver after being found driving erratically with flat tires and an open alcohol container. He was sent to a detox facility.

Despite living in Colorado, he continued to visit Dallas to see his two sons. His first son was born during his time at Baylor-Plano, and his girlfriend, Wendy Young, had a second son in September 2014.

The following spring, police were called to a Dallas bank after reports of a man with blood on his hands and face banging on the doors. It was Duntsch, rambling about his family being in danger, wearing blood-stained black scrubs. He was taken to a psychiatric hospital.

In April, Duntsch went to a Dallas Walmart to collect money wired by his father. According to a police report, he filled a shopping cart with $887 worth of merchandise, including watches, sunglasses, ties, electronics, cologne, and clothing. He concealed items in bags and put on a new pair of trousers in the dressing room before attempting to leave the store without paying. He was arrested for shoplifting.

Doctor Christopher Duntsch’s mugshot following his arrest for shoplifting, marking a personal and professional downfall after the revocation of his medical license and mounting legal and personal troubles. (Dallas County Sheriff)

Doctor Christopher Duntsch’s mugshot following his arrest for shoplifting, marking a personal and professional downfall after the revocation of his medical license and mounting legal and personal troubles. (Dallas County Sheriff)

By this time, reporters were closely following the unfolding Duntsch saga. In May 2015, the Texas Observer published an article titled “‘Sociopath’ Surgeon Duntsch Arrested for Shoplifting Pants.” In the article’s comment section, Duntsch posted lengthy diatribes against those he believed had conspired against him, a cybermanifesto exceeding 80 printed pages.

In one comment directed at Kirby, he wrote, “You use the word without explanation impaired physician and sociopath. Since I am going to sue you or [sic] libel and slander of a criminal nature, this might be a good point to defend this comment.” He even described Morguloff’s surgery as “a perfect success.”

Kirby forwarded these comments to the district attorney’s office. Around the same time, a judge familiar with Glidewell’s case also brought it to the DA’s attention.

Prosecutors re-examined the case. Assistant District Attorney Michelle Shughart found it particularly compelling. In her 13 years with the Dallas DA’s office, she had prosecuted drug dealers and robbers but never a doctor. “I went and started doing my own research,” she stated. “I just ended up taking over the case.”

A primary challenge was the unprecedented nature of the case.

“We did a lot of research to see if we could find anyone else who had done any cases like this, any other doctors who had been prosecuted for what they had actually done during the surgery,” Shughart explained. “We couldn’t find anyone.”

As prosecutors contacted Duntsch’s patients and their families, they grappled with determining appropriate criminal charges. They ultimately settled on five counts of aggravated assault related to four patients, including Brown and Glidewell, and one count of injury to an elderly person, due to Efurd’s age.

In Texas, injury to an elderly person carried a potential life sentence, but prosecutors faced a statute of limitations deadline in Efurd’s case.

“We had about four months left before we were going to run out on the statute of limitations” on Efurd’s case, Shughart stated. “I spent those four months just digging as hard as I possibly could, trying to gather as much information as I could. And by the time we got down to that July, I had overwhelming evidence to indict him.”

Duntsch was arrested on July 21, 2015.

For some patients, the criminal case offered a final opportunity for justice unavailable through civil courts.

Texas’s cap on medical malpractice damages, limiting non-economic damages in most cases to $250,000, had significantly reduced lawsuit filings and payouts.

Successful malpractice suits often relied on economic damages, such as lost earnings, which were uncapped in non-death cases. However, many of Duntsch’s patients were already disabled, elderly, or had lower incomes, making economic damages less substantial. Despite clear cases and irreversible injuries, several patients struggled to find legal representation.

“It is not worth an attorney’s time and energy to take on a malpractice case in the state of Texas,” Morguloff explained.

Ultimately, at least 19 of Duntsch’s patients or their families reached settlements, with 14 represented by Van Wey, who admitted taking them on more out of moral outrage than financial gain.

Morguloff, frequently turned down by attorneys, was surprised when Mike Lyons took his case. He received a confidential settlement but stated, “It wasn’t much.” He found greater satisfaction in the criminal case.

“To get this guy off the streets so nobody else got hurt again was important,” he said. “The public needed to know that there was a monster out there.”

Duntsch’s trial began on February 2, 2017, focusing on the charge of injuring an elderly person, related to Mary Efurd.

Efurd testified, but prosecutors, to demonstrate a pattern of behavior, presented a long line of Duntsch’s other patients and their relatives, over defense objections.

“You had people in walkers. You had people on crutches. You had people that could barely move. You had people that had lost loved ones,” Robbie McClung, Duntsch’s lead defense attorney, stated. “You had all sorts of things that had gone wrong. Before we even get to Mary Efurd, you can see that it’s just … it’s going downhill. I mean, it’s going downhill fast.”

A screenshot of Doctor Christopher Duntsch during a deposition, capturing a moment in the legal proceedings against him, showcasing his demeanor and involvement in the case. (District attorney’s office)

A screenshot of Doctor Christopher Duntsch during a deposition, capturing a moment in the legal proceedings against him, showcasing his demeanor and involvement in the case. (District attorney’s office)

Doctor Christopher Duntsch maintained remarkable composure, seemingly convinced of his competence as a surgeon.

“I always thought when I looked at him, even when he was in his jail clothes, he exuded a confidence,” Richard Franklin, another defense team member, observed. “And I could certainly understand why patients would trust him.”

However, as Dr. Lazar and other experts detailed Duntsch’s surgical errors for the jury, his demeanor visibly changed. His confidence seemed to evaporate.

“I think that he thought he was doing pretty good,” Franklin speculated. “Really and truly, in his own mind. Until he actually heard from those experts up there.”

A key prosecution witness was Kimberly Morgan, Duntsch’s surgical assistant from August 2011 to March 2012 and former girlfriend. Morgan described Duntsch’s volatile nature, oscillating between kindness and care towards patients and anger and confrontation behind closed doors.

Prosecutors had Morgan read excerpts from a disturbing email Doctor Christopher Duntsch sent her in the early hours of December 11, 2011, weeks before his first surgical disaster on Passmore at Baylor-Plano.

The email’s subject line was “Occam’s Razor.” Amidst profanity-laden rambling, Morgan read the most chilling passage:

“Unfortunately, you cannot understand that I am building an empire and I am so far outside the box that the Earth is small and the sun is bright,” Duntsch wrote. “I am ready to leave the love and kindness and goodness and patience that I mix with everything else that I am and become a cold blooded killer.”

The jury deliberated for only hours before finding Duntsch guilty of knowingly injuring Efurd. He received a life sentence and is currently incarcerated in Huntsville, Texas. His attorney filed an appeal in September, arguing that testimony regarding cases other than Efurd’s and Morgan’s email unfairly prejudiced the jury.

In February, the author visited Jerry Summers, Duntsch’s former football teammate and patient, in his Memphis apartment.

Summers remains paralyzed from the neck down, requiring 24-hour care. He sat in his power wheelchair as he discussed Duntsch, appearing resigned to his condition, his friend’s role, and the systemic failures that allow dangerous doctors to continue practicing. He stated he tries to avoid thinking about Dallas.

When asked why he trusted Duntsch as his doctor, Summers could not articulate a clear reason, gazing out the window in silence.

He knew his friend struggled with basic tasks like driving, he explained, but he simply assumed Duntsch had received adequate training in neurosurgery.

Correction, July 17, 2021: This story originally incorrectly stated how Christopher Duntsch’s time at Millsaps College was subsidized. He received financial aid, not a football scholarship.